I’ve been wanting to write about Gwynnbrook for a long while. Unfortunately, Gwynnbrook isn’t a distillery name most whiskey enthusiasts are familiar with, but a distillery doesn’t have to be a household name to be a big deal for American whiskey history, folks! I think we should set some things straight- If you google “Gwynnbrook Distillery”, Google’s artificial intelligence will tell you that “Gwynnbrook was one of Maryland’s most notable distilleries, along with Pikesville. It was the source of whisky used to bottle Mount Vernon Rye, a brand named after George Washington’s distillery.” (Where’s that facepalm emoji when you need it?!) The first sentence gets a pass, but NO, Gwynnbrook was NOT the source of Mount Vernon Rye- though, to be fair, there were medicinal bottles of Mount Vernon Whiskey bottled by the American Medicinal Sprits Company that were sourced from pre-Pro rye whiskey stocks manufactured at Gwynnbrook Distillery. And NO, Mount Vernon was NOT named after George Washington’s distillery. (He didn’t sleep or eat there either😉) Mount Vernon rye, which was manufactured in Baltimore, was named after the neighborhood in Baltimore called- you guessed it!- Mount Vernon. Gwynnbrook WAS a Baltimore-based distillery, just like the Hannis Distillery, which was responsible for the Mount Vernon brand. But enough of what’s wrong with AI’s atrocious summaries of American whiskey history, let’s get back to the facts!

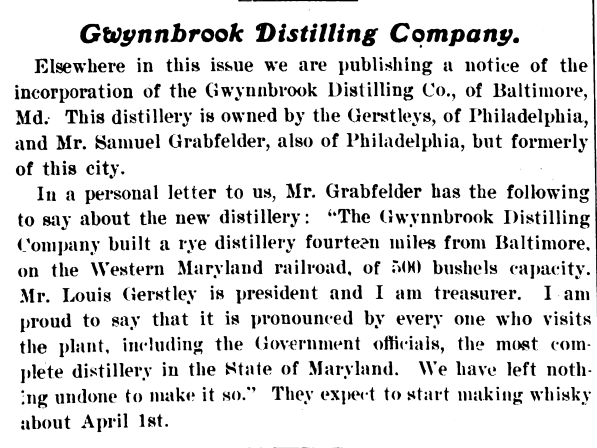

Gwynnbrook Distillery’s foundations were laid in the autumn of 1905 along the Western Maryland Railroad between Gwynnbrook and Ownings Mills. Mr. Frank J. Shipley, who had been secretary of the Winand Distilling Company and manager of its plant (makers of Pikesville Rye), would act as the new company’s first president. He would also assume management of the plant once it became operational the following year. The architect for the project was J.H.Krone, and the coppersmith hired to fit up the plant was Mr. Martin J. Kavanaugh. The brick and stone distillery and its fermenting rooms were designed to be 72 x 100 feet and 3 1/2 stories tall. Its brick boiler house was 36 x 46 feet. The bonded warehouse had a stone foundation with walls made of corrugated iron. This first warehouse was 60 x 72 ft at its foundation, and 9 stories high, but more warehouses would follow in time. The distillery functioned 9 months per year, producing an estimated 10,000 barrels per year. When Shipley was asked why he decided to build along the Western Maryland Railroad in Baltimore, he said:

“The reputation which Maryland rye whiskey has attained was the controlling factor. Then, too, at our site we have excellent water, which was an important consideration.”

(Spoken like a seasoned Maryland distiller who knew his mind.😊)

The early 1900s were a time of considerable investment in Maryland rye. The Baltimore-based distilleries in Canton were highly competitive with one another, and the Federal Distilling Company was enlarging its capacity in 1905 with an aim to be the biggest in the world! (Their aim was to manufacture 1,000 barrels a day.) During this time, the Philadelphia-based Louis Gerstley, of Rosskam, Gerstley & Co. (A large, well-connected Philadelphia liquor firm and makers of Old Saratoga Rye), took over the role of President of Gwynnbrook. The company’s future looked promising. Just as the whiskey in Gwynnbrook’s 9-story warehouse was reaching 4-years of age in 1910, huge summer rains and flooding began wreaking havoc on Baltimore’s businesses. The foundations of Gwynnbrook’s warehouse were compromised, and half of the building collapsed into a heap of debris and mangled iron beams. The only thing holding up the other half of the building was a fire wall between its two halves. $100,000 in losses were sustained, but construction crews were on site just 4 days later to assess the situation and clear away debris. The plant would soon be back in fighting shape.

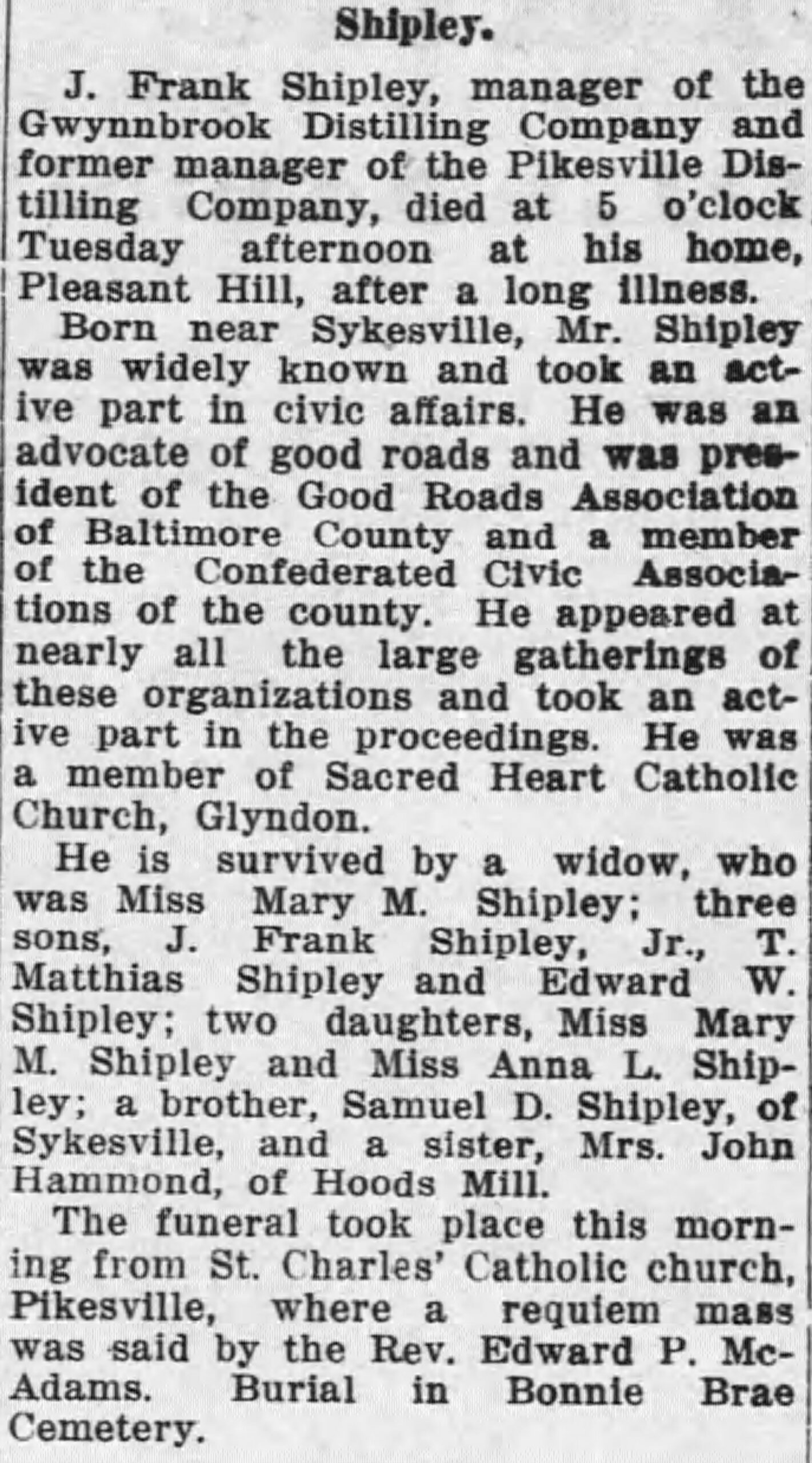

In September 1915, Gwynnbrook lost its founder and plant manager with the death of J. Frank Shipley. Shipley had been a big part of the Maryland rye whiskey industry- He founded the Maryland Culture Yeast Company in 1904 with Michael C. Winand, Thomas J. Winand, and Martin L. Jackson, and he had been manager at the Pikesville plant in Roslyn. The last years of rye making in Maryland before Prohibition were close at hand. By 1919, the property at Gwynnbrook was sold at auction to Morris Schapiro and his partner, John Roney, of the Boston Iron and Metal Company (a Baltimore-based scrap metal business) for about $15,500. I should add here that Morris Schapiro was one of the few men benefiting from and capitalizing on the loss of America’s distilling industry just before Prohibition. In large auctions selling off distillery properties across Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Kentucky, there were often just two men bidding. One was Morris Schapiro, and the other bidder was Daniel K. Weiskopf. Daniel K. Weiskopf had been in the business of buying distillery properties for the Whiskey Trust since the 1890s as head of the Distillers Securities Corporation, a subsidiary of the American Spirits Manufacturing Company. Its interesting to see these two men finding common interest during those years, especially when you see what happens next…

Morris Schapiro’s initial plan (or at least the plan he explained to the courts) was to scrap and sell off the plant as salvage. Scrap and salvage of very large properties, ships, and the inventory of iron/metal manufacturing companies was, after all, the business he was in. Articles published in the Baltimore Sun in December 1919 explained that the property at Gwynnbrook was going to be converted into a canning facility and that the 200 acres surrounding the plant would supply said canning facility with corn and tomatoes for that purpose. Of course, after Schapiro began the process of dismantling the property, he and John Roney decided that using the plant to manufacture medicinal whiskey would be more profitable. This may or may not have been due to the number of armed and violent thefts that were taking place in the weeks after their purchase of the distillery (December 1919- January 1920). In 1920, SOMEHOW Schapiro was able to secure a license to manufacture medicinal whiskey. Yes, you read that right! Between November 1920 and January 1922, Gwynnbrook Distillery was engaged in the production and sale of medicinal rye whiskey- DURING PROHIBITION! Court documents state that Schapiro and Roney hired the plant’s previous superintendent to oversee production, but it’s unclear who that could have been. (Perhaps J. Frank Shipley, Jr.?) Whoever had been making the whiskey, the plant ceased production in January 1922. Over their 2 years of active production, the plant manufactured 518,541.79 gallons of rye whiskey. It was stored on-site in Gwynnbrook’s warehouses which, unfortunately, opened the owners up to armed theft once again.

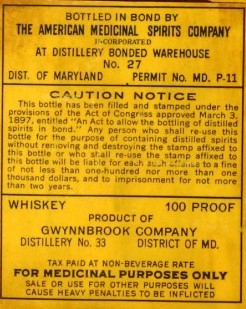

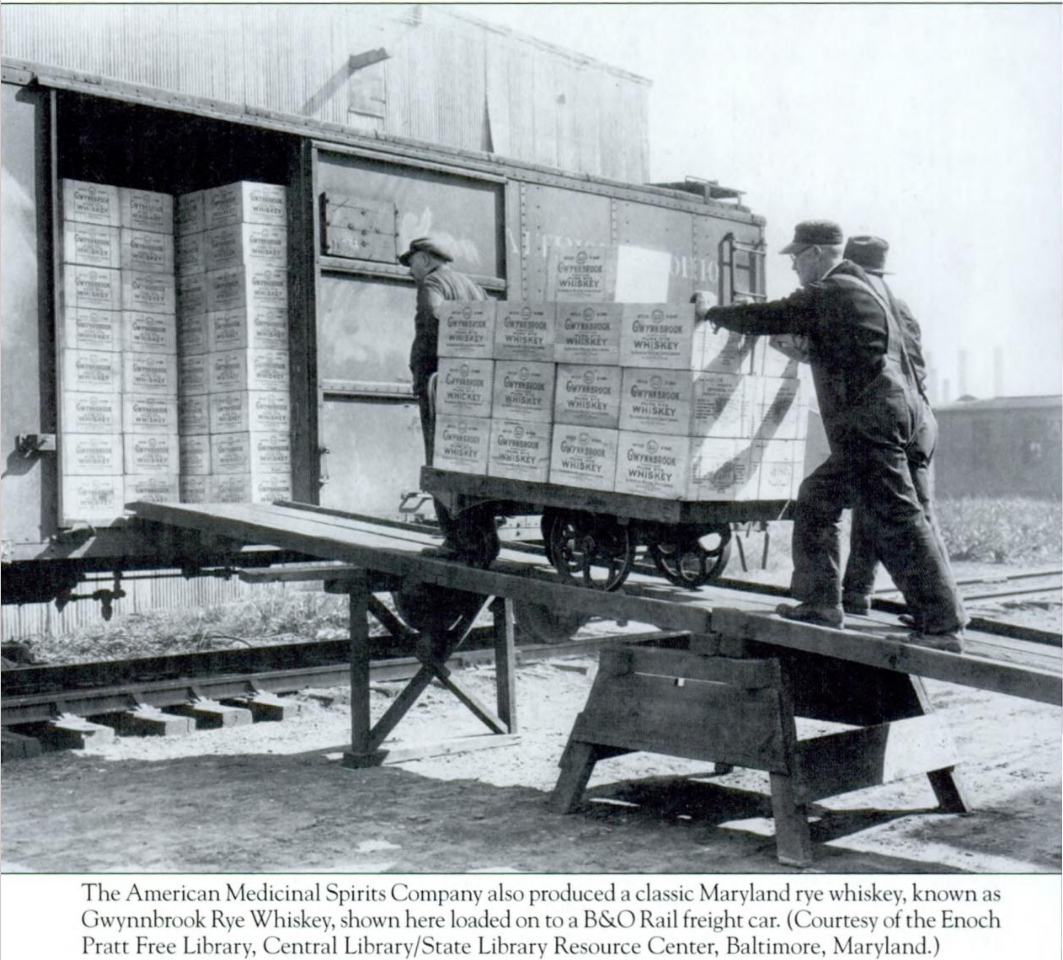

By 1924, the Dept. of Internal Revenue ordered that the contents of the bonded warehouses at Gwynnbrook be moved to the Baltimore Distilling Company’s concentration warehouses, which were owned and operated by the American Spirits Manufacturing Company, aka the Whiskey Trust. The sale of the whiskey belonging to the Gwynnbrook Distilling Company took place in intervals over the course of 7 years between 1927 and 1933. Morris Schapiro and John Roney’s barrels of rye were represented by 60 warehouse certificates (net profits in 1928 alone reached $630,027.29), all of which were transferred into the care of the American Medicinal Spirits Company. (The American Spirits Manufacturing Co.’s name was changed to the American Medicinal Spirits Co. in 1927, btw.) Most of those Gwynnbrook rye whiskey barrels were bottled by the AMSC as Mount Vernon Pure Rye Whiskey, though some did go into bottles labeled Gwynnbrook Pure Rye, as well. Any rye whiskey sold as Gwynnbrook Rye Whiskey by the Gwynnbrook Distilling Company before 1925 was sold by Morris Schapiro under his own license to do so.

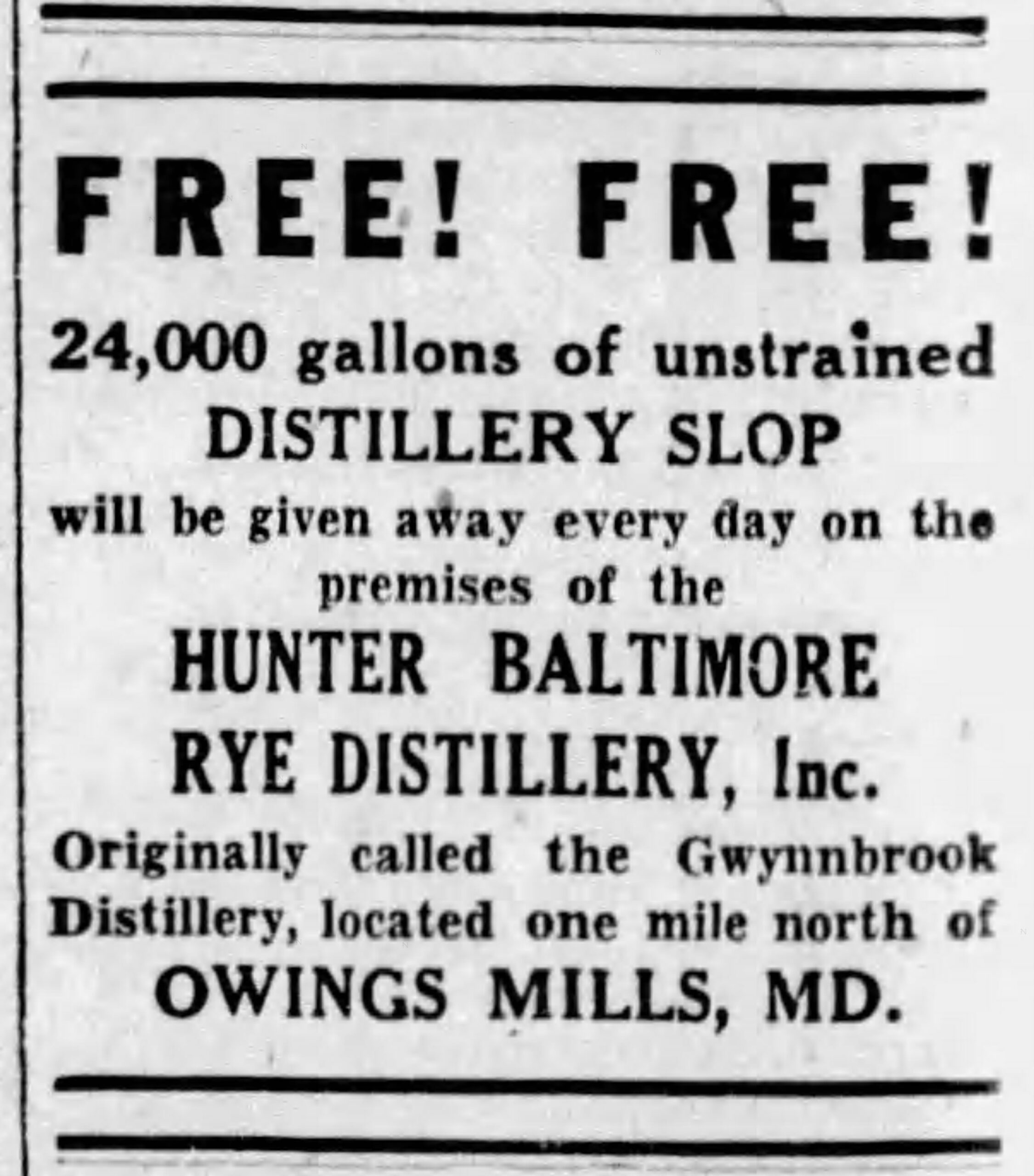

In 1934, the Gwynnbrook Distillery’s property was sold by John Roney to the Patapsco Spirits Company. The Patapsco Spirits Company had already gained control of the Hunter-Baltimore Rye trademark from the Lanahan estate, and it had plans to use the plant for distilling purposes once again. For more info on Hunter-Baltimore/Hunter-Gwynnbrook, read more HERE.

So, was Gwynnbrook important to American Whiskey History? It was one of the distilleries that distilled medicinal whiskey during Prohibition, so YES! Somehow, poor Gwynnbrook has been completely neglected and forgotten simply because IT WAS A RYE DISTILLERY. I can think of no other reason why it has been eliminated from the list of “6 distilleries that distilled and sold medicinal whiskey during Prohibition.” It may seem like I’m beating a dead horse here, but CAN WE PLEASE STOP SAYING THERE WERE ONLY 6?!! American Whiskey History is MORE THAN JUST BOURBON HISTORY. And yes, I will return to this topic again in the future. Thank you. (Rant over.)