The Frost family of Western Pennsylvania were acclaimed master distillers of Old Monongahela Pure Rye Whiskey in the late 19th and early 20th century. The patriarch of this family of distillers in America was James Frost, Jr. James emigrated from London, England to the United States in 1869, settling first in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. His parents, James Frost, Sr. and Eliza (Weller) Frost left him an orphan at a young age, forcing James to take his future into his own hands.

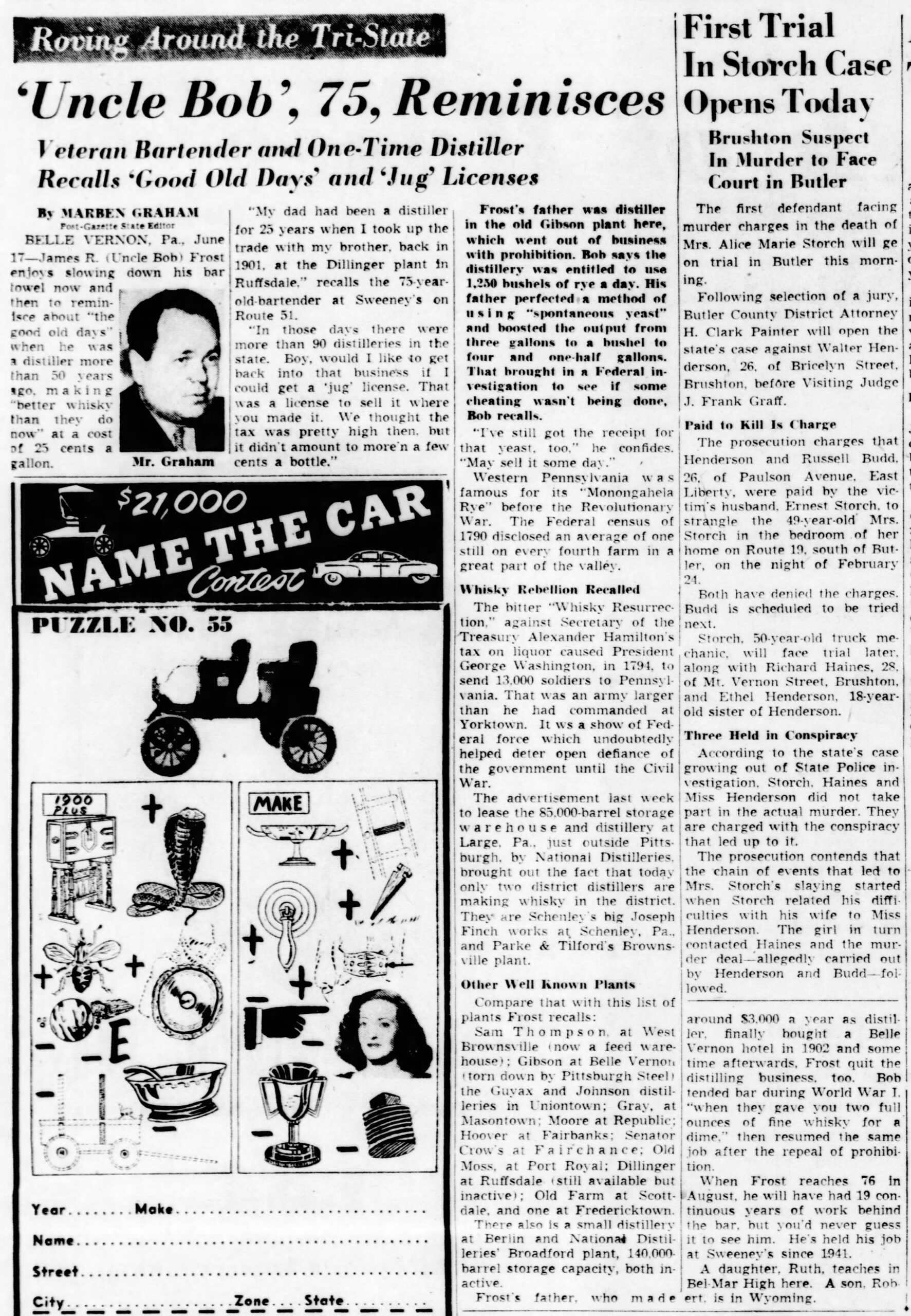

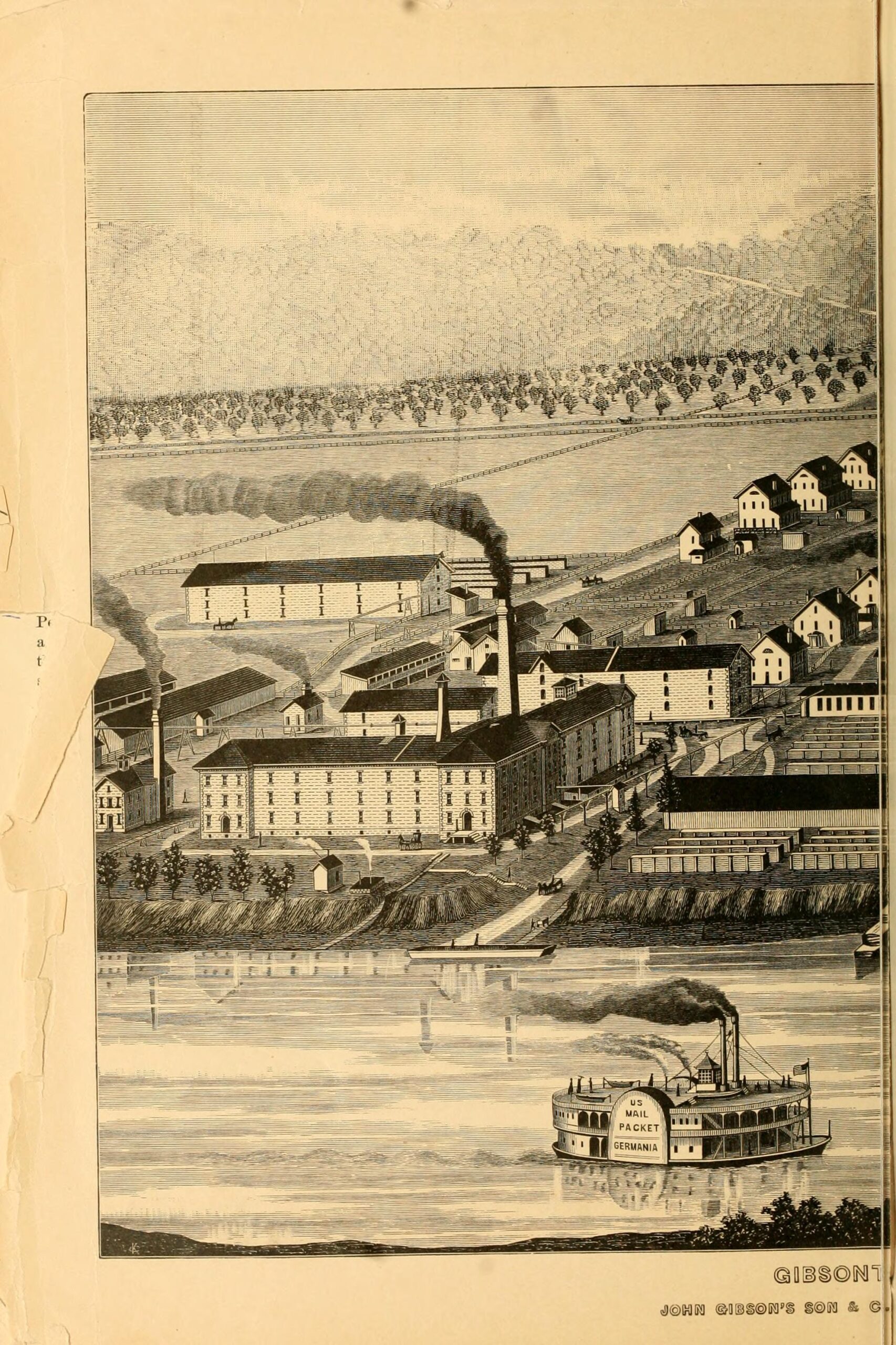

After a year of taking what jobs were available to him in Pittsburgh, James was hired by John Gibson’s Son & Company, most likely by Thomas L. Daly, Sr. (the plant’s superintendent since 1857). By 1870, John Gibson’s distilling plant in Gibsonton Mills had been actively distilling rye, wheat, and bourbon whiskeys for 13 years and had grown to become the largest manufacturer of whiskey in the world! James’ appointment was no small thing…though that may not have been apparent at the time. Though John Gibson passed away 5 years before James was hired, Mr. Gibson chose the site for his distillery and made plans for its future with purpose. He built on the site of a much older distillery with deep roots in Pennsylvania whiskey-making. The previous owner of the land, Noah Spears, was grandson of Henry Spears. (The log cabin in which Henry died remained on the distillery property near the residence of Thomas L. Daly until about 1880.) Jacob Spears, also grandson to Henry, was a pioneer settler of Kentucky and the founder of the Spears family in that state. (Suffice it to say that Jacob Spears was an important figure in KY distilling history. I wonder where he learned to distill? Wink wink ) While it’s difficult to know how James Frost, Jr. acquired his job at the historically significant Gibson plant, his marriage to Miss Mary Ann Johnson in 1872 may provide us with some insight. (Stay with me as I connect some dots…)

Mary Ann (Johnson) Frost’s entire family (both mother and father’s side) were involved in the cooperage industry. Mary’s father and brothers had been working as coopers in Greensboro, Pa (Greene County). The town of Greensboro on the Monongahela River is just a few miles south/upriver from the famous, though long-forgotten, distillery of Captain William Gray. (William Gray is the only distiller I have ever seen listed as “Master Distiller” on the US census.) It is likely that James Frost’s job at the Gibson Distillery created the opportunity for his and Mary’s paths to cross through James’ interaction at work with barrels- and with their coopers (Mary’s family members). In 1872, the year that Mary wed James, James relocated from Belle Vernon in Fayette County to Greene County- about 35 miles south. The couple’s decision to relocate may have been their own, but it was more likely work related. It seems likely that Henry C. Gibson (son of the company’s founder, John Gibson) sent James to Monongahela Township to hone the young man’s distilling skills with Capt. William Gray. It is quite likely that the Gray Distillery had been a favored supplier of Old Monongahela Rye whiskey for John Gibson’s liquor firm in Philadelphia long before the company built their distillery along the Monongahela River! (John Gibson had been sourcing rye from Western PA since the 1830s but didn’t build his distillery until 1853.) Gray may have even inspired the location chosen by Gibson on which to construct his giant distillery. As an older master distiller of rye whiskey, William Gray earned an excellent reputation for whiskey making in the region but would never have been able to supply John Gibson with the amount of whiskey needed to satisfy the growing demand for it in Philadelphia. Henry Gibson may have wanted his new hire to learn all he could from Captain Gray with the intention of bringing that expertise back to Belle Vernon. Whatever the reason for their move, James and Mary would spend 8 years in Monongahela Township. They lived with Ellis Johnson, Mary’s father, while James trained as an apprentice with both William and Robert Gray. At the conclusion of his 8-year apprenticeship, records show that James was offered the position of distiller at the Gibson plant, which he accepted. His new position paid him around $3000 per year, the modern salary equivalent of around $100,000. James was moving up in society, and the next few years saw his comings and goings being written about in the Philadelphia newspapers.

It is quite likely that the Johnson family’s association with Gray’s Distillery gave them “an in” with the Gibsonton Distillery when it was built in the 1850s. In fact, I found that Mary’s brother, William C. Johnson, was living next door to James and Mary Frost in Belle Vernon in 1880. This implies that either William joined James to secure his own position at the Gibson distillery, or it was the other way around! What’s more, Andrew M. Moore, who had been a partner of John Gibson’s since 1852, had been a skilled cooper before taking on a leadership role at the firm. It’s not too far a stretch to believe that James’ trade skills and connections helped him to land the job at Gibsonton. Perhaps the job he was given in 1870 was not the job that James really wanted for himself. Once he put in the years of training and earned his position as distiller, however, James would spend 22 consecutive years acting as head distiller for John Gibson & Sons. During that time, he brought his own sons on as distillers and instructed them in the art of distilling sweet mash pure rye whiskey, just as William Gray had done for him.

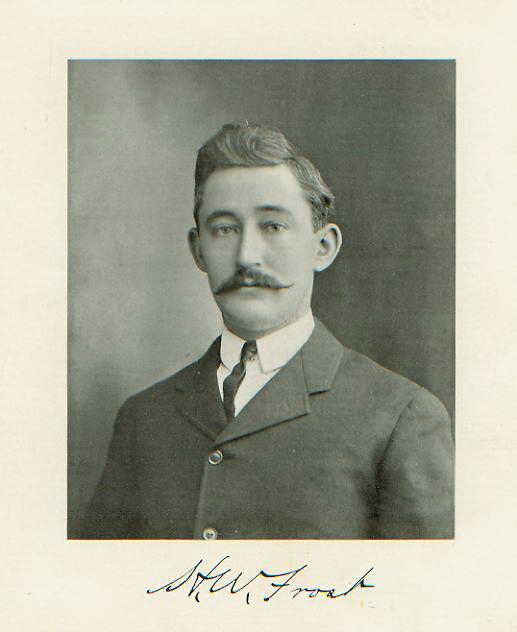

Over the next ten years, James Frost slowly introduced his sons to the trade. In 1890, however, an accident changed the fate of James’ eldest son, William E. Frost. When William was 18 years old, he “fell from a building” and “fractured his right leg so badly that it had to be amputated below the knee in order to save his life.” Needless to say, William discontinued his work at the distillery. Henry Walter Frost would join his father at the distillery two years later (1892). While the Frost family carried on in the distilling business into the early 1900s, they began to diversify their business interests as well.

In 1902, James Frost retired as master distiller at the Gibson plant and took on proprietorship of the Hotel Birmingham, the leading hostelry in Belle Vernon. He brought William along to assist him in the hotel’s management. It appears that James’ management role at the Gibson distillery was assumed by Thomas L. Daly, Jr. after his departure. That same year, Henry W. Frost was offered his own position as master distiller at the Moss Distilling Company in Fitz Henry, Pennsylvania. The job offer was with a new iteration of a much older rye whiskey company that had been on the same site. The old Moss Distillery had been idle since J.T. Moss’ death in 1894. The new Moss Distilling Co. had been incorporated in 1901 with a capital of $50,000. Its directors were James L. Delong and Charles F. Delong of McKeesport, Pennsylvania, and Robert Reinhold, Max Reinhold and David Canter of Pittsburgh. It was the second time a distilling company had ever been incorporated in Pennsylvania (due to no provisions allowing for the incorporation of distilling companies before the McClain Act) and H.W. Frost was brought on to be the man behind the whiskey. He took charge of the plant on August 1st, 1902. The following year, Henry’s younger brother, James Robert Frost, took on the role of lead distiller at the Dillinger plant in Ruffsdale, Pennsylvania.

Not to be outdone and continuing to follow in his father’s shoes, Harry opened his own hotel in Fitz Henry called the Hotel Henry in 1903. Just one year into owning the hotel, however, his wife of 6 years (Flora May Elmer) met a terrible fate when she was struck by a passing train out in front of the hotel. Harry remarried a local woman named Agnes Crilley in 1905. The couple would continue to feed and entertain locals and tourists at the Hotel Henry and would do the same at a second hotel they operated in Smithton, as well. James Frost, Jr. passed away in 1911 and would not live to see Prohibition. His sons would lose their livelihoods and their status as master distillers of rye whiskey with the passage of the 18th amendment in 1919. The family still had their hotels, but they too would lose profitability as customers left town. The distillery businesses that employed so many locals and catered to so many businesses, including the Frost family’s hotels, disappeared. The story goes that Harry and Agnes Frost’s Smithton Hotel was forced to close in 1924 after being raided by state troopers and having all of their privately owned liquor and wine confiscated. The Pittsburgh Daily Post reported that four arrests were made (though it’s not clear who was arrested) and that “four barrels of beer, 200 quarts of wine, and 15 gallons of whisky” were taken from the premises.

While the Frost family held elite positions in some of Pennsylvania’s most famous Monongahela whiskey distilleries, their legacy has been largely forgotten. There was a wonderful article in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette in 1953 where James Robert Frost was interviewed by the paper’s editor. James ‘Uncle Bob’ Frost reminisced about the good-old days and remembered his family’s years as master distillers. He was 75 years old and had spent the last 11 years tending bar at a steak house called Sweeny’s on Rt. 51 in Belle Vernon. This master distiller of rye whiskey had worked as a bartender since the first World War! The man had the recipe for James Frost’s spontaneous yeast strain and he was washing pint glasses at a roadside eatery. I’m not making fun of J.R. Frost’s job- America’s finest citizens have waited tables and dug ditches…what I’m saying is that the Frost family were rye whiskey royalty and deserved better! The Frosts were taught to distill rye whiskey by a master distiller with distilling experience stretching back to the 1820s- at least, if not longer! (There had been Grays settled in Western Pennsylvania since the late 1700s!) It is a tragedy that such a wealth of distilling knowledge was allowed to fade into oblivion. I have reached out to descendants of the Frost family, and while no records seem to remain of their distilling past, we can still hold out hope that some piece of their legacy might resurface in time.