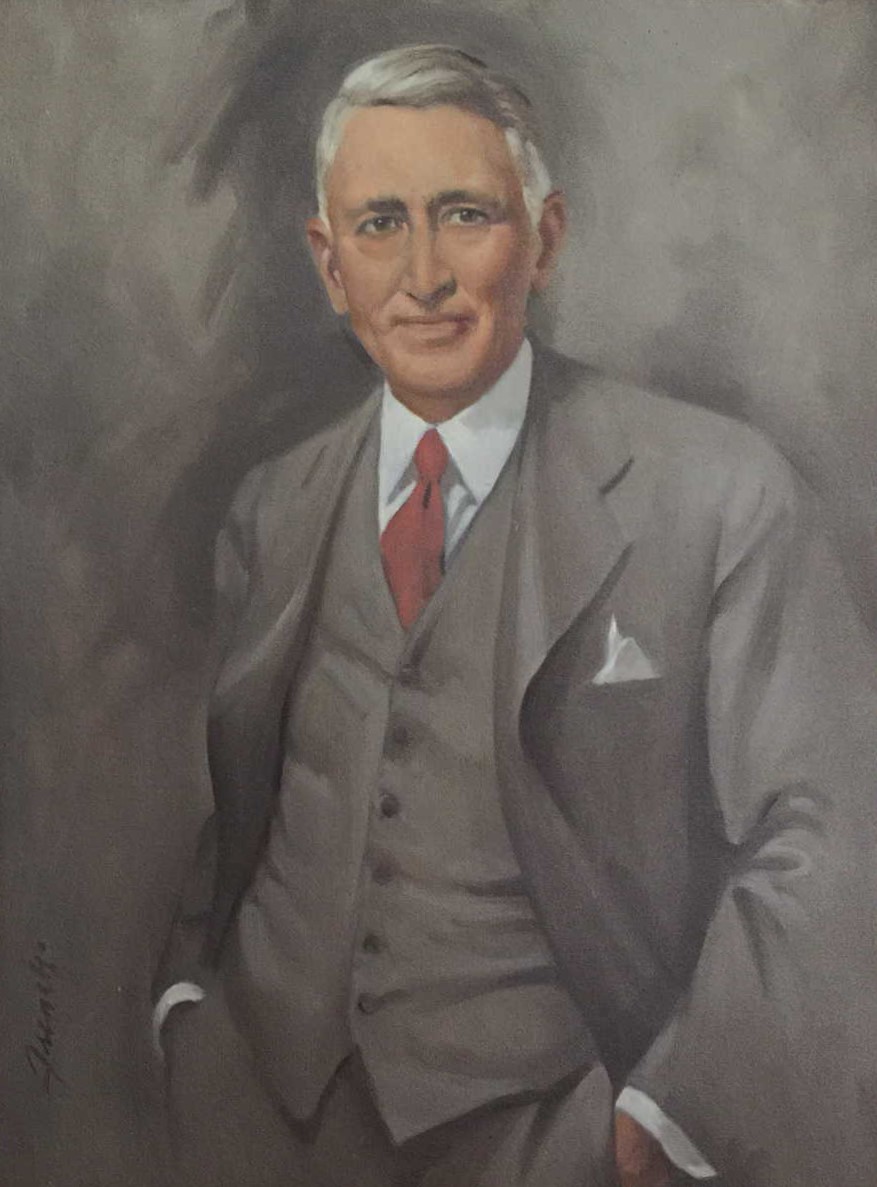

William E. Kricker was the master distiller for Baltimore Pure Rye Distilling Company after Prohibition. He was the man behind B.P.R. rye whiskey and Old Ruxton rye…but why was he so adamant about making those traditional rye mashbills, and what made him so significant to Maryland rye? I believe the answer lies in his own history.

Born in 1870 in Portsmouth, Ohio, William (Willie as a youth) was son to Mathias and Margaret (Myers) Kricker. His parents were German immigrants that welcomed their youngest son later in life. Mathias was 59 and Margaret was 44 when William was born. William was only 20 when his father passed away. He and his mother would settle into the home of William’s older sister, Louise Balmert, after Mathias’ death. Louise’s husband, Simon P. Balmert, was a popular wholesale liquor dealer in Portsmouth, so it is quite likely that William’s early education in distilling began through his relationship with his uncle. (William’s older brothers were closer with Simon, but they were also closer in age- William being 21 years younger than his brother-in-law.)

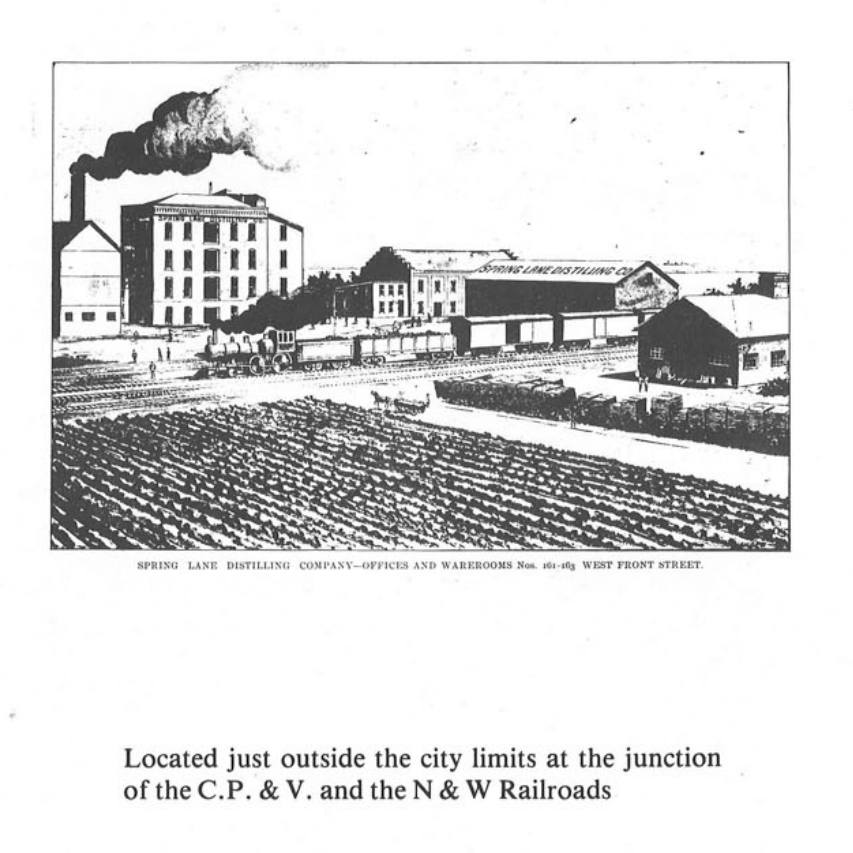

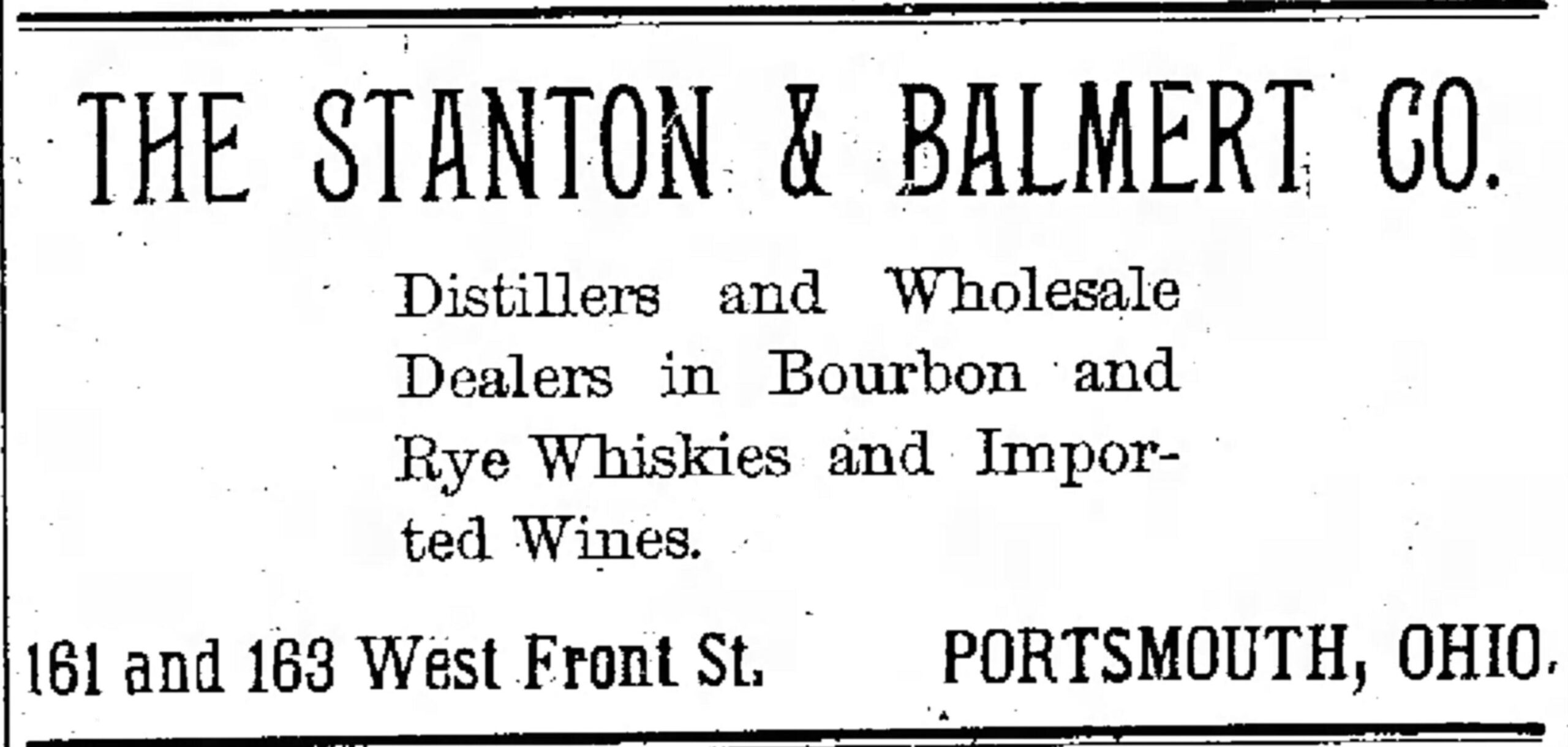

When William was just 7 years old, the Stanton Bros., an Ohio distilling company, dissolved their business, but a partnership was formed between Michael Stanton and Simon P. Balmert. Together, they formed Stanton & Balmert and operated their liquor business in Portsmouth for another decade before the men invested in another distillery in 1887. The Spring Lane Distillery Company, located about a mile and a quarter north of the city, was incorporated on March 30, 1887 with a capital stock of $50,000.

Stanton and Balmert maintained their offices at 161-163 West Front Street in Portsmouth. George E. Kricker, William’s very successful older brother, was brought on as manager of the plant. William was later hired as a distiller when he came of age. Within just 5 years, Stanton & Balmert tripled their distilling company’s value and doubled the plant’s capacity to 100 barrels per day.

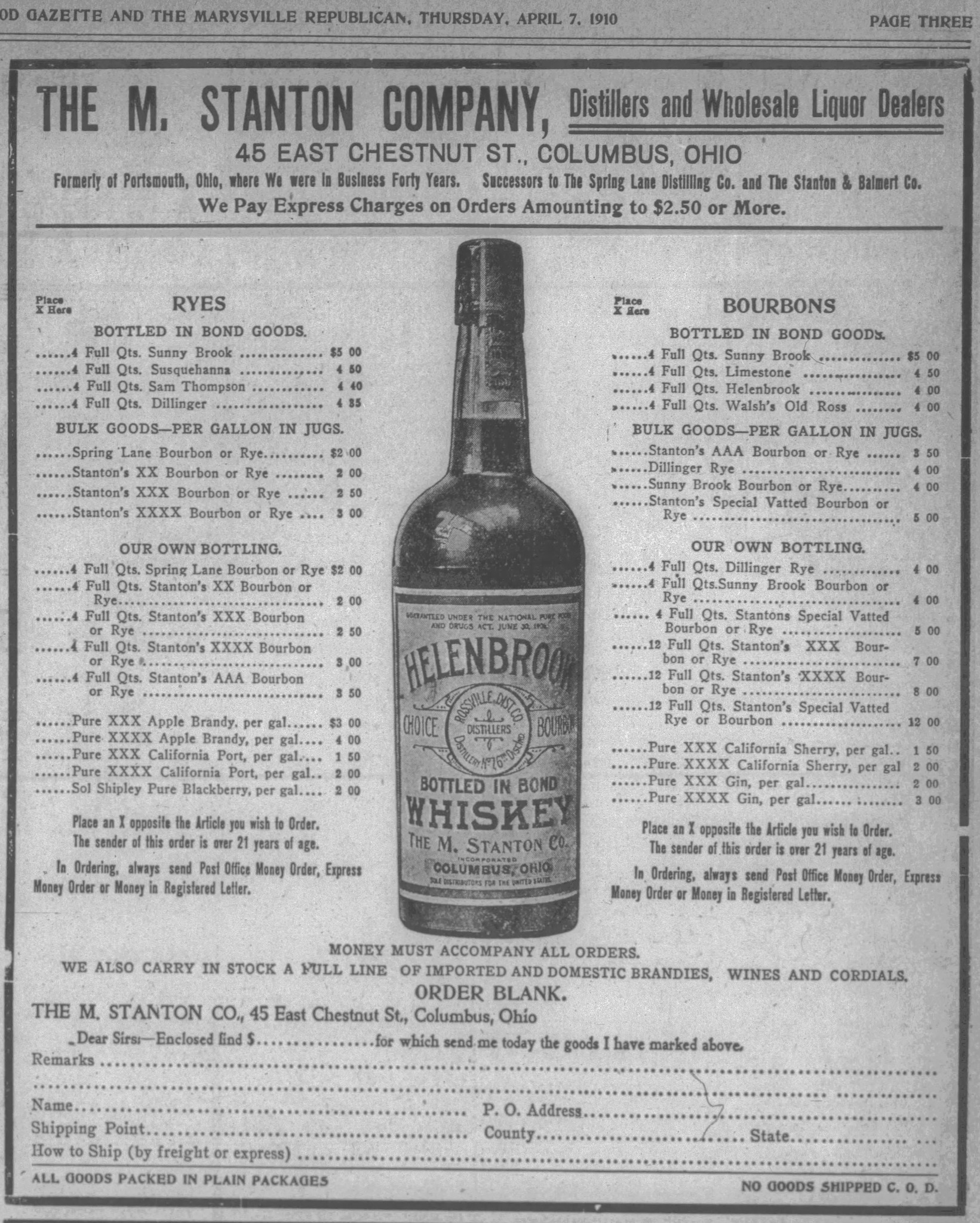

Simon P. Balmert died suddenly in 1894, but the company carried on as Stanton & Balmert until the early 1900s. Michael Stanton moved the company to Columbus, Ohio and changed its name to the M. Stanton Company, but he would maintain the claim to the company’s 30-year history in his ads.

William Kricker married Catherine Adams in 1904 and relocated to Baltimore, the city of his new family. That same year, William E. Kricker, along with Michael C. Winand, J. Frank Shipley, Thomas J. Winand, and Martin L. Jackson incorporated the Maryland Culture Yeast Company with a capital stock of $1000. Not the largest startup, but it was an ambitious one. The plan was to manufacture yeast, but it’s unclear how successful they were. By 1910, William was listed in the census as a distiller again, and William and Catherine are recorded as living within the household of George Adams, William’s father-in-law. It is difficult to know where he was working as a distiller at this point, but all signs point to him working at the Pikesville Distillery, operated by L. Winand & Bro. in Scott’s Level (Roslyn), Maryland. His association with the Winand brothers through their yeast company certainly points in that direction. This assumption makes more sense when one considers how strongly William Stricker stressed his “Real Rye-E” rye whiskeys in the late 1930s. (More research is needed here.)

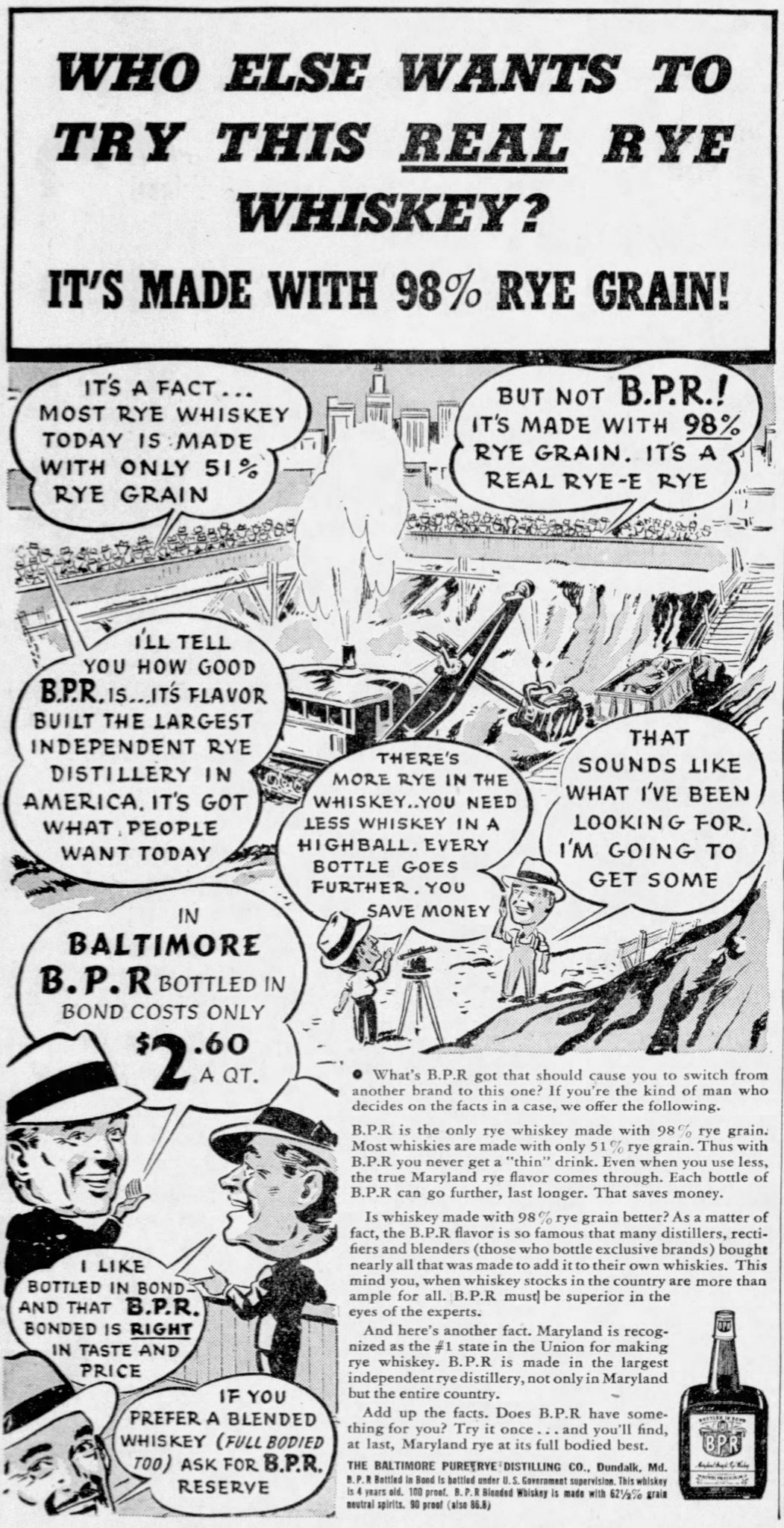

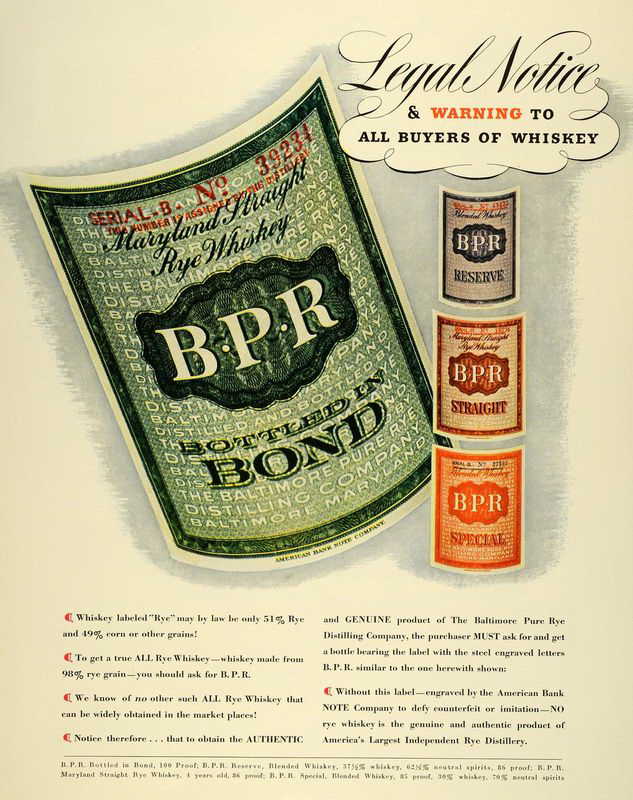

By the early 1930’s, most of the pre-Pro rye whiskey manufacturers/distillers were gone, but William was one of the young men with experience from the industry that would live to see the other side of Prohibition. He was only 63 years old the year of Repeal and would live for another 26 years. He may not have been able to manufacture the old Pikesville rye brand anymore (that brand now belonged to Andrew Merle of Standard Distillers), but he would maintain its traditional recipe and maintain a traditional yeast strain after Repeal. William E. Kricker’s education in distilling rye whiskey for the Winand Brothers certainly seems to have informed his distilling choices after Prohibition. It almost appears as if he was frustrated with the industry’s choice to reduce the quality of rye whiskey. His newspaper ads certainly reflect a distaste for cheaper, 51% rye whiskeys and stress the authenticity of his own products. His knowledge of yeast and the process of making pre-Pro rye are reflected in the whiskeys that he produced at Baltimore Pure Rye Distilling Co. His insistence on waiting until his ryes were 4-year-old bottled-in-bond whiskeys before putting them on the market in 1938 also speak to his commitment to preserving and respecting the traditions he was so familiar with. Anyone that’s tasted B.P.R. rye whiskey from the 1930s and 40s knows- They’ve tasted his success for themselves.

*P.S. I think it’s important to recognize and research these old distillers- if only to shine a spotlight on their contributions to the industry. They inspire me, and I hope they inspire you as well! The distillers seem to get lost among the stories about the owners of distilleries. Rich men did not make whiskey, they traded in it. It’s the same with artists in any field of expertise. The craft of distilling has always been in the capable hands of the talented, average person. To see so many distillers enter into the industry today with their own ambitions and their own skillsets is just as inspiring and just as worthy of recognition- especially when they’re making an excellent product. William E. Kricker sought to maintain the integrity of rye whiskey for as long as he lived, and he deserves to be more well known.