The Wheatland Distillery

Miller & Mooney

Womelsdorf (Ryeland)

Berks County, Pennsylvania

RD# 75

1st District

There were many large-scale distilleries in Pennsylvania before Prohibition, and though most were in the western part of the state, Miller Pure Rye Distilling Company was one of the notably sized producers in the east. The distillery had a short operating lifespan in comparison to many other large Pennsylvania facilities, but that life was full of drama. The history of the distillery in Womelsdorf began in defiance of the Whiskey Trust, but ended prematurely in the wake of death and debt.

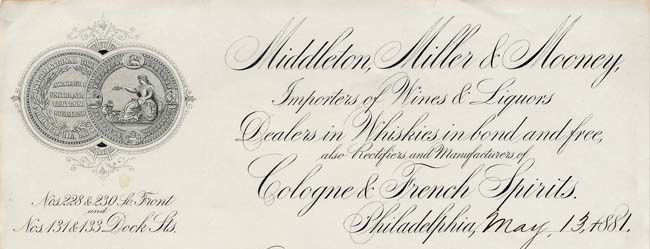

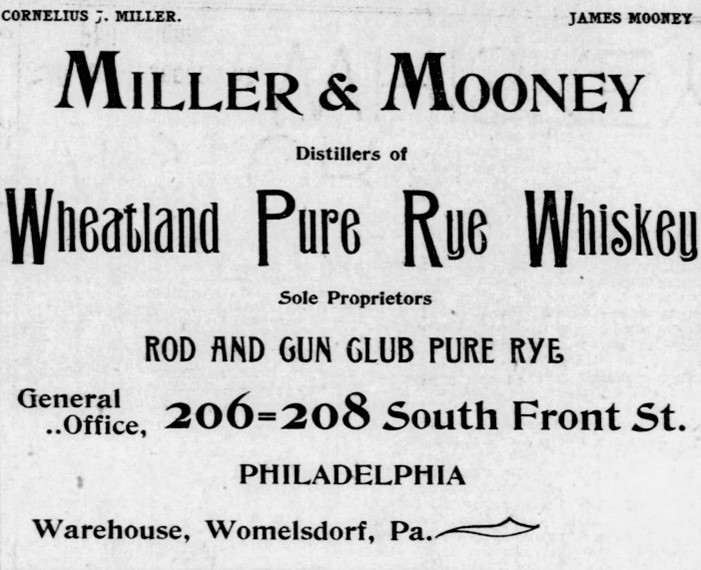

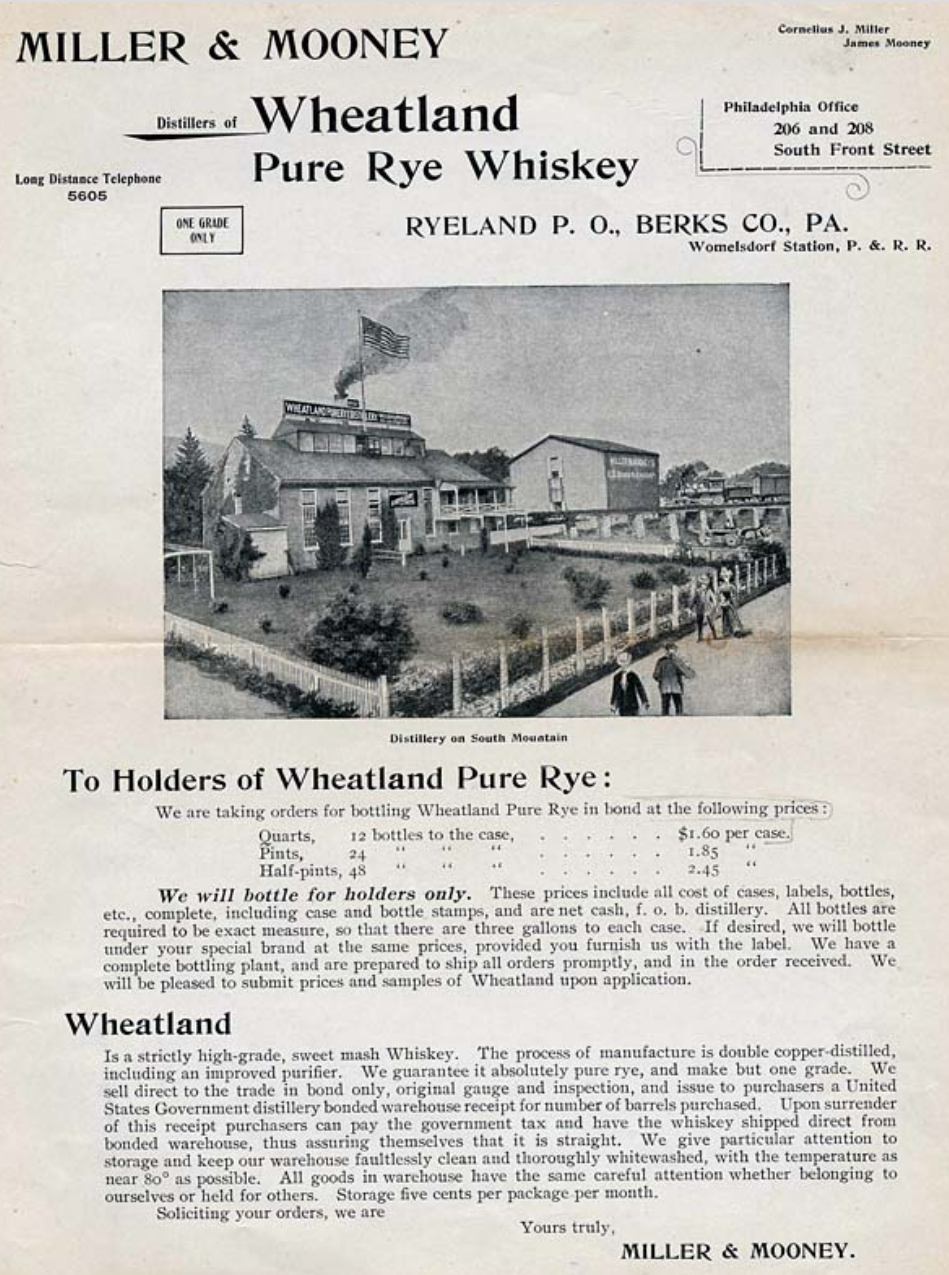

The men behind what would become the Wheatland Distillery were from an influential Philadelphia liquor firm. Cornelius J. Miller and James Mooney began their career with a business partner named George W. Middleton at the firm of Middleton, Miller & Mooney. They were located at 228-230 South Front Street, Philadelphia. Their letterhead described them as “Importers of Wines and Liquors, Dealers in Whiskies in bond and free, also Rectifier and Manufacturers of Cologne and French Spirits.” The description is telling because a “rectifier and manufacturer” did not produce spirits crafted in their own distillery. Instead, they redistilled, blended, or altered spirits that were purchased in bulk from privately owned distilleries and, from those sourced products, bottled their own signature brands. By 1884, the firm of Middleton, Miller & Mooney was dissolved, with Miller & Mooney striking out on their own. George Middleton remained in the company’s original location at 228-230 S.Front Street, while Cornelius and James moved their new offices a few doors down to 206-208 Front Street. It may seem a bit odd that they chose to remain neighbors, but Front Street in Philadelphia was lined with competitive liquor firms that all wanted to be next to the Delaware Riverfront’s piers and the River-front Railroad*, which had just been completed. Now here’s where it gets interesting…

Figure 10- Middleton, Miller & Mooney letterhead, 1881.

Over the next decade, C.J.Miller and James Mooney distinguished themselves among the many influential liquor traders and firms in Philadelphia. Their growth timeline in Philadelphia, however, was unfolding simultaneously with that of the Distilling and Cattle Feeding Trust in Peoria, Illinois. The Whiskey Trust, as it was known, was one of the largest and most notorious combines in the industrial history of the United States. Its efforts to limit spirits production, control pricing, and monopolize the rectified liquor trade undermined the success of powerful liquor firms in the eastern cities. Philadelphia firms staunchly opposed the trust’s five cent rebate regulations in 1890, protesting the move as tyrannical and illegal.

Officers of the Whiskey Trust agreed to give participating wholesalers a rebate of 5 cents on the gallon 6 months after the date of purchase, with the proviso, however, that the customer would only purchase their goods from the trust. Meanwhile, a concerted movement by liquor firms to oppose the Whiskey Trust was gaining strength in Philadelphia and New York. Cornelius was quoted on June 17, 1890 by The Times of Philadelphia as saying, “We are certainly being treated unfair, but what can we do about it? The trust practically controls the spirit supply, and they are in such a position that they can withhold it from us if they so desire.” At this point, powerful Philadelphia firms began to meet and discuss their options. Angelo Myers, as a representative of the powerful firms of Philadelphia met with competitive interests in New York, and together, they agreed the best way to fight the trust was to build their own distilleries and control their own production. Miller and Mooney must have agreed with the scheme because they were one of 3 major distilleries to be built in 1892 near Philadelphia.

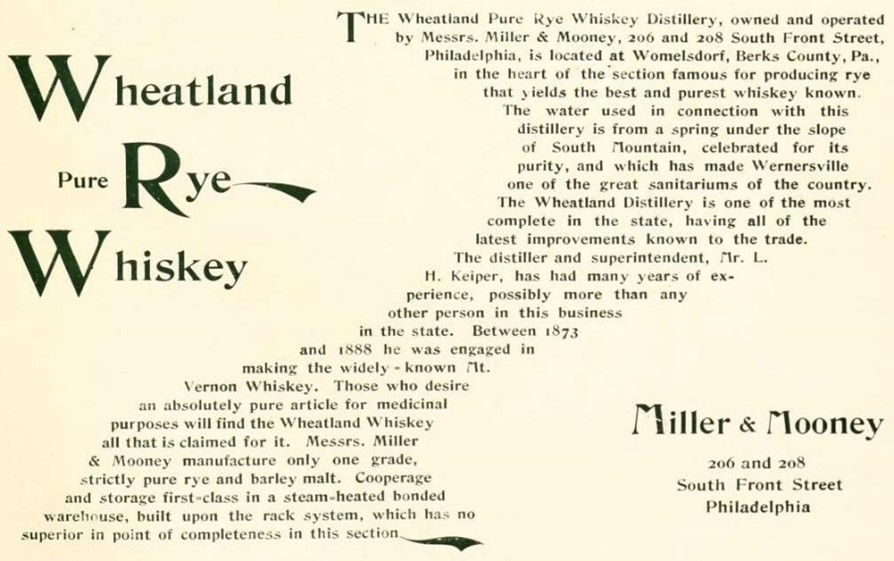

Philadelphia advertisement, 1893.

The Allentown Leader (Allentown, Pa.), October 30, 1895.

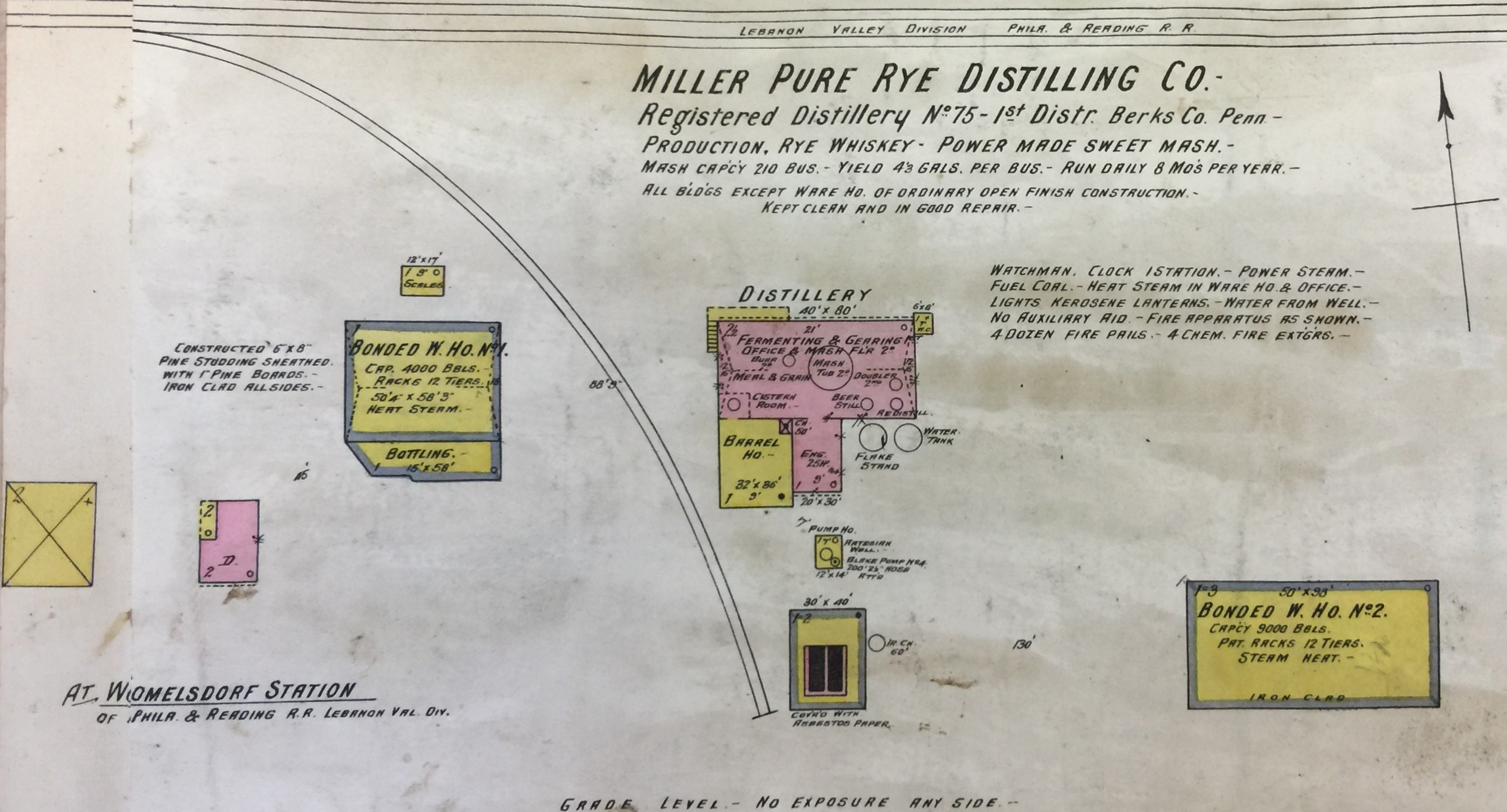

On May Day, 1893, the Wheatland Distillery went into operation. Miller and Mooney built their new distillery in Womelsdorf, Pennsylvania, the heart of Berks County’s rye farming region. The water for the distillery came from a famously pure water source beneath South Mountain. In fact, sanatoriums were springing up all around the area that offered restorative water-based treatments for the wealthy families of Philadelphia society. Miller & Mooney hired L.H.Keiper, an experienced distiller who made the famous Mount Vernon Rye Whiskey for the Hannis Distilling Company from 1873-1888, as their superintendent and on-site distiller.** No expense was spared to put all-new, modern distillery equipment in place. They installed 2 stills: one wooden grain still with a capacity of 800 gallons and one 500-gallon copper still, both heated by steam. There was a copper separator and copper doubler**** above, on the 2nd floor. Wheatland had its own cooperage and bottling house. The steam heated, iron clad bonded warehouses held racks of up to 4000 barrels in the first and 9000 barrels in the second. Miller and Mooney advertised themselves as being “one of the most complete in the state, having all the latest improvements known to the trade.” Everything seemed to be running smoothly…until 1902.

Sanborn Insurance Map, Miller Pure Rye Distilling Co. 1894 with amendments made in 1904.

The Miller Pure Rye Distilling Company was organized as a Delaware based corporation in on April 21, 1902 by Miller and Mooney.*** Later that year, James Mooney died, leaving his executors and trustees as the major stockholders still partnered with C.J. Miller. The following January, C.J.Miller organized the Miller Pure Rye Distilling Company into a domestic corporation of Pennsylvania called the Pennsylvania Company. Just 6 months later, the distillery and its stock went up for sale and Siegfried V. Nagel agreed to purchase the distillery for $90,000, paid for in monthly installments. Almost immediately after purchasing the company, Nagle created his own corporation called the Miller Pure Rye Distilling Company in New Jersey. For the next few years, S.V.Nagel went about his duties at the distillery, performing all the on-site duties of an owner with the consent of C.J.Miller. That all changed dramatically on February 15, 1905 when Miller discovered that Nagel had been failing to make payments and had him forcibly kicked off the property with a squad of men. This action kicked off 2 years of nasty lawsuits and arguments disputing which iteration of the company (New Jersey or Pennsylvania/Delaware?) was legally able to secure the plant’s distilling license. The men finally settled their dispute with decisive ownership being granted to Nagel. This, unfortunately, was not the end of the lawsuits involving the distillery. Nagle was in big trouble…

Philadelphia saloon keepers and customers were demanding thousands of dollars in product with balances due. Lawyers were hounding Siegfried. It soon became clear that Nagel had been swindling between 75-100 Philadelphia saloon keepers into purchasing stock in his New Jersey corporation which was found to be nearly worthless. He had been deceiving the banks and creditors by using the authority of his interim position at the distillery. The debts he accumulated exceeded $50,000, and Nagel was in no position to settle them. On December 3, 1907, Siegfried V. Nagle shot himself in the head in his office at the Bourse Building in Philadelphia. The revolver he used was found by his side. Papers were littered across the office, but a simple note was found on his desk that read, “Tell Mart.” Martin S. Filbert was the company secretary and Siegfried’s close friend.

The lawyer for the Miller Pure Rye Distilling Company made a statement assuring their creditors that everyone would be repaid. The assets of C.J.Miller’s Pennsylvania Company amounted to about $50,000, while the plant itself was worth about $55,000 and the 2,000 barrels of whiskey in the bonded warehouses were valued around $40,000. Everything began to be sold off, starting with the bonded whiskey. Unfortunately for some of the owners of bonded whiskey that had been sold to them by Nagle, their barrels would be held up by the courts for years. The distillery itself (no whiskey included) was sold for $7,500 to William A. Schwenk, an extensive coal operator from Schuylkill County and a creditor of the plant, to the amount of $40,000. Cornelius Miller died after the company’s bankruptcy, and his heirs fought over his estate and the whiskey barrels, whose ownership was still in question.

The Miller Pure Rye Distilling Company became known to the locals during its idle years as just “the Womelsdorf plant”. Thieves were caught stripping copper pipe and kettles from the building in 1918. Once Prohibition took hold, the distillery was sold to Standard Chemical Works. They would utilize the four large, existing buildings, and would erect 3 more to mass manufacture insecticides. One of the finest Pennsylvania rye whiskey distilleries in the late 20th century would become of the largest poison producing plants in the United States.

*Last rail of the River Front Railroad was laid on Delaware Avenue in March of 1882. It completed the railroad connection made between the Pennsylvania Railroad tracks at Greenwich point (and the tracks of the same road) and the Reading Railroad at Kensington and Port Richmond. The new rail line along Delaware Ave between Front Street and the Delaware River connected all the major rail lines to the riverfront piers. The Philadelphia Belt Line Railroad (PBL) was created in 1889 with the purpose of allowing any Philadelphia railroad to have access to the Port of Philadelphia. The railroad was used as a way to fight the railroad empire of the Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR), trying to bring other railroads to gain access to the Philadelphia waterfront via a right-of-way that PRR not yet taken.

** Hannis Distilling Company’s office was in Philadelphia, and it is likely that they came to know of Keiper’s availability through all the meetings held with other anti-trust firms.

*** 1901 was an impactful year for Pennsylvania distilleries in that the McClain Corporation Bill was finally signed into law by Governor Stone. For the first time, distilling companies, which had previously been barred from forming corporations, were now free to do so.

****A separator was a piece of equipment that was monitored by a distillery worker (usually through a sight glass) which could direct distillate into to the cistern or back into the still for redistillation. A doubler is a pot still used for the “second distillation” or refinement of distillate produced by the beer still.