The following is a series of 7 (long form) posts- all posted on Facebook between June 9th and 15th, 2024.

Schenley. An Intro.

Part 1

Schenley. What’s in a name?

Part 2

Part 3

“S.W. Sinclair, of New York City, was in McKeesport yesterday looking for a site on which to build a distillery. Mr. Sinclair was in McKeesport some years ago on a similar errand and was much surprised to find that McKeesport had grown so large. It is expected that a building will be commenced in the spring.”

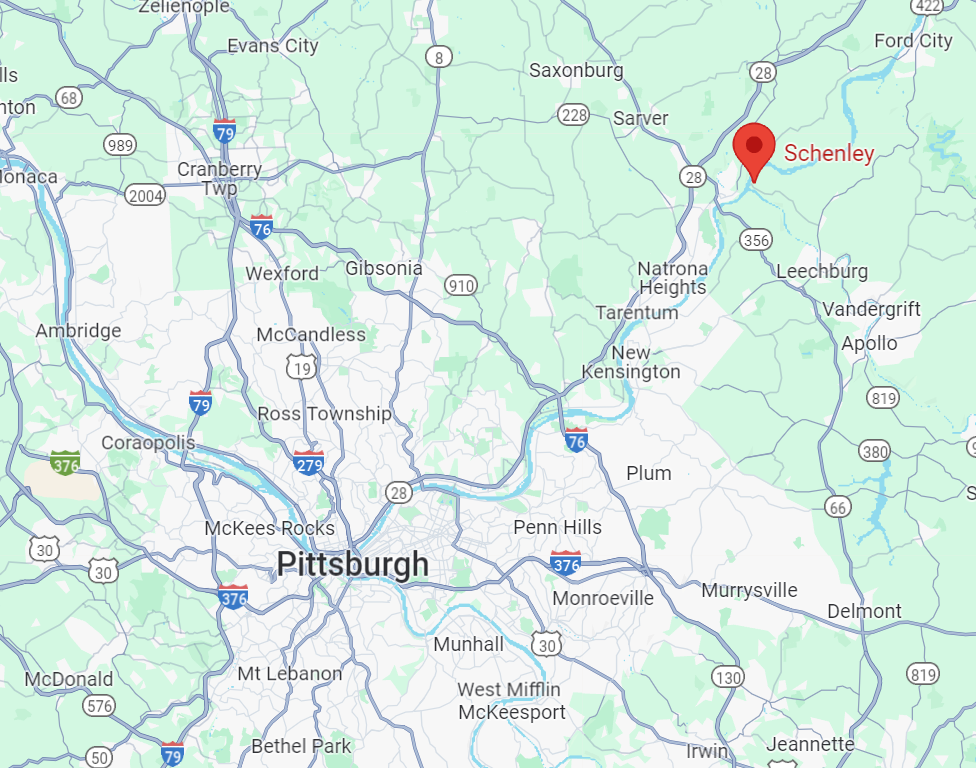

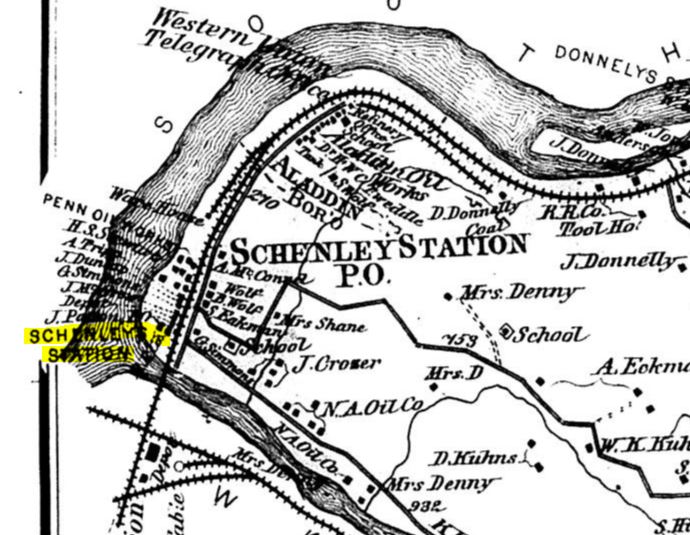

“Chemist Frank Sinclair found an underground stream above the junction of the Kiskiminetas and Allegheny Rivers in Pennsylvania. With his charcoal expertise, Sinclair concluded that this stream water was ideal for making whiskey. He acquired the land from Mary Schenley and with his brother Harry Sinclaire & Henry Bischoff, began what later became known as a Schenley distillery.”

(Armstrong County, Pennsylvania. Her people, Past and Present, 1914.)

The distillery was no small thing. We’ll look at specific details about the distillery itself tomorrow.

Schenley. The Original Distillery…Until Prohibition.

Part 4

It’s important to note that Schenley Distillers Limited was not the only distillery being built in 1892 by liquor men that wanted to be free of the price gouging and oppressive tactics being foisted on the industry by the Whiskey Trust. The distillery needed to manufacture enough whiskey to satisfy market demand for their products, so its construction was ambitious in scope. A 30,000-bushel capacity grain elevator was built beside the tracks of the Allegheny Valley Railroad to easily receive bulk grain shipments. An iron-clad barrel house was placed beside the grain house for barrel delivery and branding. The still house was 4 stories tall: Gearing and the beer well were on the ground floor; The beer still and doubler, yeast room, mash floor, and grain mill (with double rollers) were on the 2nd floor; Ground meal storage, scales, and a laboratory were on the 3rd floor; Cleaned grain was received and sifted (before being loaded into the hopper and gravity fed to the mill below) on the 4th floor. The distillery’s capacity began operations at 200 bushels mashed per day and was run on a daily schedule for 10 months of the year. The still house was surrounded by three single story additions: A fermenting house with 14 fermentation tubs, a cistern room, and a large boiler house. The property also included a modern drying facility to convert spent mash into dried cattle feed. Both cattle and fowls were raised on site. The two original bonded warehouses were soon joined by another pair of warehouses just a few years later; Warehouse 1(A) was 50’ x 82’, 4 stories, and held 4500 barrels; Warehouse 2(B) was 98.6’x100’, 5 stories tall, with 15 tiers of patent racks holding 12,000 barrels; Warehouse 3(C) and Warehouse 4(D), which were added in 1903, were identical to 2(B). Each 5-story warehouse had a rope and pully hoist with an engine that helped to load barrels into the buildings. All warehouses were steam heated. The distillery had a private water system that could draw water from the Allegheny River or from deep wells below the building. In the 1900 census, Frank is listed as a “distillery manager”, Henry Bischoff is listed as a “distiller”, and Harry as “salesman” for the company. (Thomas R. Sinclaire is listed as “retired”.)In 1903, the investment of new capital fueled the facility’s expansion, bringing the facility’s mashing capacity from 200 to 500 bushels per day and prompted the partners to change their firm’s name to the “Schenley Distilling Company”. The company was nearly a decade into production and the future looked bright! Unfortunately, the distilling industry is riddled with tragedy, and Schenley’s distillery was no exception.

Schenley. A Company Built to Withstand the Whiskey Trust Loses Its PA Roots…And Finds Its Corporate Future, Ironically Through the Trust.

Part 5

1918. Thus ends Schenley Distillery’s connections to its founders.

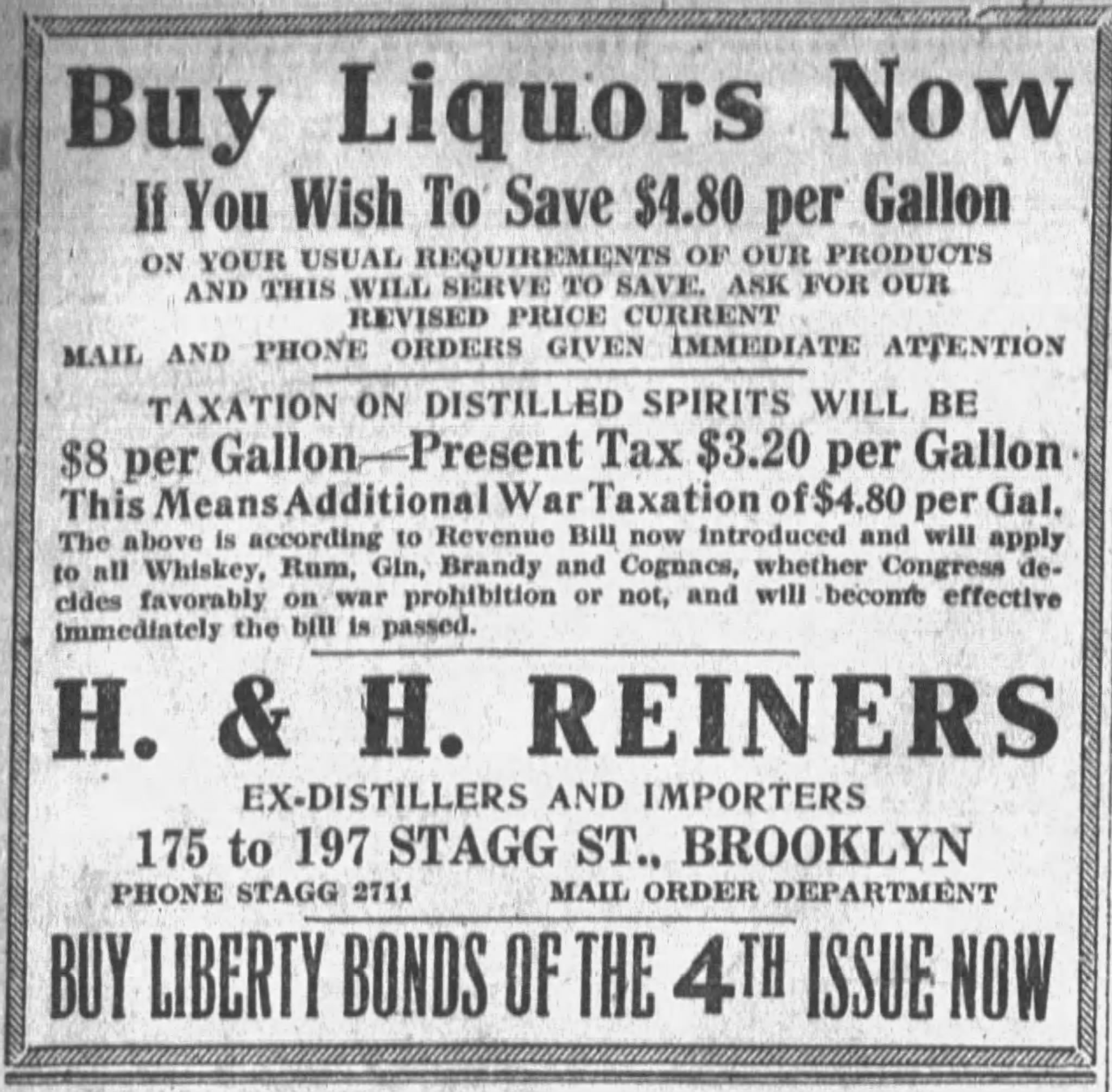

“Mr. Bischoff started his business career with the Reiners concern as a boy and eventually became its head. He then decided to enter the distilling business and founded the plant at Schenley, Pa., which continued until the advent of prohibition. The firm then was sold. It had no connection with the present Schenley Distillers Corporation.” (The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, May 9, 1941)

That last sentence is telling. One can only imagine how frustrating it must have been for Mr. Bischoff to watch the company he built thrive in the hands of another man without any recognition whatsoever.

Schenley. The Warehouse Loophole.

Part 6

The first few years of Prohibition saw Lew Rosenstiel buying and selling whiskey through his and D.K.Weiskopf’s holding company, the Schenley Products Company. One of Rosenstiel’s notable early sales took place in 1923 when Rosenstiel moved a large quantity of whiskey that he purchased several years earlier from the Midway Distillery, otherwise known as the S.J. Greenbaum Distillery. The whiskey was all privately owned, but it was being stored in Rosenstiel’s warehouses and its owners were delinquent in paying their storage fees. (Honestly, who could blame them with Prohibition turning their investments into financial burdens.) Section 33 of the Act of March 11, 1909 stated warehouse owners could recoup losses from delinquent storage payments by selling off privately owned property within their warehouses as long as the owners were first informed of the sale. After the Concentration Warehouse Act of 1922, many legal notices (like the one attached below) began showing up in newspapers. Long, itemized lists of whiskey stocks were published in newspapers across the country to give private owners a “fair” 10 days’ time to settle their debts and reclaim their whiskey before the auction date. Usually, when you come across a long list of whiskeys in a newspaper under the heading “Legal Notice”, you can assume that the warehouse company listed planned to purchase all that whiskey outright through its own auction and relocate everything to a secure concentration warehouse of their choosing- usually their own. In Rosenstiel’s case, he had nowhere to put any of his whiskey because he had failed to secure a coveted concentration warehouse permit! His consolidated liquor stocks that were sitting idle in his warehouses in Schenley needed a legal loophole…and Lew Rosenstiel had finally found one in Pittsburgh.

By 1924, the owner of Joseph Finch Distillery (Sol Rosenbloom) sold the distillery and its concentration warehouse permit to Schenley Products Company.* The permit was finally in Rosenstiel’s possession, and he was able to transfer the Joseph Finch Distilling Company’s name and its permit to his own facility in Schenley. He hired Harry E. Wilken as his head distiller to manage the plant. The Finch Distillery in Pittsburgh was left to be dismantled. The appropriation of Finch’s consolidation permit was the move that secured Rosenstiel’s historically significant future in the liquor industry. A few years later, he secured 240,000 cases of Old Overholt Pure Rye Whiskey and 120,000 cases of Large Pure Rye Whiskey, two of the largest purchases of whiskey during the Prohibition era. Five years after taking control of Joseph Finch, Rosenstiel purchased the George T. Stagg distillery in Frankfort, KY. With twice the output capacity of Joseph S.Finch (Schenley), the purchase of Stagg was significant. At the time, Schenley was one of four locations in Western Pennsylvania where bonded liquor was being stored. The federal government, concerned about the likelihood of illegal raids, devised and installed a “tear gas” protection system to thwart thieves.

When the American Medicinal Spirits Company was organized in July 1927 to consolidate disorganized units competing for the liquor trade, they offered Schenley Products Company the opportunity to merge. Rosenstiel refused and set his sights on expansion. As the “Roaring 20’s came to an end, the government’s medicinal whiskey stocks had dwindled and the need to bring distilleries back online became a possibility. By 1930, Rosenstiel was in a perfect position to be granted a permit to produce 600,000 gallons of medicinal rye whiskey.

More on this tomorrow.

*Why the heck would Sol Rosenbloom, the world’s largest liquor distributor in the late 19-teens, sell Joseph S. Finch and Company to the Schenley Products Company you ask? Good question! Rosenbloom was leasing the property from the Pontefract trustees (Elizabeth and John Walker). They consented in writing on March 1, 1916 to transfer its lease to Sol Rosenbloom. When Rosenbloom took over, there remained almost 9 ½ years on the lease. In 1917, the US government shut down distillery production across the country and Rosenbloom began to see that the burden of taxes on the 50,000 barrels still in the warehouses at J.S.Finch and Co. were unsustainable. He still believed that liquor dealers like himself would be saved by an eleventh hour move of the government to halt the implementation of Prohibition. But to be safe, on January 2, 1920, he quickly loaded train cars with whiskey from his S. Rosenbloom & Co. warehouses in Pennsylvania and Kentucky and sent them to Atlantic ports where he had ships waiting. The deadline to transport liquor out of the country was January 5th. He planned to transport half a million gallons of whiskey worth over $15 million to Germany, France, Bermuda, Cuba and Canada. After Prohibition went into effect, Rosenbloom made plans to liquidate his business. Part of this liquidation was selling the permit he secured and the whiskey that remained at J.S.Finch to Lewis Rosenstiel. If it weren’t for Sol Rosenbloom’s choice to transfer his permit and get out of the liquor business, Schenley as we know it would not have existed.

As a side note and an admission of bias, my favorite pre-Pro distillery in Pennsylvania was the Finch Distillery. The fact that Rosenstiel left it to be dismantled and tossed all that history to the wind is tragic. It is also why I do not see Rosenstiel as a great hero of American whiskey, though he is an incredibly interesting and pivotal historic figure. He was an incredibly savvy businessman that made a great deal of money during a unique time in American whiskey history. But, as I said, more on this tomorrow!

Schenley. Post Repeal.

Part 7, the finale

It’s too much to get into Rosenstiel and Schenley Product Company’s efforts to bottle their medicinal whiskeys during Prohibition. Suffice it to say that Schenley, with its large stocks of whiskey secure in its warehouses, bottled that whiskey, regardless of its provenance, under its own labels. With a bit of sleuthing and research, one could study the back labels and tax strips of surviving bottles belonging to Schenley’s medicinal whiskey brands (Golden Wedding, Stagg, OFC, etc.) and discover who actually made the whiskey within. In most cases, it was not Schenley. What’s important is that Rosenstiel, with his foot in the door as a concentration warehouse owner, was a shoo-in for consideration by the Treasury Department to receive a license to distill whiskey in 1929. The Schenley plant was dusty and shuttered, but it was intact, which was more than could be said for most of the distilleries in the United States. In 1930, it was one of four plants assigned to manufacture 700,000 gallons of rye whiskey to replenish dwindling medicinal whiskey supplies for the US. The rye distilleries chosen for licenses were:

- Schenley Distilling Co.

The plant in Schenley was operated as the Joseph E. Finch Distilling Co. - Large Distillery

This distillery had been active from 1920 to 1922 and was an unofficial concentration warehouse with 20,000 gallons of whiskey stored that had been produced during those years. - A.Overholt & Co. at Broad Ford

- Baltimore Distilling Co.

This distillery was owned and operated by the American Medicinal Spirits Company.

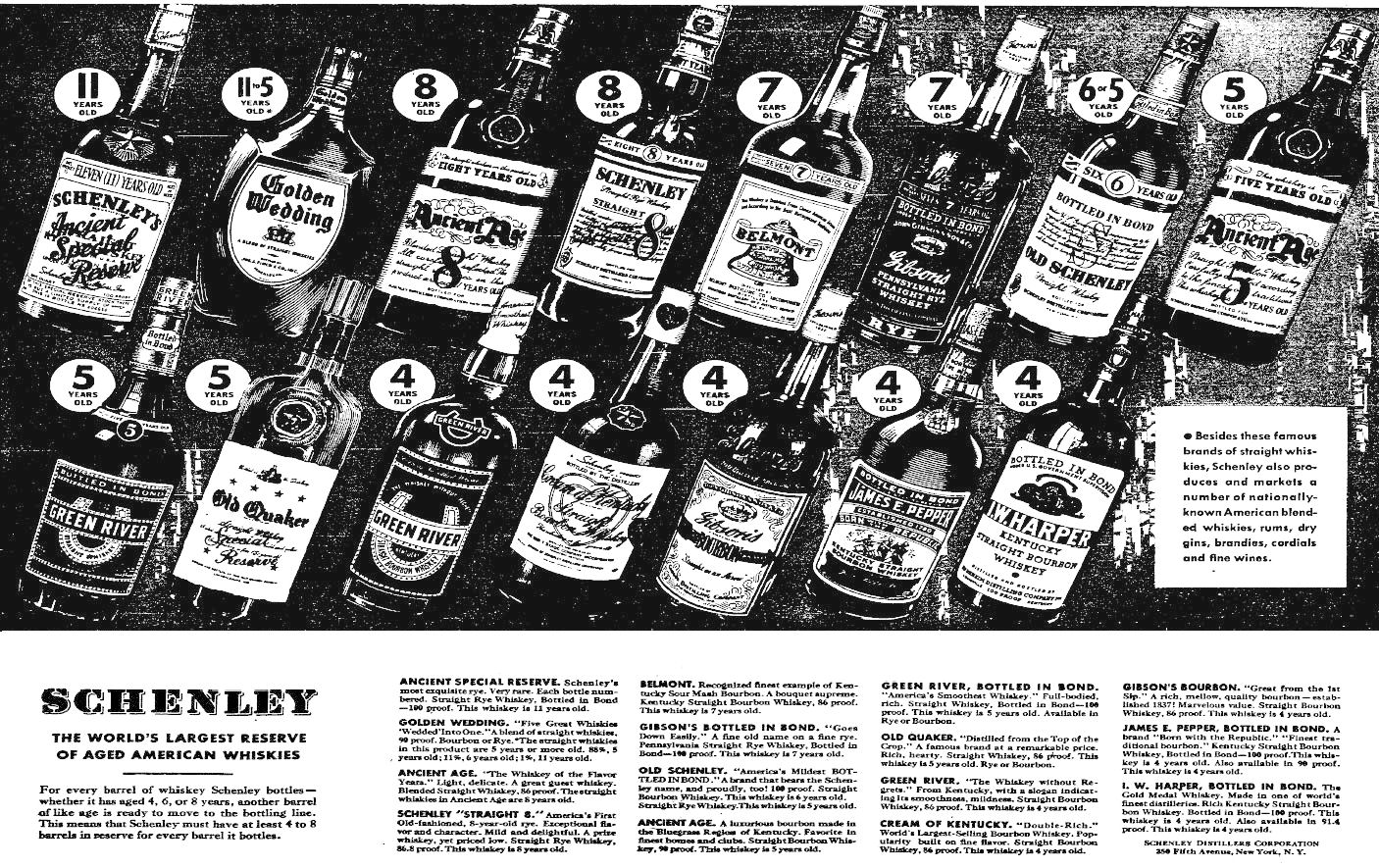

Just before Prohibition was lifted, the Schenley Distillers Corp. was incorporated in Delaware on July 11, 1933, with executive offices at 350 Fifth Ave., New York. It functioned as a holding company until September 30, 1938, when New Jersey based Schenley Products Co., Inc. was dissolved. While Schenley Products Company had been functioning as the operating company when it was absorbed by Schenley Distilling Corp., the latter took on its functions as well as its assets. After Repeal, Schenley was one of four companies, which later came to be later known as the “Big Four”, that owned 72% of the aging whiskey stocks in the United States over 4 years old. 22 companies produced 90% of the nation’s liquor in 1934. Schenley operated 5 of those 22 plants, and they, alone, produced 15.84% of America’s whiskey. The company was the second largest producer in the country, second only to Sam Bronfman’s J.E. Seagram’s. Those 5 were Joseph S. Finch & Co. (aka the Schenley Distillery) in Schenley/Aladdin, Pa., George T. Stagg in Frankfort, Ky., Old Quaker Co. (W.P.Squibb) in Lawrenceburg, Ind., James E. Pepper Distillery in Lexington, Ky., WHO IS THE 5TH?

Outline of acquisitions from 1933-1943:

July 1933- The entire capital stock of Schenley Products Company

July 1933- W.P. Squibb Distillery Co. acquired. The distillery in Lawrenceburg, Indiana was refurbished and re-established as the Old Quaker Co. (Schenley subsidiary) on November 20, 1933.

July 1933- assets of James E. Pepper & Co. The dismantled distillery was refurbished. It was re-established and began operations on October 25, 1934.

1935- The New England Distilling Co. (est. 1885) was acquired by Schenley Products Co. Schenley Distillers Co. absorbed the company on Sept. 30, 1938

January 1, 1937- Bernheim Distilling Co. acquired (stock acquisition). Bernheim applied for and was granted an amendment to its distillers permits, amending its name to “also doing business as Shaw’s Pure Malt Distilling Co., also doing business as Kentucky Par Distilling Co., also doing business as I.W.Harper Distilling Co., also doing business as Robert Morris Distilling Co.”

May 22, 1940- assets and business of Oldtyme Distillers Corp.- This corporation operated much like Schenley with a holding company (Oldtyme Distillers Corp.) and an operating subsidiary (Oldtyme Distillers, Inc.). The operating subsidiary owned Monticello Distillery Co. in Cedarhurst, MD and Kentucky Valley Distilling Co. in Limestone Springs, KY. Schenley acquired these assets with their purchase of Oldtyme Distillers for $5,935,335. In 1944, the name Oldtyme Distillers was changed to Three Feathers Distributors, Inc.

January 6, 1941- Cresta Blanca Wine Co. (Livermore, Calif.) acquired through stock by Schenley Import Co. (Schenley subsidiary) for $299,362.33. A corporation under the same name was established in Delaware to operate the company and several other wineries.

May 1941- inventories of bulk whiskeys, trademarks, and good will of Merchants Distilling Corp., a case goods business, for $3,600,000.

July 1941- assets and business of John A.Wathen Distillery Co.- Wathen was a Missouri based corporation that rebuilt the Wathen Distillery after 1934. Within a few months, the property was transferred to George T. Stagg Co. (Schenley owned) and then to Associated Kentucky Distilleries Co. in Oct 1941.

November 1, 1941- assets and business of Buffalo Springs Distilling Co. in Stamping Ground, KY. This distillery operated under the name Green River Distilling Co.

September 18, 1942- assets of Colonial Grape Products, Co. in Elks Grove, CA. Proprietorship was transferred to Cresta Blanca Wine Co., Inc (Schenley owned)

Sept. 21, 1942- Pan American Distilling Co. acquired through stock purchase.

October 1941- Dubonnet, Inc., a wine blending house, is incorporated as Dubonnet Corp, Inc. Schenley becomes owner of all class A stock and Dubonnet Wine Corp. retains all class B stock. A rectifying house and bottling plant are operated in Philadelphia, PA and a winery in Lodi, CA.

November 16, 1942- Roma Wine Co. in California acquired for $6,400,000. In January 1943, Roma Wine Co, Inc. was incorporated in Delaware.

November 24, 1942- assets of Central Winery, Inc. for $3,800,000. (2 bonded wineries and one fruit distillery) Their St.Helena, CA property was managed by Cresta Blanca Wine Co., Inc. (Schenley owned). Their Kingsburg, CA were operated by Roma Wine Co.,Inc. (Schenley subsidiary)

November 28, 1942- Blue Ribbon Distillers Co. was acquired by Bernheim Distilling Co. (Schenley subsidiary) Proprietorship was transferred to George T. Stagg (Schenley owned) the following month.

December 1, 1942- George Benz and Sons, Inc., a Minnesota rectifying plant and warehouse, acquired by stock purchase for $5,500,000.December 1942- L.E.Jung & Wulff Co. of Louisiana. The assets were transferred to the Steinhardt Co.,Inc. (Schenley subsidiary) which changed its name to L.E.Jung & Wulff Co., Inc.

December 15, 1943- Blatz Brewing Co. (Wisconsin) acquired for $6,000,000.

World War II brought rationing and a call for distillers to transition into making industrial alcohol for the war effort. Schenley’s J.S. Finch plant operated throughout the war making industrial alcohol for the war effort. They even made penicillin at their Old Quaker facility in Indiana for commercial distribution. SchenLabs Pharmaceuticals, Inc., whose creation was largely due to a new post-war marketplace, was incorporated in Delaware in 1945 (trademarked in 1959). Schenley Distillers Corp. continued to acquire new and more diverse assets as the market adapted and fluctuated. Schenley Industries was born from the old company in 1949.

Lewis Rosenstiel, the man that made the Schenley Distillery an internationally recognized household name, retired in 1968, selling his interest in his company to the Glen Alden Corporation. He died in 1976. Schenley’s long and complex history finally came to an “end” when it was sold to National Distillers in 1987. It was 5 years short of the company’s distilling legacy reaching its centennial (100 years old). The Joseph S. Finch Distillery in Schenley continued to make whiskey for Schenley Distilling Corp. until the mid-1970s. It then transitioned into a highly automated and modern packaging plant for many different products: whiskeys, bourbons, Canadian whiskey, scotches, gins, tequilas, and rum. Some of their brands were Schenley Reserve, Schenley Gin, Schenley Vodka, Coronet Brandy, Canadian MacNaughton, Grande Canadian, J.W.Dant Scotch, Cruzan Rum and Ole Tequila, all of which were available at Pennsylvania Liquor Stores in the late 70s and early 80s. The plant covered 60 acres stretching along the Allegheny River through Schenley and Aladdin. It employed 400 people with a $4,000,000 payroll. Its federal, state, and local taxes amounted to $105,000,000 in 1975.

Hope you enjoyed the write up! Cheers! That said, I may need a day off…