What happened within the distilling industry during the early years of Prohibition? In short, massive upheaval and a lot of confusion. The temperance groups that pushed for National Prohibition did not understand much about the liquor industry. Sure, they wanted to do away with the saloon and put an end to all the immoral inebriation, but they weren’t concerned with the complexities of the liquor industry itself. For all their bluster and cries to stop the evils of liquor, temperance fighters were not aware of (or prepared for) the fallout that would come from grinding a century-year-old industry to a halt. The Volstead Act explained how much jailtime offenders would receive and how big the fines would be if one was caught selling, manufacturing, or transporting liquor without a permit, but it did not explain what to do after hundreds of vertically integrated businesses collapsed. Distilleries supported a complex network of trade that included cooperage, bottling lines, gas and coal, packaging and shipping, grain commodities, stock trading, banking, advertising revenue, animal feed, water management, private sales forces, satellite business locations, and employment for entire populations of towns…oh, and the excise taxes collected from America’s distilleries accounted for approximately half of the Department of Internal Revenue’s yearly income. Without an intact distilling industry to manage itself, a whole lot of money was up for grabs and there were very few players in a position to scoop all that money up. Prohibition warriors fought hard to keep their countrymen from drinking too much, but in the end, their success only created a power vacuum which was quickly filled by corruption and illegal activity. The distilling trade which had been closely monitored by the government for so many decades was now out of its control. Many of those first few years of National Prohibition would be spent trying to make a bad idea work. New legislation would be passed every year or so to try to put Band-Aids on the gaping holes in the Volstead Act. Let’s look at those early years and how they set up what was to come.

In 1916 and 1917, America’s whiskey distilleries had been ramping up production as World War I threatened to cut off their grain supplies. They had been right to stock their warehouses with newly filled barrels because on August 10, 1917, the Lever Act, otherwise known as the Food and Fuel Act (or its longer name- “An Act to provide further for the national security and defense by encouraging the production, conserving the supply, and controlling the distribution of food products and fuel”) was passed by Congress. The nation’s distillers were all forced to shut down production to conserve grain supplies for the war effort. Their recent production push was going to hold them over for the next few years, but the temperance movement was bearing down on them as well. Even distillers that had been in denial about the movement for National Prohibition were beginning to realize that the end was near when Congress approved the “Resolution to enact National Prohibition” just a few months after the Lever Act was passed. Section 3 of that Congressional resolution provided a bit of optimism to those in denial, however. It stated that “This article shall be inoperative unless it shall have been ratified as an amendment to the Constitution by the legislatures of the several states, as provided in the Constitution, within seven years from the date of submission hereof to the states by the Congress.” There were many anti-prohibitionists that doubted the 18th amendment could be ratified within seven years and that the government would never be so stupid as to eliminate half of its income in excise taxes. But…as we now know all too well, they were wrong.

The 18th amendment was ratified on January 16, 1919 when Nebraska became the 36th state in the union to sign on with their approval. Ratification was achieved in only 13 months and would become law the following year. The Volstead Act was drawn up in 1919 to describe the terms and enforcement of National Prohibition. Once Prohibition became the law of the land, President Wilson appointed John F. Kramer, a lawyer and staunch prohibitionist from Ohio, to serve as the National Commissioner of Prohibition. Kramer was charged with managing America’s liquor and enforcing the Volstead Act beside the Secretary of the Treasury. He had just over 1500 agents at his disposal to police the entire country. Not only did Kramer not have enough men, but his officers were also poorly trained and underpaid. This bad combination quickly created a hostile environment for enforcement officers to interact with the people and businesses they policed. The enforcement arm of the Prohibition Bureau was looking good on paper but developing a bad reputation in the field.

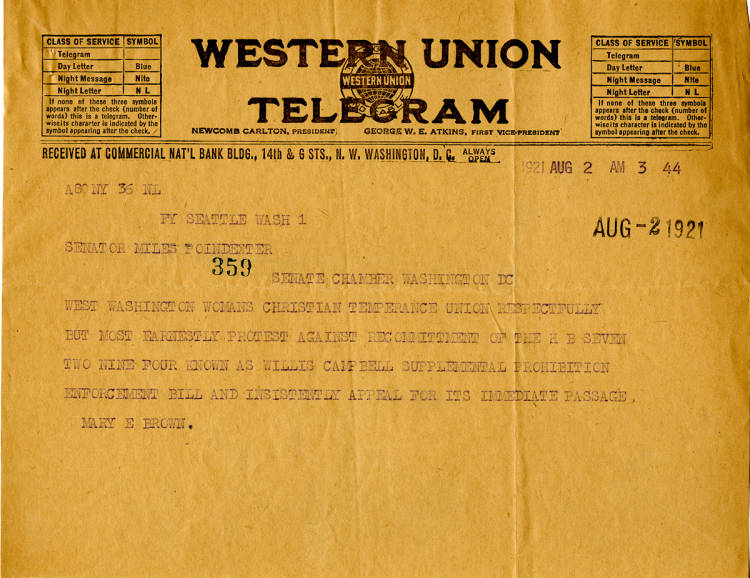

The Volstead Act gave the Commissioner of Prohibition the ability to supply permits to applicants that passed his scrutiny. Initially, permits to make medicinal whiskey were granted to a few distilleries known by the medical establishment to produce excellent quality medicinal whiskey. The Large Distillery in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania and the Gwynnbrook Distillery in Baltimore County, Maryland were two examples of companies that were able to secure permits and distill medicinal whiskey between 1919 to 1921 (2 distilling seasons). Many other companies, while not able to manufacture new whiskey, were able to apply for and secure permits allowing them to sell the contents of their government bonded warehouses through legal channels (i.e. to hospitals, pharmacies, medical treatment centers, etc.). The permit documents were pre-printed in books that the Commissioner or one of his appointees would sign and deliver to approved applicants. Unfortunately, some of these specially printed permit books were stolen or copied. (Not really too surprising, right?) The Department of Internal Revenue quickly found that transportation permits with forged signatures were being used to remove large amounts of liquor from numerous bonded warehouses across the country. When high ranking politicians or warehouse owners were indicted on charges of fraud involving these false permit documents, there were big public trials but very few convictions. The courts became so overrun with lower profile cases such as these that days were assigned where offenders were asked to show up to court, pay their fines and go.

While the courts were dealing with elevated criminal activity, it became obvious that the Volstead Act did not cover what to do with the tens of millions of gallons of liquor still sitting in America’s bonded warehouses. The new laws were forcing distillery owners into bankruptcy and leaving their bonded warehouses full of liquor unguarded. All that liquor in bond, by the way, was potential tax revenue for the government. Each time a large warehouse theft took place and criminals made off with dozens of barrels the Dept. of Internal Revenue lost thousands of dollars in taxes. There was no incentive for warehouse owners to invest in the protection of their barrel stocks because the Volstead Act cut them off from their own business and insisted that they continue to pay taxes on whiskey they had no means to sell or profit from. The rules of the liquor trade collapsed and were rewritten. Instead of doing business with a diverse customer base they had established over decades, distillery owners that were approved to sell medicinal liquor were only allowed to sell to medical establishments and pharmacies that had secured permits themselves. Most pharmacists had opted out of applying for a permit to sell alcohol because of the amount of hassle involved with adhering to the strict rules laid down by the Volstead Act. The market became so irregular with so few options for sales that only the largest companies with the greatest amount of whiskey stocks could navigate this new-fangled Prohibition-era liquor trade.

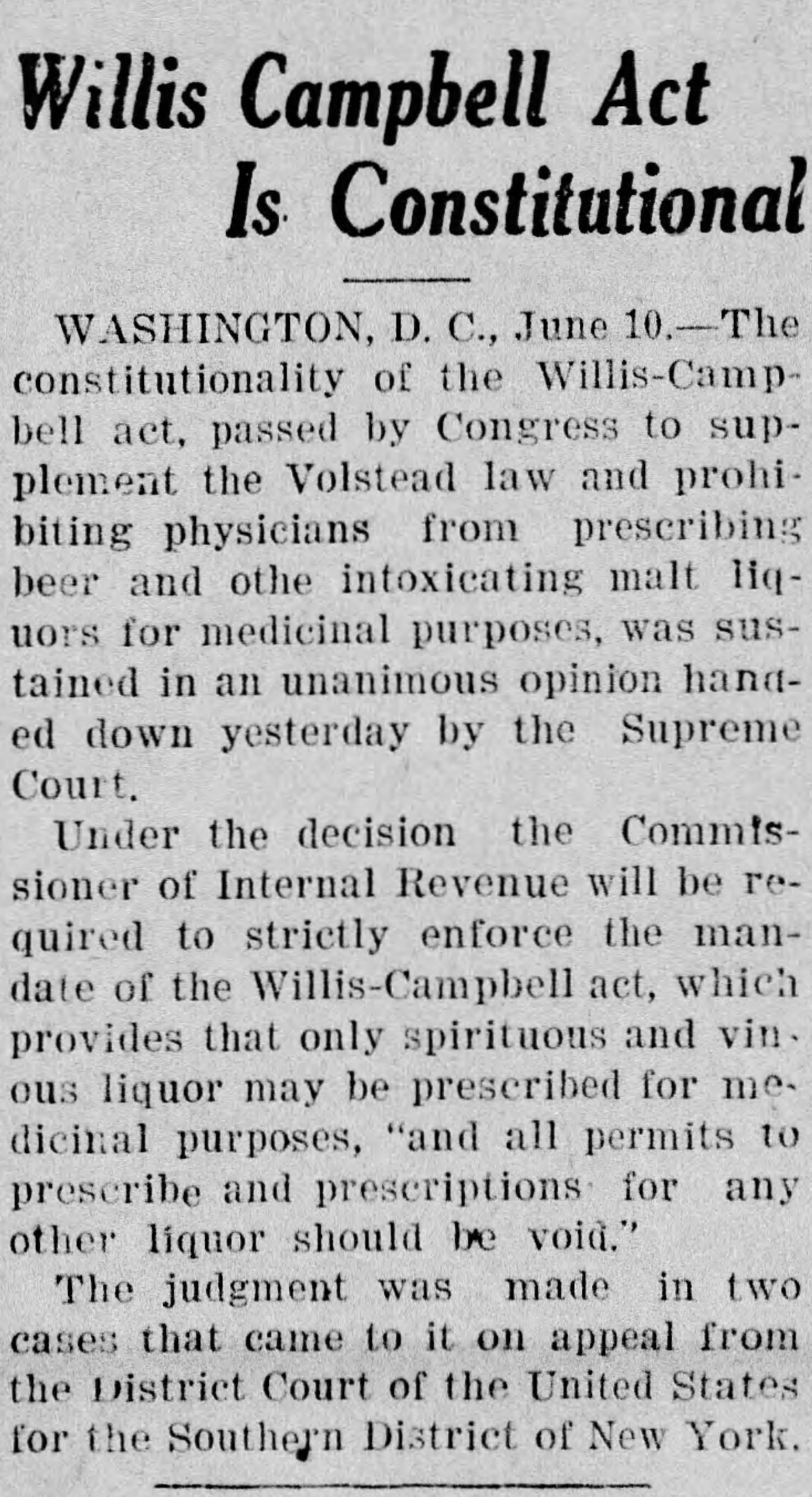

While the Volstead Act made allowances for alcohol to be used medicinally, it did not give specifics on what actually counted as medicinal alcohol. In 1921, the Willis-Campbell Act was passed to refine and tighten the restrictions imposed by the Volstead Act.

Initially, the Volstead Act stated that “Not more than a pint of spiritous liquor to be taken internally shall be prescribed for use by the same person within any period of ten days and no prescription shall be filled more than once.” The Willis-Campbell Act clarified this by saying that only “spirituous and vinous liquors” could be prescribed medicinally and reduced the maximum amount of alcohol per prescription to half a pint. This was the first time that beer had been excluded from the list of approved medicinal alcohol and beer makers immediately rose up in protest. (This is also why the Willis-Campbell Act is known as the “anti-beer law” or the “beer emergency bill.”) To slow down the amount of alcohol that doctors had been overprescribing that first year of Prohibition, the act also limited doctors to 100 prescriptions for alcohol per 90-day period. During Senate hearings in April 1926, testimony was given by Dr. William C. Woodward, a Chicago physician representing the American Medical Association, describing the clarifications made by the Willis-Campbell Act:

“It is all in the law except the interpretation as to the limit on the quantity of liquor that may be prescribed for internal and external use. The Volstead Act itself limits it to a pint of spiritous liquor that may be prescribed for any one patient in any 10 -day period. The Willis-Campbell Act limits the amount of vinous liquor to 1 quart in that period. There is a further prohibition that no spiritous and vinous liquors may be prescribed within any 10 -day period, the aggregate alcohol content of which is greater than 8 ounces or half a pint of alcohol. So you may say the limit is one-half pint of alcohol in 10 days.”

This helps explains why whiskey, even as the act describes allowing only half a pint every 10 days, remained a pint sized bottle. (An interesting note to be made here is that in 1916, the authors of The Pharmacopeia of the United States of America– a reference book of standards, identities, and formulas for drugs/medicines- took two liquors, brandy and whiskey, off the list of scientifically approved medicines. The American Medical Association also voted to advocate for prohibition in 1917.)

The medical community was divided on whether or not alcohol was, in fact, medicinal. There were vocal members of the AMA that argued for and against it. That argument became even more contentious as many doctors began making a great deal of money during Prohibition through the sale of prescriptions. Prescribing doctors made every effort, even with the contradictions coming from their peers, to point out that medicinal whiskey was a necessity. They certainly made a lot of money by charging those that could afford it $3 or more for every prescription.

When Warren Harding took over the office of President (after Woodrow Wilson) in 1921, he brought new appointees with him. Andrew Mellon became the new Secretary of the Treasury. Mellon, like Harding, had never been a “dry.” He repeatedly claimed to have severed all connections to his family’s legacy in the distilling trade, but the newspapers were never shy in pointing out that his friends all seemed to benefit from his position as Treasury Secretary. Harding also brought in Roy Haynes to serve as the new Commissioner of Prohibition. Roy Haynes, like Harding, was a newspaper man from Ohio. Temperance advocates praised Haynes for his tough crackdown on violators of the Volstead Act while anti-prohibitionists and distillers criticized what they felt was his abuse of office.

In the summer of 1922, the distillery/warehouse owners sent a series of resolutions to Congress and the President condemning Haynes and the activities of his “subordinate field officers.” They complained that their own legally sanctioned activities protected by the Volstead Act were being intercepted and undermined by the Commissioner’s men. These negotiations between distillery/warehouse owners and Harding’s administration helped form and solidify lobbying relationships that would be revisited many times over the next decade. Especially impactful were the relationships formed between Dr. Harvey W. Wiley (director of the Bureau of Pure Foods), Commissioner Haynes, and Edmund W. Taylor of Kentucky. Wiley and Taylor had formed a cozy relationship back in the early 1900s while the term “whiskey” was being defined (Read more about the Taft Decision HERE). Taylor advocated for “whiskey” to be defined as “only that which was aged in a barrel” while Wiley trumpeted Taylor’s opinion to Congress. In the winter of 1922, a decision was made that the only whiskey that could be legally sold to the public with a doctor’s prescription had to be “bottled-in-bond.”. It may have taken 15 years and a national ban on liquor production, but Wiley and Taylor were finally able to win their fight with rectifiers and make straight whiskey the only whiskey available to the public.

With warehouse theft and crime syndicates draining the nation’s supply of its bottled-in-bond medicinal whiskey, Congress also tacked on the following to the Willis-Campbell Act (Chapter 134, Section 2, 42 Stat. 222):

“No spirituous liquor shall be imported into the United States, nor shall any permit be granted authorizing the manufacture of any spirituous liquor, save alcohol, until the amount of such liquor now in distilleries or other bonded warehouses shall have been reduced to a quantity that in the opinion of the commissioner will, with liquor that may thereafter be manufactured and imported, be sufficient to supply the current need thereafter for all non-beverage uses…”

This clause in the Act effectively shut down any distilleries that had been distilling medicinal whiskey with permits (Large, Gwynnbrook, and any other distilleries with legal permits had produced about three quarters of a million gallons of new whiskey before the passage of the Willis-Campbell Act on Nov 23, 1921). Without imports, the country had to rely on whatever alcohol remained within its own borders. No distilling would be allowed again until the country had exhausted the contents of its bonded warehouses. Congress needed to protect whatever whiskey hadn’t been stolen or consumed during those first two years of Prohibition. They also needed to figure out the least expensive method of achieving this feat. They chose to consolidate the approximately 300 liquor warehouses around the country into just a couple dozen locations. This would vastly reduce the number of gaugers and government employees necessary to gauge and protect all those warehouses and put the nation’s liquor under a more manageable network of locations. Though the warehouse owners fought the Constitutionality of what was essentially government confiscation of private property, the Volstead Act placed the burden of proof of ownership on the defendant in any trial to recover seized liquor. The Supreme Court upheld the lower courts’ decisions allowing the removal of all privately owned barrels.

The Concentration Act of 1922 helped funnel approximately 30 million gallons of the country’s remaining whiskey into about 30 warehouses. The choices on who would take on the responsibility of housing all this whiskey were guided by special interests within the distilling industry. While nearly 80 applications were filed by American bonded warehouse owners to have their properties serve as concentration warehouse sites, about half of the locations chosen to house America’s liquor were in Kentucky. This decision was made after the Commissioner met with a handful of Kentucky representatives that assured him that they would absorb the costs associated with transportation, distribution, and protection of the barrels and would act as “stewards of America’s liquor.” (Remember those comfortable lobbying relationships?) This all took place as independent distillery and warehouse owners across the country challenged the constitutionality of the Concentration Act and fought to halt the government-sanctioned removal of their own warehouses’ contents. Their efforts were denied, and over the next few years, privately owned liquor was transported (under guard) into a couple dozen hand-picked warehouses that the government could more easily manage.

These concentration warehouses presented their own unforeseen issues. By 1924, as the youngest whiskey held in these warehouses was reaching 6 1/2 years of age (Some whiskey was reaching 11, 12, and even 13 years old!) and was quickly approaching what had been known within the distilling industry as the mandatory “7 year re-gauge.” For context- In 1894, the “Carlisle Law” extended the bonding period for aging whiskey from 4 to 8 years with a scheduled regauge of every barrel at 7-years-old to assess its losses (a maximum allowance of 13.5 gallons of loss were deducted before taxes were assessed on each 48-50 gallon barrel). “The Carlisle Law” had only been enacted to save the Kentucky bourbon market from collapse in the mid-1890s. Overproduction would have bankrupted Kentucky’s bourbon makers if they had not been granted an extension delaying the taxes due on their aging barrels. Once the bourbon industry recovered, whiskey seldom reached 8 years old and was usually removed from bond before 6 years old! While the 7-year regauge had never really been an issue before Prohibition, it had certainly become one now. Before 1920, distillery warehouse owners kept meticulous records of the contents of their bonded warehouses and of the receipts they held for owners (banks, rectifying houses, private citizens, etc.). It was their business, after all, and they had a personal stake in the management and organization of their whiskey stocks. Once the liquor from hundreds of distilleries began being consolidated in the early 1920s, it became more difficult to manage the contents of concentration warehouses. Not only were the warehouse owners not sure how to handle this 7-year regauge of barrels- after all, they had come from warehouse locations all over the country-, they hardly knew who owned what or who to send the bill to for excise tax payments.

Warehouse owners found it difficult to determine the ownership of the whiskey that was reaching the end of its bonding period. They didn’t know who to bill for the government excise taxes that were coming due. Why was this even an issue, you ask? Because the Volstead Act made it clear that all Internal Revenue excise laws established before Prohibition still applied. This meant that every barrel of whiskey in a concentration warehouse nearing 7 years of age would need to be re-gauged. Otherwise, the tax on the liquor when removed from bond would be assessed on the barrel’s original fill level. Usually a barrel lost about 12-15% of its contents after 7 years through soakage and evaporation, so the cost to the warehouse owner and the losses in government tax revenue would be significant. The warehouse owners petitioned Congress and asked that the 7-year regauge be eliminated and the barrels within the concentration warehouses be left alone to age uninterrupted. They assured Congress that hundreds of thousands in government tax dollars would be saved if the barrels were only taxed when they were removed. Unsurprisingly, Congress agreed. The whiskey could stay put and grow older as Prohibition dragged on…

We’ll look at what those warehousemen get up to after 1925 in the next entry. Hint: It’s to their benefit. Go figure.