That is the big question, after all, isn’t it? Rye is America’s oldest style of whiskey. It was the most valuable and the most desirable American-made whiskey on the market before Prohibition, but it clearly does not hold the same place in America’s drinking culture anymore. What happened? The answer is complicated, but worth exploring.

The near disappearance of rye whiskey from the American whiskey market was, in a nutshell, due to Prohibition. (The prelude to Prohibition is another discussion entirely.) To be clear, I don’t mean the morally driven quest for temperance that began a hundred years before politicians began using prohibition as a wedge issue to win votes. I mean that the literal act of passing the 18th amendment was the beginning of the end for rye whiskey. All the following points I’ll make on what sealed its fate would be moot if the 18th amendment had never passed. However, our nation’s Great Experiment did take place, and for 13 years, 10 months, nineteen days, seventeen hours, and 32 ½ minutes, Americans lost the freedom to buy the drink of their choice. The history of the spirits industry has since been written by the survivors of Prohibition, but we should endeavor to understand the events and circumstances that brought us into the present. How did we all end up drinking bourbon instead of rye? Let’s explore 8 major reasons:

1. It was expensive to make rye whiskey. Small grain size, heated warehouses, longer fermentation times, longer growing season.

2. PA distilleries were not allowed to form corporations until 1901. Pennsylvania’s distilling company owners established their headquarters out of state.

3. Pennsylvania’s rye whiskey producers doubted that Prohibition could ever become a reality.

4. The control of concentration warehouses was key in determining who controlled whiskey stocks.

5. Post-Prohibition laws regulated against a resurgence in rye whiskey producers.

a. Floor tax and the creation of state stores

b. Government sanctioned glass bottle monopoly (read about this HERE)

c. Roosevelt mandated that distilleries must be fully functional by December 5, 1933 and anyone unable to reach production status by then could not go into production.

6. The loss of generational expertise in making rye whiskey was devastating.

7. Distilleries and equipment had all been dismantled and sold off.

8. The success of rye whiskey, unfortunately, led to its failure. The Whiskey Trust’s failure to take over Pennsylvania’s distilleries meant that they did not come under the protection of the “Big Four” after Prohibition.

1. Rye Whiskey Was Expensive to Make

There are several simple explanations for why pure rye whiskey was (and still is) more expensive to make. First, and most obviously, was the fact that it was made from cereal rye grain. Not only was rye more expensive for distillers to buy by the bushel, a lot more rye (bulk) was required to make the same amount of whiskey. Why is this? The starchy endosperm of a rye berry is significantly smaller than that of a kernel of corn. The larger a seed’s endosperm, the more starch or carbohydrates it is storing. The more starch a seed contains, the more alcohol (or whiskey) can be coaxed from it. Well, in truth, the more starch a seed contains, the more sugars can be coaxed from the grain when cooking those starches down in a mash cooker. Yeasts, those marvelous single celled organisms that are responsible for making the world’s consumable ethanol, cannot “ingest” complex carbohydrates. So, distillers must carefully cook or “mash” their grain to break down the grain’s carbohydrates into simple sugars which can now be “digested” by the distiller’s preferred yeast. These “wee cavorting beasties” turn the distiller’s cooked mash into an alcoholic broth or distiller’s beer. Now, just for argument’s sake, if a rye berry contained half the carbohydrates of a kernel of corn, you would need twice as much rye to produce the same amount of alcohol. This is also why many distillers would add corn to their recipe. It had more carbohydrates which made alcohol production “easier” and cheaper. (It is also why so much moonshine is made from sugar instead of grain.)

Rye grain is also more expensive because it has a much longer growing season, so farmers must price their crops accordingly. Rye is planted in the fall and is not harvested for use until the early summer. Even as a very sustainable crop, it does not allow the farmer to utilize the land again until late in the growing season. Corn needs to be planted in the spring, but the rye plant will still be maturing and will not be ready to harvest until early June (in Pennsylvania), so farmers could not grow both plants on the same plot of land in a rotation. Same goes for wheat. Even spring wheat needs cool ground to be planted. (Spring wheat is planted in the spring instead winter wheat which is planted in the fall.) It wasn’t just the amount of grain and the growing season that made rye whiskey more expensive to make. The distilling process itself was more labor intensive and took longer to complete from start to finish.

Fermentation times were longer for rye-based mashbills than for corn dominant recipes. Some distillers kiln dried their raw grain which not only added a step to the process but required more fuel. The most used still design in the late 19th century in Pennsylvania was the chambered still which required oversight throughout the entire run. The stills were heated to a higher temperature than column stills, also requiring more fuel. The fuel, whether supplied by wood, coal, or natural gas, was manually added to furnaces that heated the boilers which produced steam. Steam was the lifeblood of the distilling plant. It was not only required to heat the mash cooker and still, but it was also used to power the machinery within the still house. Perhaps most importantly, steam heat was used to maintain a balmy temperature within the facility’s huge bonded warehouses all year round.

Most of Pennsylvania’s rye whiskey distilleries built multi-story brick or stone bonded warehouses. Most warehouses stacked 45-gallon barrels 3 high on each level. Each brick warehouse was fitted with miles of pipes fed with steam that maintained consistent temperatures anywhere from 75 to 90 degrees Fahrenheit. Today, distilleries like Buffalo Trace and Brown Forman use some steam heat, but those warehouses are “cycle heated,” which means they bring their internal temperatures to about 80 degrees for about a week before dropping it down again and repeating that process. Pennsylvania’s rye whiskey warehouses maintained a consistent temperature throughout the year. Venting windows enabled rising heat to escape and thick walls maintained the internal temperatures. The costs of heating 7-story, brick buildings were high, but Pennsylvania distillery owners clearly knew the benefits of using steam. While steam heating was not a part of what made Monongahela whiskey famous (steam heat was not an option until after the Civil War), it was certainly the decisive tradition adopted by rye distillers in the late 1800s and was traditionally maintained throughout the state until Prohibition.

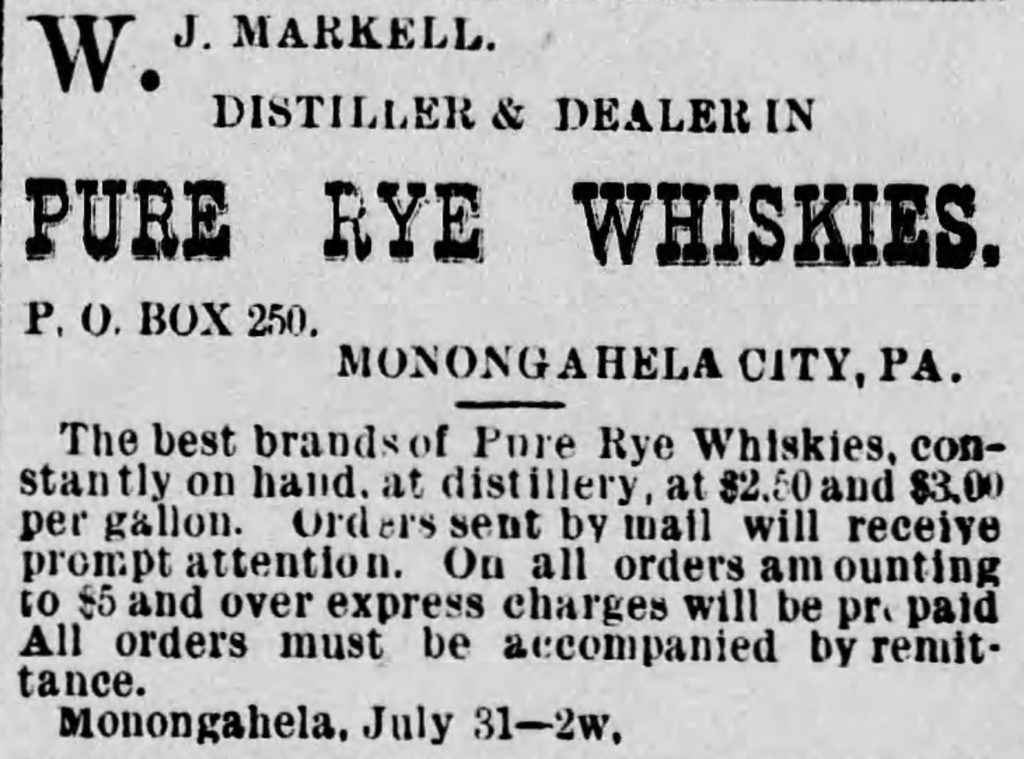

Pennsylvania and Maryland’s rye whiskey producers were very aware of how expensive their products were. They often bragged about it in their advertising. They understood that their products were superior and that the retail market held rye whiskey in high esteem. Distilleries in other states like Indiana, New York, Kentucky and Ohio also made rye whiskey, but they could not demand the high prices that Pennsylvania and Maryland could. Liquor men that wished to cash in on the prized Pennsylvania pure rye whiskey market even went as far as purchasing land in the Monongahela Valley on which to build their own distilleries. The public’s opinion was priceless, and Pennsylvania’s established distillers were not thrilled to have outsiders move in, but at least there was a shared interest in maintaining Monongahela rye whiskey’s hard-earned reputation. Even the new distillers spared no expense to compete with the established hierarchy. They hired experienced Pennsylvania or Maryland distillers and mimicked the traditional production methods to gain authenticity for their brands. The cost of making rye whiskey also helped to keep production capacity in check somewhat. While behemoth distilleries in the west were making bulk product for the liquor trade, Pennsylvania and Maryland were supplying a niche market with aged, pure rye whiskey.

2. Pennsylvania’s Distilleries Were Late Forming Corporations in Pennsylvania

While every other Pennsylvania industry had been forming corporations for generations, Pennsylvania’s distilleries were the excluded exception. State laws allowing for the incorporation of manufacturing industries specifically included language stating that distilleries must remain the only exception. This does not mean that companies in Pennsylvania did not hold charters in other states. Several companies in Philadelphia and Pittsburgh held charters in either New York, New Jersey, Delaware, or Maryland. The Hannis Distilling Company, as an example among many others, was founded and based in Philadelphia, while its manufacturing plants were located in Baltimore and West Virginia. The Hannis Distilling Corporation was organized under the laws of Maryland on April 28, 1871 and continued to operate its home offices out of Philadelphia.

Finally, in 1901, The McClain Corporation Act was passed allowing distilleries to incorporate. Once the restriction was lifted, the applications for corporate charters in the state of Pennsylvania began being filed. The first distilling company in Pennsylvania to form a corporation was the Pen-Mar Distilling Company in Waynesboro, Franklin County in September 1901. (The second was the Moss Distilling Co. in Port Royal, PA, Westmoreland County) Some distillery buildings in Western Pennsylvania’s 23rd district were constructed as late as 1910 and had only 2 or 3 years of production before they were forced to close due to license refusals by county judges. Just because the corporations were able to move in didn’t mean they would be embraced by the county courts. Pennsylvania’s old and established distilleries were slow to create charters and those that did incorporate maintained their ownership as majority stockholders in their own company. The only companies to own several distilleries under the same charter in Pennsylvania did not materialize until years after the passage of the McClain Bill. The independence maintained by Pennsylvania’s distilleries and the generally negative opinions they held about allowing out-of-state ownership fostered a unique environment within the state, especially in the west. This independence enabled them to determine their own futures even when confronted by the all-powerful Whiskey Trust.

The market for Pennsylvania pure rye whiskey was so strong that even with the countless events foretelling a national Prohibition, few Pennsylvania distillers believed that it was actually possible…even up to the last minute.

3. Rye Whiskey Distillers Didn’t Believe Prohibition Would Happen

A desire for temperance in alcohol consumption began almost as soon as the first distillers arrived on these shores. The push for national Prohibition, however, did not begin in earnest until about 50 years before the passage of the 18th amendment. We tend to forget that the seeds of the movement began as early as they did and took so long to gain national acceptance from Americans. While the concept of temperance was a shared dream for the majority of Americans, complete abstinence from alcohol was never more than a small minority opinion. America’s citizenry was a dynamic group with culturally differing drinking habits, religious beliefs, and political opinions. The country’s communities, clergy, and political representatives were always in flux which made it difficult to know which way the winds were blowing at any given time. The “wets” and the “drys” were slowly dividing the country, but many Pennsylvanians believed that our collective good sense would overcome the zealotry.

Nothing, it seems, solidifies a political party platform like a good moral issue. In 1869, the National Prohibition Party was organized in Chicago. 5 years later, the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union was founded. Rye whiskey distillers had been dealing with pushback on their industry for as long as they could remember. One of the more successful pieces of legislation to curb the growth of the liquor trade in Pennsylvania was the “Brooks Law” in 1887. It not only created distinct and separate licensing rules for wholesalers and retailers but gave local judges complete discretion over who would receive the licenses in the first place. This was a win for temperance supporters because they felt they could place sympathetic judges in local courts that would help them deny licenses and rid their communities of liquor. In many cases, they were successful in placing judges that helped to push out salesmen and producers, but certain counties remained strongholds that could not be swayed. The big tax dollars that flowed in from the distilleries in certain municipalities were far too beneficial, and the distillers knew they would never be denied licenses by their local courts. The heavy influence of the temperance crowd could be felt, however, in those same judges’ refusals to allow for new applicants. This way, they could appease the angry temperance crowd while allowing established businesses to carry on as usual.

While temperance opposition was an irritation for them, it never appeared to Pennsylvania’s distillers that the state would ever side against them. Pennsylvania’s whiskey men faced down a statewide vote for Prohibition in 1889 and won handily. The campaign for a dry Pennsylvania trudged on, and though several counties within the state went dry putting many whiskey producers out of business, the large producers continued to exist with a tolerable level of comfort. These remaining companies appeared untouchable. While other states were going dry, these whiskey men felt certain that Pennsylvania would not. In fact, they were correct in that Pennsylvania was not one of the 38 states to ratify National Prohibition. Unfortunately for them, that didn’t matter.

One can see the unwillingness to believe that Prohibition was imminent in Pennsylvania by the number of new companies formed and distilleries still being built well into the early 20th century. A distillery, at the time, required tens of thousands of dollars in investments (the equivalent of many millions today) to bring a plant up to production status and companies would not have invested so much into a new construction project if they didn’t foresee a bright future for their businesses. Western Pennsylvania saw dozens of newly formed companies, many of which were capitalized by wealthy men from other industries looking to diversify their incomes. The passage of the 1901 McClain Corporation Bill (allowing for corporatization of PA distilleries) began to slowly change the business landscape. Corporations, by their nature, engage the participation of board members and varied, outside interests. They cannot help but alter the locally focused, insular mindset of a business. Confident distilleries in Pennsylvania, even as WWI was ramping up in Europe, were remodeling their plants and continuing to fill their bonded warehouses with barrels. They were carrying on as if the rest of the country wasn’t falling in line with the temperance movement.

4. The Creation of Consolidation Warehouses.

In the early years of Prohibition, the government was forced to face the gaping holes in the Volstead Act’s logic. Ridding the country of the saloon and its distilleries meant ridding the country of one of its oldest, largest, and most complex industries. As a vertically integrated industry, the impact that the abrupt end to distilling was massive as it upended an entire supply chain. Distilling would not go away quietly. One of the major problems that arose almost immediately after the passage of the 18th amendment was what to do with all the whiskey that remained in the hundreds of bonded warehouses spread across the country.

On February 17, 1922, Congress approved the Concentration Act. It went into effect on April 7. Its purpose was to consolidate the contents of approximately 300 bonded warehouses across the United States into only two dozen and to save the US government the high costs associated with their management. You can read all about that HERE. Suffice it to say, the consolidation of all the whiskey in the country went to the powerful few. Those interests (namely, the Whiskey Trust) did not have the interests of rye whiskey at heart. They had failed to bring Pennsylvania and Maryland’s rye whiskey distilleries to heel at the turn of the 20th century and were likely more than happy to see those businesses fail. The Whiskey Trust was only concerned with the promotion and profitability of their own businesses and brands. The most powerful corporate interests backed their bourbon stocks and manipulated the government’s decisions on who would receive the permit assignments for concentration warehouses. Without a corporate umbrella over Pennsylvania and Maryland’s rye interests, there were fewer advocates to lobby for those states being home to America’s concentration warehouses.*

*Some of you may be wondering, “Well, wait a minute! What about Schenley?”

While Schenley Products Company was formed by Louis Rosenstiel in 1920, he was not able to secure a concentration warehouse permit for his distilling company’s warehouses in Schenley, Pennsylvania in 1922. Sol Rosenbloom’s Joseph S. Finch Distillery in Pittsburgh, however, WAS granted a permit. In 1924, Rosenstiel was able to purchase the Joseph S. Finch Distillery from Rosenbloom…along with its consolidation warehouse permit. Once he owned Finch, he transferred the contents of the company’s bonded warehouses to his own in Schenley, Pa. This single purchase was the springboard that launched Schenley Products Company into becoming one of the major players in America’s medicinal whiskey trade. A few years later, he secured 240,000 cases of Old Overholt Pure Rye Whiskey and 120,000 cases of Large Pure Rye Whiskey, two of the largest purchases of whiskey during the Prohibition era. In 1929, Rosenstiel purchased the George T. Stagg distillery in Frankfort, KY. Conveniently, the Stagg plant was one of the six distilleries in Kentucky to be granted a permit to help restore the country’s dwindling medicinal whiskey stocks. With twice the output capacity of Joseph S.Finch (Schenley), the purchase of Stagg was significant. While Schenley did act as an advocate for rye whiskey, he was not in a position to act in its interests in 1922. Nor did he have any real connection to the pre-Prohibition legacy of Pennsylvania or Maryland. Until 1920, Rosenstiel had been a spirits’ distributor in Cincinnati.

5. Post Prohibition Laws

As Prohibition was nearing its end and the inevitably of Repeal approached, Pennsylvania was in a particularly sticky situation. One third of the country’s whiskey stocks were being stored within its borders. Pennsylvania’s distillers and the liquor men preparing for a return to the billion-dollar business of making liquor were eager to get started. There was no doubt that demand would be high and those companies that could establish themselves early could stand to make a lot of money. Pennsylvania’s governor, Gifford Pinchot, however, was not interested in creating a competitive marketplace for distillers. Like so many others before him, he truly believed he could control the situation and enforce his morality through legislation. The day before Repeal, Pinchot was quoted saying, “Prohibition at its worst has been infinitely better than booze at its best.”

Governor Pinchot, who had been elected governor in 1931, was arguably the most influential person behind Pennsylvania’s exit strategy from Prohibition. As a resolute teetotaler, he held very strong feelings about the immorality of liquor and believed that the positives gained from Prohibition outweighed all its negative consequences. Pennsylvania’s new liquor laws would be drawn up to enforce Pinchot’s moral fanaticism. He was convinced that he had the answers on how to keep Pennsylvania under control. Though not all his plans would be realized, much of what he proposed shaped Pennsylvania into the control state that it has been for the last hundred years. Pennsylvania’s legacy of excellence in rye whiskey production would soon be lost to history.

Pinchot’s 5 cardinal points for his plan for Pennsylvania were:

- The Saloon Must Not Be Allowed to Come Back.

- Liquor Must Be Kept Entirely Out of Politics.

- Judges Must Not Be Forced into Liquor Politics.

- Liquor Must Not Be Sold Without Restraint.

- Bootlegging Must Be Made Unprofitable.

The governor was most vehemently opposed to people socializing at bars, saying he would “prohibit forever the open saloon.” He believed that bars invited corruption and fostered immoral behavior. Pinchot’s plan was to make it illegal to display drinks, mix drinks, or sell drinks at a bar. One of the most frustrating concessions he was forced to make in order to pass legislation was to allow private clubs to sell drinks. While ridding Pennsylvania of its bars was the most important piece of Pinchot’s plan to restore order to the state, this ban would only last as long as his final 2 years in office and would be lifted by his successor.

Pinchot’s plan to govern morality and keep politics out of liquor was not only going to be impossible, it was also highly hypocritical. Somehow, in Pinchot’s idealistic vision, placing the government in charge of liquor would keep politics out of liquor. He felt that his Liquor Control Board would act as a civil service organization, remaining neutral and keeping any one group from profiteering off liquor sales in Pennsylvania. The board would remove the courts from having to make licensing approvals as well. Before Prohibition, Pennsylvania’s local courts were given full discretion over who was given wholesale and retail licenses by legislation commonly called “Brook’s Law” which was enacted in 1887. Brook’s Law was devised by temperance idealists who believed that the courts would be sympathetic to their desire to curb licensing, and, in many cases, they were correct. When Prohibition was assured, the temperance advocates wished to do away with the Brook’s Law because some courts, who still had full discretion over licenses, were continuing to provide them. Pinchot wanted to remove the courts from their licensing role because he felt they politicized the process too much. Instead, 3 members of his liquor board would oversee licensing decisions and specific limitations would be placed on who could be approved. A restaurant, for instance, would need at least five hundred square feet of space, tables and chairs to seat at least 50 people, employ at least 3 people in the kitchen, and have what the board would consider “a good reputation.” Retail licenses for privately owned liquor stores would be removed entirely and a state store system put in place. Wholesale licenses would no longer be available to distilling companies which effectively ended their ability to make direct sales to customers. Without the ability to sell direct to customers, only those distilleries with connections to large distributing networks would remain viable.

Pinchot’s last 2 points seemed the most contradictory. Liquor, Pinchot believed, should not be advertised to the public and capitalistic competition should be eliminated. This, he felt would be so appealing to Pennsylvanians that it would drive down bootlegging. Of course, eliminating advertising would hinder the state store system’s ability to raise revenue. Opponents argued that a state store system would encourage illicit distilleries and illicit imports from out of state. Distillers argued that the costs of Pinchot’s plan would force prices up and would give neighboring states an unfair advantage. Bootleggers, they insisted, would be encouraged to sell at prices below the state. Pinchot, however, believed he would be able to keep costs and prices very low to outcompete bootleggers.

Pinchot’s flawed plan, though designed with all his best intentions, helped to reveal how ignorant he and others in government had become about how much the liquor trade had been reshaped by Prohibition. One of his most telling errors in judgement was his enthusiasm for the implementation of a floor tax. Pinchot initially believed that he could instantly inject $25 million into Pennsylvania’s coffers by demanding distillers pay a $2 tax on every gallon of liquor they owned that had been made before Dec 5, 1933. The largest owners of whiskey stocks in Pennsylvania, however, were National Distillers and Schenley, 2 of the 4 largest owners of US whiskey stocks in the United States after Repeal, otherwise known as the “Big Four.” (The “Big Four,” as they came to be known, were National Distillers, Schenley, Seagrams, and Hiram Walker.) While most Pennsylvania distillers were willing to pay the floor tax quickly so they could move on with preparations to get up and running, National Distillers, Schenley, and Continental/Publicker flat out refused to pay up. Pinchot believed they were bluffing and would eventually be forced to pay, but he vastly underestimated the size and resolve of the companies he was dealing with.

The largest of the liquor concerns protesting Pinchot’s floor tax was National Distillers which owned half of the United States’ whiskey stocks. The company’s president, Seton Porter, had 2 million gallons of whiskey tied up in Pennsylvania’s warehouses. While Louis Rosenstiel’s Schenley Distillers, Inc. was technically half the size of National Distillers with only 25% of America’s whiskey stocks, he had twice as much whiskey warehoused in Pennsylvania. He could not allow 4/5 of his whiskey stocks, amounting to 4 million gallons, to be taxed at $2 a gallon. Simon (“Si”) Neuman’s Continental Distilling Company, while not one of the “Big Four,” was still a force to be reckoned with. Neuman moved 50,000 cases of gin from their warehouses in Philadelphia to Camden, New Jersey and threatened to move their production facilities to Peoria. In fact, so much liquor was moved with such haste that Philadelphia’s police chief called the city’s Prohibition headquarters to report the sudden activity only to find that the transfer was entirely legal.

National Distillers, which owned Large Distillery and Overholt & Co.’s plant at Broad Ford, and Schenley Distillers, which owned Joseph S. Finch Company, also threatened to move their whiskeys and operations out of state. Pinchot was quoted by the Harrisburg Telegraph as saying, “I have seen grandstand plays before and they leave me cold…The Legislature will see this crude and idle threat for what it is.” Meanwhile, the mass exodus of whiskey and liquor from the state significantly lowered the amount of goods that Pinchot was attempting to tax in the first place. National Distillers and Schenley made good on their threats and shut down production at all their Pennsylvania plants and furloughed over a thousand workers. The unemployment relief costs to the state for all those furloughed distillery workers combined with the court costs of fighting the distillery companies were unsustainable. On top of these failures, accusations were made that a Schenley Products Company lawyer had been approached with an offer to secure 5/6 of Pennsylvania’s state store system’s business…for a price. A House committee was called to perform an inquiry into the matter. Something had to give.

In late December 1933, a tentative compromise was made. The agreement, after being finalized, allowed the state store system to open on January 1st with stocked shelves. The state’s attorney general explained the compromise to the Philadelphia Inquirer; “They will pay into the general fund of the State Treasury this year a floor tax exceeding $13,000,000. They have agreed not to ask to have this tax refunded even if someone else succeeds in having the law declared unconstitutional. The State Liquor Control Board has agreed to buy approximately 6,500,000 gallons of whiskey from these concerns during 1934.” He went on to explain how the compromise would help pay for schools and other government projects. This arrangement, of course, was much more advantageous to the liquor companies. The onus was now on the state stores to sell the products they purchased and collect the floor taxes through sales, all somehow without the benefit of advertising. Much of the liquor the state purchased was unaged, but the liquor companies assured the state that after three years, it could be sold to great benefit. After all, the total amount purchased was only a half year’s supply of whiskey for Pennsylvania when compared to those years before Prohibition. Selling all that liquor seemed an easily achievable task…on paper. By October 1934, however, less than 1/6 of the $12 million expected to be collected from the 6.5 million gallons of taxable liquor was realized. The state of Pennsylvania’s new Liquor Control Board was receiving its first painful lesson in learning to sell liquor. (It is still learning today…)

The common thread connecting Pinchot’s plan and the manipulations by the big distilling companies, both of which enabled the state store system, was a shared interest in reducing the likelihood that Pennsylvania would return to being a competitive distilling state. Pinchot didn’t want a return to a place where liquor firms held too much power over government, so he made a deal to allow the companies with too much power to be the “devil he knows.” Seton Porter, Louis Rosenstiel, Si Neuman, and a handful of other company owners controlled almost all the liquor in the country and perhaps it was better, in Pinchot’s mind, to maintain a small number of distilleries in Pennsylvania and purchase everything necessary for the state stores from a handful of sources. The “Big Four” were happy to help keep Pennsylvania’s distilling industry in check and maintain the status quo.

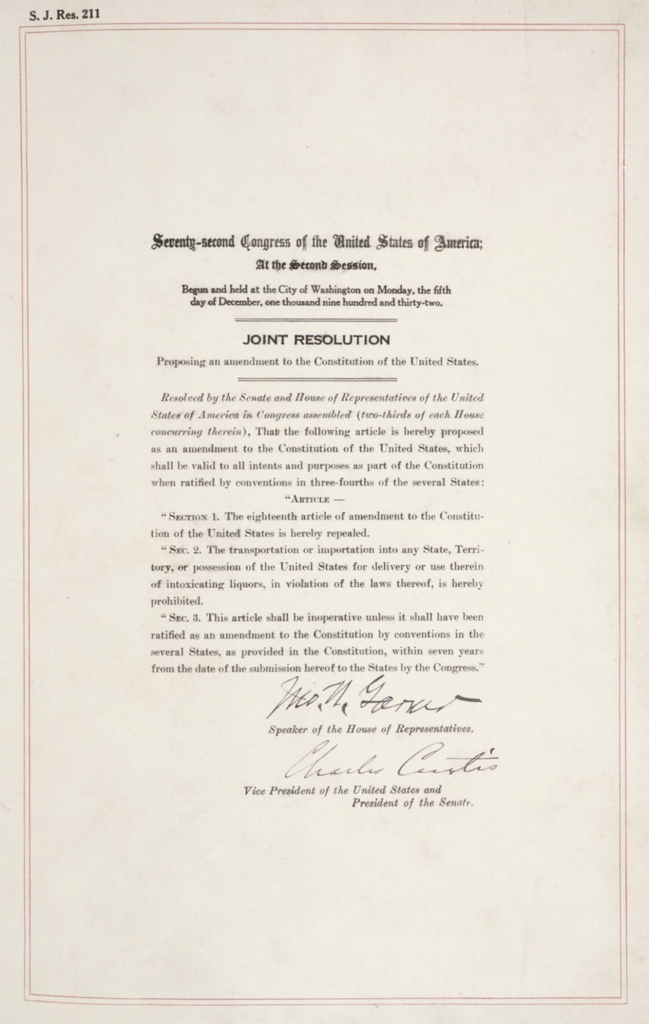

The United States Government Limited New Development

In November of 1932, Franklin Delano Roosevelt was elected President of the United States after running on a campaign to end Prohibition. The joint resolution to enact the 21st Amendment as part of the US Constitution, otherwise known as the Blaine Act, was passed by Congress just days after the election on December 5, 1932. After Roosevelt was sworn into office in March, the ratification process began in earnest. With a flair for the dramatic, Ohio and Pennsylvania ratified on December 5th, 1933 with the hopes of an instantaneous repeal one year after Congress’ resolution. Utah was clincher as the 36th state to ratify the amendment at 3:32 and ½ minutes MST (Mountain Standard Time) or 5:32 in Pennsylvania’s Eastern Standard Time. All said and done, Prohibition lasted 13 years, 10 months, nineteen days, seventeen hours, and 32 ½ minutes.

- Michigan: April 10, 1933

- Wisconsin: April 25, 1933

- Rhode Island: May 8, 1933

- Wyoming: May 25, 1933

- New Jersey: June 1, 1933

- Delaware: June 24, 1933

- Indiana: June 26, 1933

- Massachusetts: June 26, 1933

- New York: June 27, 1933

- Illinois: July 10, 1933

- Iowa: July 10, 1933

- Connecticut: July 11, 1933

- New Hampshire: July 11, 1933

- California: July 24, 1933

- West Virginia: July 25, 1933

- Arkansas: August 1, 1933

- Oregon: August 7, 1933

- Alabama: August 8, 1933

- Tennessee: August 11, 1933

- Missouri: August 29, 1933

- Arizona: September 5, 1933

- Nevada: September 5, 1933

- Vermont: September 23, 1933

- Colorado: September 26, 1933

- Washington: October 3, 1933

- Minnesota: October 10, 1933

- Idaho: October 17, 1933

- Maryland: October 18, 1933

- Virginia: October 25, 1933

- New Mexico: November 2, 1933

- Florida: November 14, 1933

- Texas: November 24, 1933

- Kentucky: November 27, 1933

- Ohio: December 5, 1933

- Pennsylvania: December 5, 1933

- Utah: December 5, 1933

The resolution to add the 21st Amendment to the Constitution of the United States was never going to be an easy transition for the country. Many people believed that Prohibition could still be saved, but FDR was determined to follow through on his campaign promises to end it. Roosevelt was keenly aware of the complexities that awaited him in rebuilding the liquor industry. It was one thing to halt liquor production and the intricate excise system that the US government managed, but it was a vastly different thing to rebuild from scratch what took nearly 100 years to develop. Roosevelt sought advice from his team of advisors, also derisively known as his “Brain Trust”. The changes that he put into place in 1933 after these consultations were not exactly what the country’s liquor interests had in mind when they sought reform.

The guiding principle behind the Blaine Act in 1932 was that liquor would be returned to the states. Each state had been drawing up their own plans for how to proceed once Repeal was enacted. But in late November 1933, the Roosevelt administration’s drafts for “Codes of Fair Competition for the Distilled Spirits Industry” were drawn up by the Secretary of Agriculture and the President’s Special Committee for the “Control of Alcohol and Alcoholic Beverages.” The plan would impose rigid Federal control on the whole liquor business until Congress was able to tackle the subject. The code’s main provisions were:

- A Federal Alcohol Control Administration would rule the industry without benefit of any liquor representatives.

- No additions to present plant capacities except by a certificate of necessity from the FACA and absolute control of production and distribution through a quota system.

- Power to fix prices.

- An agreement with the Secretary of Agriculture to pay “parity” prices established by him for raw materials.

America’s distillers swarmed on Washington. They all hoped for some Federal control over the political fiasco happening within their own individual states, but this was far more than they bargained for. The decision to freeze capacities of distilleries as they existed before December 5th was a huge blow to the distilling interests. Most of them were undergoing rebuilds and would never be able to complete construction under such a short and unexpected deadline. This would force anyone undergoing construction to scrap their investments. The “drys,” already incensed over Repeal, were finally getting a win. Perhaps the only industry insider smiling was National Distillers’ president, Seton Porter, who knew that these codes would allow him to maintain his position of dominance above his competition. Several of Pennsylvania’s distilling interests were stopped in their tracks.

6. The Loss of Generational Knowledge

Any distiller will tell you that learning to distill is a lifelong process. Before Prohibition, master distillers instructed each new generation of rye whiskey distillers. A distiller was often a trained mechanic and engineer. He was fully capable of operating and repairing any facet of the equipment on site. He was a skilled agriculturalist whose understanding of grain came from his own personal experience with farming. The multitudes of minutia that each distiller was expected to know from yeast propagation to copper welding were passed from generation to generation. With the advent of Prohibition and 13 long years without legal distilling, a generation of rye whiskey makers were lost.

To add a bit of perspective on just how seriously rye whiskey makers took their craft: In 1870, James Frost was hired as distiller by John Gibson for his John Gibson & Sons Distillery near Belle Vernon, Pa. After two years with the Gibson Distillery, he was transferred to work at Gray’s Landing Distillery. He remained with Captain William Gray’s distillery for eight years where he thoroughly learned the business. Captain Gray is the only man I have ever seen listed in the US census as a “Master Distiller” with “Journeymen” and other “Distillers” listed as neighbors and tenants over time. This means that Frost, already a distiller was not up to snuff and had to be sent for 8 years of apprenticeship under a master before he was invited back. By 1880, he was finally offered the position as distiller at Gibson Distillery, which he accepted. Frost remained with the company for 22 consecutive years (1902). Frost then took over the proprietorship of the Hotel Birmingham in Belle Vernon. His sons were also involved with distilleries. His son, Harry W. Frost, worked at the Moss Distillery in Port Royal, while James R. Frost, became a distiller for the Dillinger Distillery. THIS is what I’m talking about when I say that they took it seriously and there was A LOT TO LEARN.

The distillers that were put out of business by Prohibition launched their family businesses around the time of the Civil War. Their sons and grandsons were running complex distribution networks that shipped their whiskeys around the world. Most third and fourth generation distillers had investments in other businesses such as banking, coal, iron, steel, oil and gas, or railroads. They were able to shift their companies in other directions when Prohibition came to pass. They were also, by the 1920s, in their 60s, 70s and 80s. Over the 13-year period that Prohibition remained the law of the land, most of the men that owned rye whiskey distilleries or worked as master distillers in their plants were dead. Their sons took on new business roles and found success elsewhere. When the 21st Amendment repealed Prohibition, there were very few men alive that could teach the proper techniques and instruct a new generation of whiskey makers. Those that did live to see the 1930s were in their 80s and their new employers had a different idea of what production should look like.

7. Distilleries and equipment had all been dismantled and sold off.

Once Prohibition was enacted and the die was cast, the distillery owners sold off all their equipment. Much of the equipment was sold for scrap so the new company moving in could redesign the space for their own needs. Many of the steam-heated warehouses were converted for storage purposes and the steam pipes were stripped. Copper was valuable as scrap metal and many facilities were robbed of any copper pipe that remained.

Perhaps the biggest loss to Pennsylvania is the loss of its chambered stills. While it was well known that chambered stills with their copper doublers and long, winding worm pipes were the ideal still design for making pure rye whiskey long after Repeal, it seems distilling companies lost interest in the more expensive and labor intensive process after the 2nd world war. They all but disappeared from the industry. Even though they were the standard still used across the board to make rye whiskey, they were replaced by the column still because that was the preferred still for large-scale, industrial whiskey production.

8. The success of rye whiskey, unfortunately, led to its failure.

Now we come to it. When understanding the disappearance of Pennsylvania rye whiskey, one must address the elephant in the room…the Whiskey Trust. The influence that the Whiskey Trust has had on the American distilling industry is immeasurable. Its very formation was with the intent to control and manipulate whiskey production and, therefore, stock market values and retail prices. The trust’s board members learned from their missteps over time and seemed, even in their losses, to always win. It would cleverly adapt over time to retain its dominance and control over the industry and seemed to have connections everywhere to aid its ascent. The only stubborn mule that they couldn’t bring to heel were the Pennsylvania and Maryland Pure Rye Whiskey markets. The distilleries in Pennsylvania suffered from the same overproduction issues and grain shortages that everyone else did, but they were able to maintain their integrity because they existed within their own niche category. Their ability to work together to stem overproduction when it was called for and the larger, family-owned companies maintaining their independence allowed them to weather adversity. Pennsylvania rye whiskey producers could do what no one else could- say no to the Whiskey Trust. Ironically, this same successful independence may be the most significant reason that Pennsylvania was not able to weather the storm of Prohibition.

When I talk about the Whiskey Trust here, I’m not talking about the Whiskey Trust as it existed in the 1880 and early 1890s. (To learn more about the Whiskey Trust, READ THIS.) What I’m referring to is the Whiskey Trust in its new corporate suit after 1895- The newly formed American Spirits Manufacturing Company and its subsidiaries. After the Sherman Anti-Trust Law was passed, the money and the influence of the Whiskey Trust needed to be channeled into a new, legal strategy. Representatives from their subsidiary companies were sent out to begin purchasing all the distilling interests that could be obtained. The desire to control the industry was never tamped down by the Anti-Trust Laws. If anything, it gave the company an advantage by allowing it to act as a benign parent company. Their scheming was done by their subsidiaries, after all. The newly formed trust’s first efforts were to create legal combines of distilleries. They began in Kentucky.

Due to financial pressures and grain shortage issues in the late 1890s, Kentucky’s distillers were not averse to being given the option of forming a combine. By 1899, 52 of those combined distilling companies were bought up by the reorganized Whiskey Trust. They were organized under the laws of New Jersey into the “Kentucky Distilleries and Warehouse Company.” This is often described as an independent company, but it was operating throughout its existence as a wholly owned subsidiary of the American Spirits Manufacturing Company (Whiskey Trust).

During this same time, a competing interest for the American Spirits Manufacturing Company (also based in New York) snatched up three Kentucky distilleries to put under its own umbrella. The New York and Kentucky Company, whose president was the infamous William B. Duffy (of Duffy’s Pure Malt Whiskey), purchased and owned all of the stock of the following companies: The George T.Stagg Co., Frankfort, Ky.; The E.H.Taylor, Jr. Co., Frankfort, Ky.; The Kentucky River Distillery, Frankfort, Ky.; The Erie Distilling Co., Buffalo, N.Y.; The Duffy Malt Whiskey Co., Rochester, N.Y.; The Rochester Distilling Co., Rochester, N.Y.; The Wolcott Co., Rochester, N.Y.; The Columbia Distilling Co., Albany and Waterloo, N.Y. The insolvency of Kentucky’s distilleries at the end of the century, ironically enough, became their saving grace.

We now know that it was the placement of many distilleries under the umbrella of a single corporation that transformed the American distilling industry into what we recognize today. The large corporations, owning many facilities and most of the whiskey stocks, allowed them to navigate government pushback and stand their ground after Repeal. The Whiskey Trust may have been crooked, but it was its strength in numbers that would ultimately win the day. This win that Pennsylvania’s distillers had over the Whiskey Trust in the late 1890s and up to Prohibition may have been admirable and may have allowed them to maintain their integrity, but the future would bear out why the independence of these distilleries did not work out well in the long run.

Without the ability to bind together under a parent corporation, there was no captain steering the ship. There were no powerful advocates to allow rye whiskey to win the day when the concentration warehouse permits were issued. There were no great men to insist that you have to spend money to make money. Greed and the desire to make whiskey as quickly and cheaply as possible would always be the will of the Whiskey Trust. Whether it was in Peoria before Prohibition or in any of the distilleries that were being operated by the trust after Prohibition, the column still and the industrial scale model would always be the priority. There unfortunately was no place for rye whiskey production in this corporate model.