On November 23, 2024, at George Washington’s Mount Vernon Distillery in Alexandria, Virginia, an incredible lineup of historic bottlings of rye whiskeys were sampled. The focus was on antique expressions of Mount Vernon rye whiskey. specifically. For me, the tasting was an opportunity to trace the history of several famous distilleries and the trajectory their whiskeys followed with each passing year. The following notes are NOT tasting notes. They are notes on the history of the bottles and how the whiskey reflects upon that history.

Before we get into the individual bottles and their contents, there’s an important point to make clear. If you’ve ever wondered why Mount Vernon was such a popular brand of rye whiskey, why it’s been bottled/labeled in so many different ways over the years, or why there are so many differing opinions on which of its iterations are the most desirable…There are very good reasons for all these differences! The most important piece of this historic whiskey brand’s puzzle is the fact that the Hannis Distillery in Baltimore Maryland was THE ONLY major manufacturer of pure rye whiskey that was purchased by the Whiskey Trust in 1899. Being the only rye whiskey distillery owned by the Trust placed Mount Vernon rye whiskey front and center within the whiskey trade. It had become the sweetheart of the largest, most aggressive whiskey company in the country at the turn of the 20th century.

1899 was a pivotal year for the American whiskey industry because the Whiskey Trust, under its new corporate identity, the American Spirits Manufacturing Company (ASMC), was reorganizing itself and finding new, legal avenues of approach to achieving their goals. Their goal was to consolidate and manage as many different aspects of the trade as possible through its subsidiary companies. Where the Distiller and Cattle Feeders Company had failed in Peoria, its new corporate identity with its new offices in New York City, would succeed. The ASMC, which was incorporated in 1895 immediately after the Distiller and Cattle Feeders Company (Whiskey Trust) was officially dissolved, was composed of the following subsidiaries by 1899:

1. The Spirits Distributing Company- formed in 1896 to manage product distribution

2. The Standard Distilling and Distributing Company- formed in 1896 to manage the purchase of distilleries and distributing plants

3. The American Spirits and Refining Company- formed in 1899 to manage industrial alcohol production

4. The Kentucky Warehouse and Distilleries Company- formed in 1899 to manage the large number of Kentucky distillery properties and warehouses that had been acquired by the Standard Distilling and Spirits Co. since 1897.

The Whiskey Trust negotiated options to buy out Pennsylvania and Maryland’s rye distilleries in the same manner they had purchased Kentucky’s distilleries. The Times in Philadelphia described negotiations: “It is of the utmost importance to the success of the syndicate that it obtain control of the trade in Pennsylvania and Maryland, which is the most profitable. Heretofore the whiskey distilling interests in these two states have been entirely free from combinations and their superiority in the field has been unquestioned.” In early July 1899, the Trust was able to purchase the Hannis Distilling Company in Baltimore (Mount Vernon Pure Rye Whiskey among other brands) for $1-2 million. The company had suffered many setbacks over the years- including the death of Henry Hannis*, and the Trust was able to take advantage of its weak position. The same month of the sale, a new, larger corporation called the Distilling Company of America was formed as an umbrella company to serve all of the trust’s new (and assumed) assets. The plan was to add at least 14 rye whiskey distilleries to their portfolio and create another subsidiary representing those properties which would mirror what they’d done with the Kentucky Warehouse and Distilleries Co. A huge, unexpected problem arose, however, when they failed to secure any of the other large rye whiskey manufacturers. Their inability to acquire America’s rye whiskey manufacturers forced the Whiskey Trust to admit that their plans to create a company controlling the interests of America’s whiskey producers had failed. By 1902, the Distilling Company of America was licking its wounds, apologizing to its stockholders for devaluing their assets, and amending its charter by lowering its authorized capital stock from $125,000,000 to $85,000,000.

The reason that all this information is critical to understanding the whiskeys in this tasting is that Mount Vernon rye whiskey became the sweetheart of the new Whiskey Trust! Part of the reason that rye whiskey distillers were able to deny the trust is because their financial position was secure at the turn of the century! Rye was very popular with consumers and held its value in the market even as overproduction had become an issue for most US distillers. Mount Vernon became the go-to rye whiskey brand for the American Spirits Manufacturing Co. (aka the American Medicinal Spirits Co. after 1927) during and after Prohibition and was advertised heavily as the greatest rye whiskey being sold at the time. While Prohibition opened a floodgate of new brand options for the Trust, those stocks of Hannis Distillery’s rye whiskey were always at their disposal. As the American Spirits Manufacturing Company evolved and course corrected with the advent of Prohibition, Mount Vernon rye whiskey went along for the ride! The brand was constantly changing hands and reinventing itself. These bottles are small time capsules that reveal the idiosyncrasies of the American rye whiskey market over time.

Whiskey No. 1- Mount Vernon Rye. Bottled by Macy & Jenkins. Distilled in 1902. No bottled-by date.

This whiskey was manufactured at the Hannis Distillery and shipped to New York City in barrels where it was bottled by the highly reputable liquor firm of Macy & Jenkins for Edwin G. Bruns. Bruns was a very wealthy socialite/businessman in New York and preferred well-aged ryes, so the assumption is that this bottle was an older rye whiskey. A 90-proof rye, it followed the characteristics of a Monongahela-style Pennsylvania rye- citrus and stone fruit, very dense mouth feel, lots of vanilla cola notes. The ultimate goal of Henry Hannis at his distilleries was to create a Monongahela-style rye for his Philadelphia based firm, but Hannis was obviously not alive by 1902 when this was distilled. The distillery, by 1902, was under the ownership of the Trust, but the assumption can be made that the distillery was operating as it had been before the sale. This was real pre-Pro Hannis Distillery whiskey and it was lovely. To be clear, it is impossible to know if this whiskey was altered in any way. The assumption is that this was a pure rye from a single barrel. Macy & Jenkins was a highly respected firm, but we can not apply modern ideals onto a whiskey that was bottled before Prohibition. Legal standards for identity did not exist until 1935. What we CAN assume is that Macy & Jenkins would not have jeopardized their reputation for fine spirits. Even a slightly “adulterated” whiskey would have been expertly blended to suit their customer’s tastes.

As a side note, there were TWO bottles of this Mount Vernon rye whiskey (bottled for Edwin Bruns) available to sample at the tasting. The bottle poured for the group was slightly cloudy, while the other was quite clear and slightly darker in color. The clear whiskey seemed to have lost less of its potency over time, though its flavor profile was very similar. In my opinion, these whiskeys were the same spirit when bottled, but had experienced a slightly different life on the shelf.

Whiskey No. 2- Mount Vernon Pure Rye Whiskey. Bottled by Cook and Bernheimer. Distilled Fall 1913. Bottling date unclear.

We return to to the ideal scenario of this whiskey being distilled at the Hannis Distillery in Baltimore, Maryland. Cook & Bernheimer was a New York liquor firm that was granted exclusivity for the bottling and distribution of Mount Vernon rye for Hannis Distillery in 1889, but we can see the conundrum presented by the fact that Macy & Jenkins obviously bottled their whiskey, as well. It may be that Macy & Jenkins owned barrels of Hannis’ whiskey that they had kept in their own private warehouses, but it’s more likely that Cook & Bernheimer’s exclusivity had more to do with the shape of the bottle than with the whiskey itself. (I found other examples of companies that bottled rye whiskey manufactured at the Hannis Distilleries, but not Mount Vernon rye whiskey.) The Hannis Distillery had bottling houses on site at both their Baltimore and West Virginia locations by the late 1800s, though Cook & Bernheimer specified that their square bottles of Hannis’ Mount Vernon was bottled at the original Hannis Distillery in Baltimore, Maryland. There’s no reason to believe that the whiskey bottled by Cook & Bernheimer as bottled-in-bond straight rye whiskey had been altered in any way.

Mount Vernon rye whiskey’s “square bottle” had been used by the distillery before it became synonymous with Cook & Bernheimer, but the firm valued that bottle shape and its recognition within the whiskey trade. This bottle of rye whiskey was quite different than the Macy & Jenkins Mount Vernon rye, and we know that Cook & Bernheimer bottled “at the distillery”, so while they were bottling the same product from the same distillery, they handled the whiskey differently. Whiskey No. 2, bottled in 1913 by Cook & Bernheimer, was manufactured 11 years after the Macy & Jenkins bottle, but was still the product of the Hannis Distillery. A modern example we might use to illustrate the difference between these bottlings might be to look at rye whiskeys manufactured by MGP today. The same whiskey, bottled by two separate companies might be quite different from one another. The bottle of Mount Vernon rye by Cook & Bernheimer seemed to be the highlight of the evening for most attendees of the tasting. I found it to be very fruit forward with a creamy, candy sweetness. The minerality on the finish hinted at the possibility that the whiskey had been altered in some way, but likely had more to do with oxidation over time. With old whiskeys, it’s very hard to say with certainty. It was an incredible pour, nonetheless.

Whiskey No. 3. Hannis Distilling Company. Bottled in Bond. Distillery No. 1, Martinsburg, West Virginia. Distilled 1913. Bottling date unclear.

Henry Hannis built his distillery in Baltimore in 1863, but his demand outstripped his supply rather quickly. He expanded his production by purchasing a second plant in Martinsburg, West Virginia just five years later. By 1868, Hannis was running two facilities in two different states to satisfy demand. I was particularly interested in this sample of rye whiskey because I had never tasted anything that was manufactured at Hannis’ second location. Obviously, it is difficult to trace the potential of any distillery’s products over the course of 40 years through one bottle, but the opportunity to taste a small sample of that long history, even through a small sample from the end of that timeline, was an incredible experience. Surely, if there’s anything that a modern whiskey enthusiast can appreciate, it’s the difference that a few decades can make upon the quality of a distillery’s products! This bottled-in-bond rye was made in 1913 in a distillery that was likely of secondary importance to its owners. It certainly had a pre-Pro character, but the whiskey, perhaps unsurprisingly, fell fall short of expectations. When I inquired what the flaw in the spirit might have been, a talented distiller standing next to me described its flaw as “geosmin.” Geosmin is a chemical compound produced by soil bacteria and blue-green algae and is often noted in the flavor of mushrooms. The distiller noted that it may have been due to rushed or sloppy fermentation practices. As curious as this may seem at first, it made a lot of sense! In November 1912, 69.4% of West Virginia voters approved an amendment to the state constitution that would prohibit alcohol production in their state. West Virginia’s state-wide Prohibition had become inevitable when this whiskey was being manufactured! The “Yost Law” in West Virginia (its own state Prohibition law) became effective on July 1, 1914. This whiskey sample, which had been manufactured at Hannis’ Martinsburg Distillery in 1913 was made in haste! It possessed some of the qualities that one might expect from Hannis’ Baltimore whiskeys, but it fell so far short of the previous samples (understanding that it had been made in West Virginia, not Baltimore) that one could not wonder why it was so…less. It seems the history answered that question for us.

Whiskeys No. 4 & 5- This was a comparison tasting of two bottles, both manufactured at the Gwynnbrook Distillery in 1921.

The first was a quart sized bottle labeled “Mount Vernon Straight Rye Whiskey” – Bottled-in-Bond by National Distillers in 1933. Distilled by Gwynnbrook Co. Gwynnbrook, MD. The second was a medicinal, pint sized bottle- Bottled-in-bond by the American Medicinal Spirits Co. of Baltimore, MD in 1931.

The most important thing to make clear about these two whiskeys is that while they are labeled as Mount Vernon rye whiskeys, they were NOT manufactured by the Hannis Distillery in Baltimore. These rye whiskeys were made in 1921 by the Gwynnbrook Distillery, located just outside of Owings Mills, Maryland. Gwynnbrook was one of two rye whiskey distilleries that were legally manufacturing medicinal whiskey between 1919 and 1922. The other was the Large Distillery in Large, Pennsylvania. Neither of these rye whiskey distilleries have been credited with producing whiskey during Prohibition by modern whiskey historians, but that is most likely due to the lack of historic research focused specifically on rye or other “non-bourbon” American whiskeys. Both bottles were almost certainly manufactured at the Gwynnbrook Distillery, but the tasting revealed how the nature of the whiskey in their bottles diverged from one another.

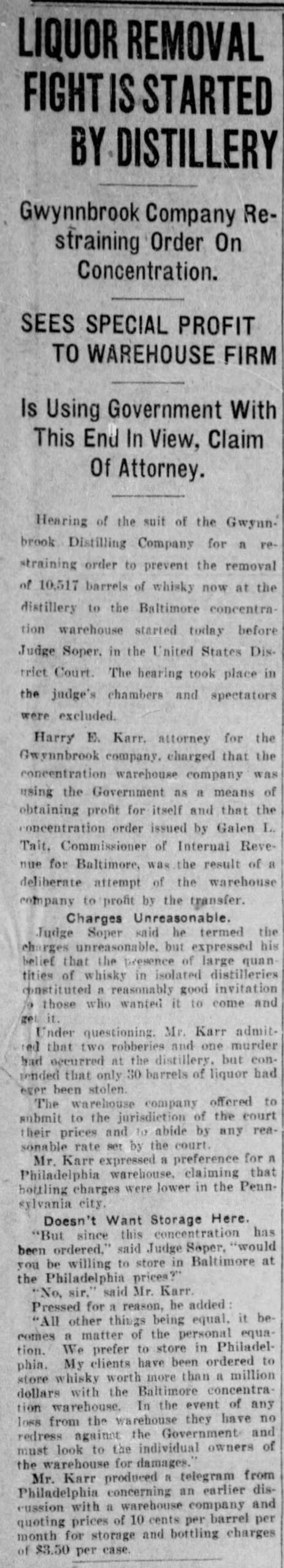

The pint-sized medicinal bottle of Mount Vernon rye whiskey that was “bottled in 1931” may have been bootlegged and/or adulterated whiskey. This speculation is based on the fact that a large amount of whiskey that had been stored in Gwynnbrook’s warehouses was stolen after Prohibition went into effect. (There were several articles describing theft from the Gwynnbrook Distillery’s warehouses during Prohibition, but the most notable heist was in 1923.) In 1922, the US Treasury Department began to enforce the Concentration Act- legislation which ordered the consolidation of America’s whiskey into about 26-30 government-controlled warehouses. The remaining contents at Gwynnbrook Distillery (about one million dollars worth of whiskey stocks) were ordered to be moved to US bonded warehouse No. 27 in Baltimore, which was controlled by the Trust (ASMC). The owners of the Gwynnbrook Distillery’s warehouse fought the order in court, preferring to move their whiskey (and the whiskey being stored on site for private citizens) to the bonded warehouse in Philadelphia.

Their lawsuit was unsuccessful, and the entirety of the warehouse’s contents were moved under heavy guard to Baltimore in 1924. Gwynnbrook was not unique in its losses due to theft. Most whiskey warehouses were being plundered after 1920! The Mount Vernon rye whiskey pint, bottled in 1931, was bottled DURING Prohibition, so there is no way to prove one way or another that it was done without government oversight. Tax stamps were often stolen and forged during Prohibition, and whiskey was often altered before it was sold to the public. We’d like to think that a tax stamp over the cork of a bottle is a sure-fire way to prove authenticity, but that is NOT always the case. The consensus in the room at the tasting was that the sample of Mount Vernon/Gwynnbrook rye whiskey bottled in 1931 was very flawed. It lacked the full-bodied character of a pre-Pro rye whiskey and tasted as if it had been cut with neutral grain spirits. While arguments among those present at the tasting proposed theories that the bottle’s contents were damaged during production, I proposed that the whiskey may have been adulterated by bootleggers looking to stretch stolen merchandise. There is no way to prove either theory without scientific analyzation of the bottle’s contents, but either way, the sample pour was flawed. The whiskey poured from the second quart-sized bottle of Mount Vernon, also distilled at Gwynnbrook in 1921, presented a stark contrast to the pint.

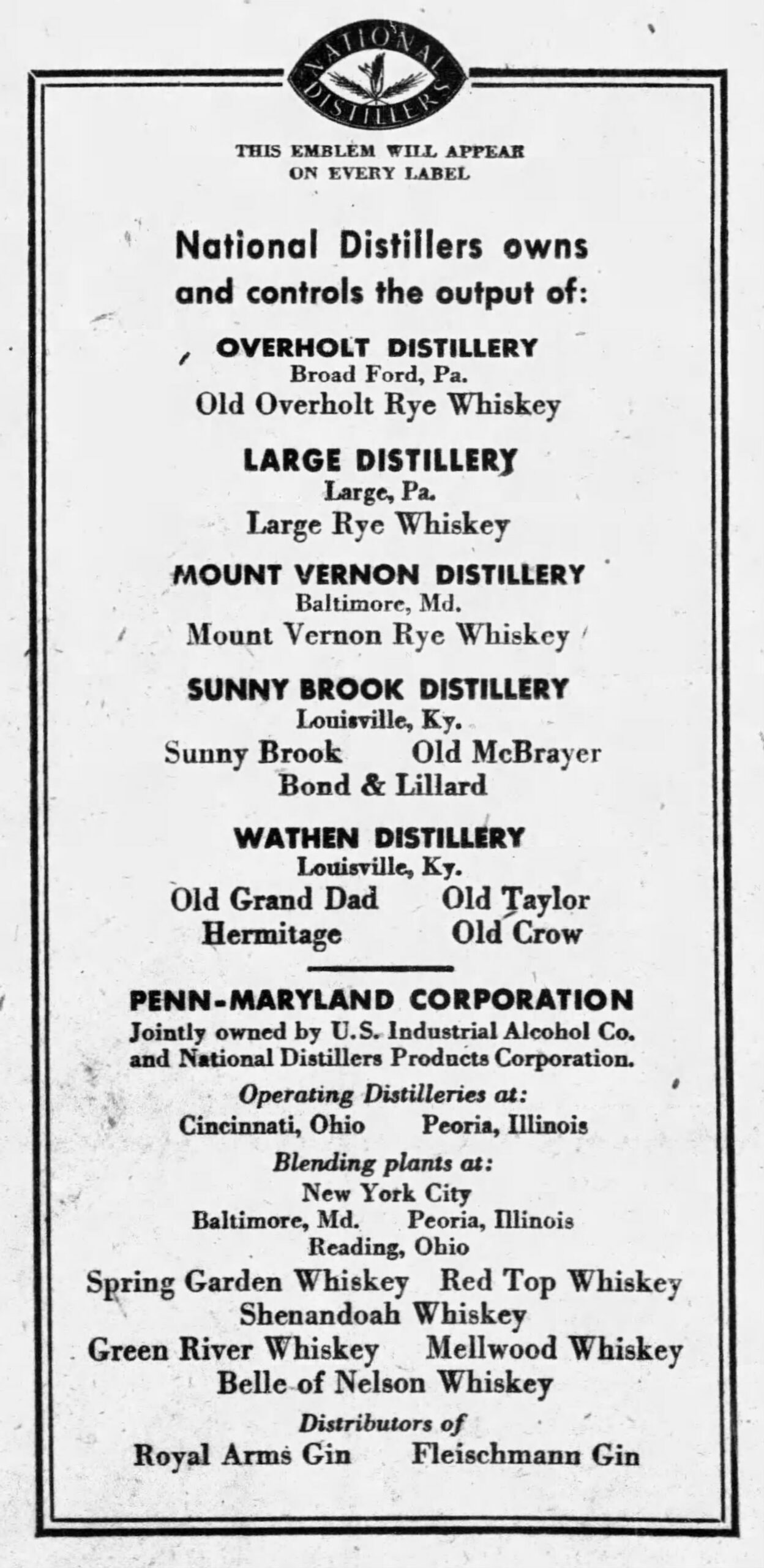

The quart sized bottle of Mount Vernon’s Gwynnbrook rye whiskey from 1933, however, was far superior. It tasted of coffee ice cream and had a much more complex flavor profile, overall. Both whiskeys were bottled by the same company under different aliases, but the fact that the Mount Vernon/Gwynnbrook rye bottled by National Distillers was superior speaks more to the time in which it was bottled than anything else. National Distillers was the new corporate face of the American Medicinal Spirits Company in 1933, and there was a new push to sell high quality spirits at a higher price point once Repeal went into effect. The remaining whiskey that had been manufactured in 1921 by Gwynnbrook Distillery were still intact in the warehouses owned by the Trust, but those barrels were now 12 years old! The value of pre-Prohibition medicinal whiskey to consumers soared once it became legal again, and National Distillers was not going to squander the opportunity to sell high-quality products to a high-priced market with buyers that knew the difference. The market then was not so different than the market is today- old whiskey was sold at much higher price points to sell to consumers that were willing to pay for the real thing. If there is an excuse to be made for why the fifth of Mount Vernon was superior to the pint version bottled two years earlier, this is my explanation. Whether it is true or not is entirely conjecture- but possible considering the historic context.

As an aside, I wanted to make it clear that any whiskeys bottled by National Distillers naming the distiller as “Gwynnbrook Distilling Co” AFTER 1921 were NOT distilled at Gwynnbrook Distillery. While National Distillers owned the name “Gwynnbrook Distilling Co”, they did not own the distillery property or its warehouses. I have seen bottles labeled “distilled in 1931” that were credited as being distilled at Gwynnbrook, but that is a case of National Distillers being disingenuous. There are many bottlers that use these same tactics today- labeling their whiskeys with names of distilleries that do not physically exist. These are often called Non-Distiller Producers, or NDPs.

In October 1929, The AMSC incorporated 17 distillery companies to be based in Louisville. This did not mean they meant to reopen any distillery facilities. What it meant was that they would use the company names on labels of bottles filled from barrels within their concentration warehouses. (The practice of incorporating defunct distillery names “for bottling purposes only” is often done today, but this was the first time it was done on this scale in the past.)

The American Medicinal Spirits Company’s newly incorporated names were: The Green River Distillery Company, The Hermitage Distillery Company, The Gwynnbrook Distillery Company, The Chicken Cock Distillery Company, The Bond and Lilliard Company, The Black Gold Distilling Company, The Medical Arts Distillery Company, The Mount Vernon Distillery Company, The Old Crow Distillery Company, The Old Grand Dad Distillery Company, The Old McBrayer Distillery Company, The Old Taylor Distillery, The Pebbleford Distillery Company, The Spring Garden Distillery Company, The Federal Distillery Company, The Sunnybrook Products Company.

Whiskey No. 6- Mount Vernon Brand Straight Rye Whiskey. Bottled-in-Bond by National Distillers Products Co. (square bottle) Distilled by the Hannis Distilling Company in Spring 1935. Bottled Spring 1941.

Here, we move into the post-Prohibition era. National Distillers, the new face of the old Whiskey Trust, was the largest owner of whiskey stocks in the country. Their rye whiskey distillery in Baltimore, Maryland had been renamed the Mount Vernon Distilling Company in 1933.

The curious thing about this bottle is that most of the whiskey that was being labeled as “Mount Vernon Brand Straight Rye Whiskey” in 1941 by National Distillers was being labeled as “distilled by Mount Vernon Distilling Company.” They were NOT being labeled as “Distilled by Hannis Distilling Company” because that company no longer existed, except on paper! National Distillers owned the name “Hannis Distilling Company”, but the old Hannis Distillery had been known as the Mount Vernon Distillery since before the whiskey in the bottle was distilled! Why label it “Hannis Distilling Company”? Another curious fact is that a charter was filed in Delaware for the incorporation of a “Hannis Distilling Corporation” in July 1941. Its offices were in Wilmington, Delaware. Several similar bottles like this one have been auctioned off over the years (yellow caps labeled “Distilled by Hannis Distillery Company” from 1941 and ’42), but it’s unclear what the contents of these bottles might have been! The whiskey inside was definitely flawed. The distillers in the room seemed to think that the mash had been infected during fermentation. While the whiskey had a strong spoiled fruit funk to it, there was also a distinct note of urea. This note was almost certainly the result of a bad batch made in the distillery. It was not the kind of note that would come from cork taint or oxidation. Was this bottle distilled at Mount Vernon Distillery in Baltimore, or was it distilled by another distillery belonging to National Distillers? Is it the result of National Distillers rushing some whiskey to market? Was it bottled under the Hannis name to separate it from the rest of their products? Without further research, it’s very hard to say!

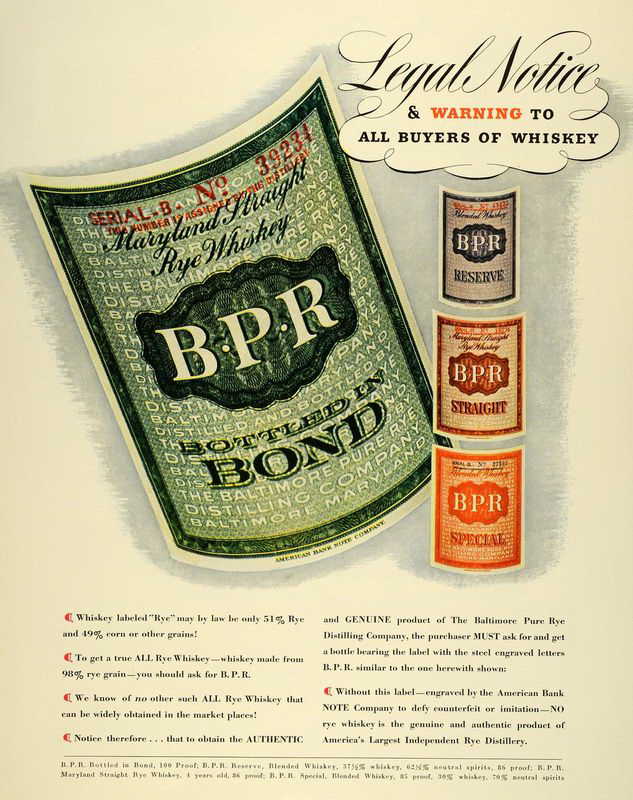

Whiskey No. 7- BPR Maryland Straight Rye Whiskey. Bottled-in-Bond by Baltimore Pure Rye Distilling Co. Distilled Fall 1937. Bottled Fall 1941.

This whiskey, other than being a Maryland rye whiskey bottled in 1941, has nothing whatsoever do to with the previous whiskeys, Hannis, or Mount Vernon. This was distilled at the Baltimore Pure Rye Whiskey Distillery in Dundalk, Maryland. The master distiller at this distillery returned to distilling rye whiskey after the long dry spell of Prohibition. His name was William E. Kricker. I’ve written about him several times in the past to rave about his contributions to the history of Maryland rye whiskey. The ad below is from 1941- the same bottle we were tasting. “The most famous whiskey state’s most famous whiskey.” Imagine that?! A state famous for whiskey that isn’t Kentucky! How times have changed:)

This whiskey was viscous and rich with cherry syrup, stone fruit, and peach cobbler. It had a rich, almost dessert-like quality. This was my favorite pour of the evening- though it was a close one…with the following pour.

Whiskey No. 7- BPR Maryland Straight Rye Whiskey. Bottled in Bond by the Baltimore Pure Rye Distilling Co. Distilled Spring 1940. Bottled Spring 1947.

Though most of America’s rye whiskeys had become history after Prohibition, BPR stood against all odds, manufacturing a pre-Pro style Maryland rye that Americans could be proud of. It was made with a three chamber still using a 98% rye mashbill. When asked about the rye he used, Kricker was not entirely specific, but explained,

“We like here a well-balanced grain with the right proportions of protein and starch content. Light bodies whiskeys require a 12 to 14 per cent. protein and a 50 to 54 per cent. starch sugar. For a heavier bodied product, you will want more protein and less starch.”

This was an elegant rye. Really a quintessential representation of a post-Prohibition, bottled-in-bond Maryland rye whiskey. Delicious.

*While Henry Hannis is a legend in the American whiskey trade, the latter part of his life was awash in tragedy- and not just because his distillery was the lone rye whiskey distillery to became part of the Whiskey Trust’s empire about a decade after his death. Henry was committed to the Pennsylvania State Insane Asylum at Norristown in the early 1880s. His life would end in that asylum. One of the Hannis Distillery’s storekeepers at Martinsburg, Va committed suicide with a pistol in 1897. Hannis’ son, Herbert E. Hannis, would end his own life by overdosing on laudanum in 1906.