One of the most amazing steps in making whiskey is the one of the first steps and is often overlooked in its importance.

The first step is farming the grain, of course. This is incredibly important in determining the quality of the grain. So much is dependent upon the growing season, weather, rainfall and soil quality. One harvest will differ from the next. After the harvest, it’s the maltsters turn…

Many grains are used in making whiskey, especially now that so much experimentation is being done to create craft whiskeys. They can all be malted, but no grain has the diastatic power (enzyme power to convert starches to sugars) that barley has. It is called the “workhorse grain” because it is often added to a mash in small amounts just for its wonderful enzymatic properties. You’ll see grain mashbills with 95% rye and 5% barley, for instance. The barley is added for its enzymes, not necessarily for its flavor contribution.

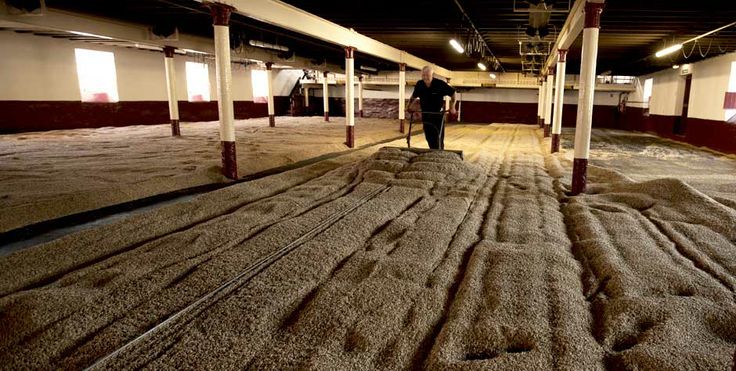

The techniques employed in malting barley may differ slightly from malthouse to malthouse, but they must follow the same basic steps. First, the grain must be steeped. Steeping is the process of soaking the grain, often in a large cistern. This is done to encourage the grain to wake up, activating its enzymes, in its normal attempt to become a plant. (this may take 40-60 hrs) Next, the grain is couched, allowing the temperature of the grain to rise, the husk to slightly dry and germination to begin. Third, the grain is spread onto a malting floor (about a foot deep) where the temperature will continue to rise and the even germination of the seeds can be controlled. The barley seed’s germination is closely monitored keeping its temperature below 60 degrees by turning it over with shovels and altering the temperature of the room. The little rootlets will form, but the acrospires (the part that will become the plant) is not allowed to sprout. The floor malting is very important in allowing the full flavor potential of the seed to develop (This process can last up to 12 days). Just when the seed is about to sprout, the process is halted by kiln drying. The “green malt” (as it is called after flooring) is laid out over a heated floor or mesh which allows heated air to pass through the grains and dry them out. In peated whiskeys, smoke passes through the seeds as well, imparting them with a smokey flavor that passes into the whiskey.

Malting is an art in itself. A skilled maltster can affect the flavor that the grain has to offer in their handling of the grain. Their experience and knowledge of the individual grains and how they respond during the process affect the quality of the malt. It can often be taken for granted that the distiller is the reason that their whiskey tastes so good. But just as a chef can only create meals as delicious as their ingredients, a distiller can only make whiskey as good as his grains. Malthouses and their maltsters are the under-appreciated superstars behind our favorite whiskeys.