After the last blog post, I was reminded by a fellow enthusiast that I should have included that “rye whiskey is hard to make”. It gave me pause so I figured I better address it.

I did not include that rye grain mashes can be difficult to work with because I do not believe that it was a contributing factor behind rye whiskey not surviving Prohibition. The first reason among the 8 I provided was that rye was expensive, both to grow and to purchase, but I did not make mention of how difficult it may be to work with in the distillery. After all, these difficulties are not likely something that an experienced distiller in the early 20th century would have been affected by. Not to put too fine a point on it, but if you are an experienced Formula One racecar driver, you probably aren’t overheard complaining about how hard it is to drive stick. I did not include the various diseases that can infect the plant or explain the issues involved with storage, cleaning etc. because these things relate to the level of skill and experience of the rye grower/farmer, not with the value of the seed. I suppose the same thing goes for a distiller. The frustrations that may arise while learning to distill rye whiskey have less to do with the unique charactreistics of cereal rye creating a thick, sticky, slimy mash and more to do with the skill and experience of the distiller. Do NOT get me wrong! I LOVE distillers. I love their rye whiskey. I am not disparaging the incredible skills that exist in the distilling world- especially because I am not a distiller myself and harbor no illusions around ignorance! In fact, the rye whiskey-making experts that come from the old Seagrams plants like Larry Ebersold, Jim Rutledge, and Greg Metze are some of the most knowledagble rye whiskey makers alive (not to mention are heroes of mine). That being said, their expertise is based upon a post-WWII distilling tradition. As highly respected and quality-controlled as that style of whiskey making is, it is unpreventably different from the old Pennsylvania and Maryland way of doing things. Most up-and-coming modern distillers become familiar with mashing corn or sugar in their early years. Even their equipment is designed for the manufacture of sugar shine, rum, gin, vodka, corn whiskey or bourbon. In fact, most of what modern distillers are taught is centered around these mashes and the techniques involved with their fermentation and distillation. What modern distillers do not know about the manufacturing of traditional rye whiskey styles is not their fault. This is where reason #6 for rye whiskey’s disappearance comes in: The loss of generational expertise in making rye whiskey was devastating. We are, in a sense, “redesigning the wheel.” It took about 150-200 years to craft the meticulous process employed in distilling rye whiskey, but it only 13 years to disrupt the entire industry.

I pulled this from a WhiskeyWash article:

“The Impact Of Small Rye Grain“ by Fred Blans. January 17, 2020

Distilling a rye mash bill is a tedious job. ‘Those beta glucans are the problem of distilling rye. The proteins thicken the mash and give it a slimy consistency. These properties make it more difficult to mash in rye. We cannot mash in as much grain per 10,000 liter mash as we would if we distill from corn or wheat. That means a less high gravity for the distiller’s beer and more energy and water used per liter of whisky. So a higher cost per liter and less yield per distillation’.

The truth is that modern distillers find rye whiskey difficult to produce because there are no “How to” books written by 19th or early 20th century rye whiskey distillers for the new guys to read. The masters instructed their apprentices and the expertise remained within the insular rye whiskey distilling community. They didn’t write down production tricks-of-the-trade, and even if they did, that information was kept private. It was likely not proprietary per se, it was just that these methods were well understood within the rye whiskey distilling community. They knew how to work a rye mash under differing weather conditions, how to maximize starch conversion, and maintain their mash without it getting clumpy or too viscous. Between the Civil War and Prohibition, rye distillers brought their output from 2 gallons of whiskey per bushel of rye to a up to 4.5 gallons per bushel. Today, 4.5 may seem like a low yield, but, again, we’re not talking about corn or sugar and ALL of this was done without the aid of enzymes. How did they manage to craft such highly sought after whiskeys without modern machinery or enzymes? Well, to start, they had about 150 years to perfect their product and plenty of experts to bounce ideas off of.

We tend to forget that most distilleries before Prohibition were smaller in scope, and they had dozens of other locally competitive distilleries nearby. Newspaper articles throughout the late 1800s record stories of young men right out of school training with experienced distillers as apprentices. They would work in one or several different locations before either settling in as head distiller for a distillery or striking out on their own. Often they were sons of distillers, but were just as often sons of millers, coopers, lumbermen, coal mine owners or farmers. These businesses all interacted with one another, so the distilling trade was not isolated from these skillsets in the way that they are today. Another popular line of work that led men into distillery ownership, believe it or not, was politics. A young man with good connections could secure a politically appointed position as a gauger for the Department of Internal Revenue. It was a very well-paying job that gave a man a very intimate knowledge of the industry. After a few years as a gauger learning the idiosyncrasies of the trade, many purchased their own distilleries or went in as a partner in a liquor firm. Though usually not distillers themselves, the increasing number of ex-gauger distillery owners over the years certainly affected the industry’s internal politics. One of the more famous ex-gaugers to have a big impact on the American whiskey industry was William Howard Taft, author of the “Taft Decision.” Understanding the inner workings of the distillery and understanding the complex art of distillation, however, were two different things. Businessmen that bought distilleries knew that the secrets and generational knowledge possessed by highly experienced distillers was priceless and sought them out.

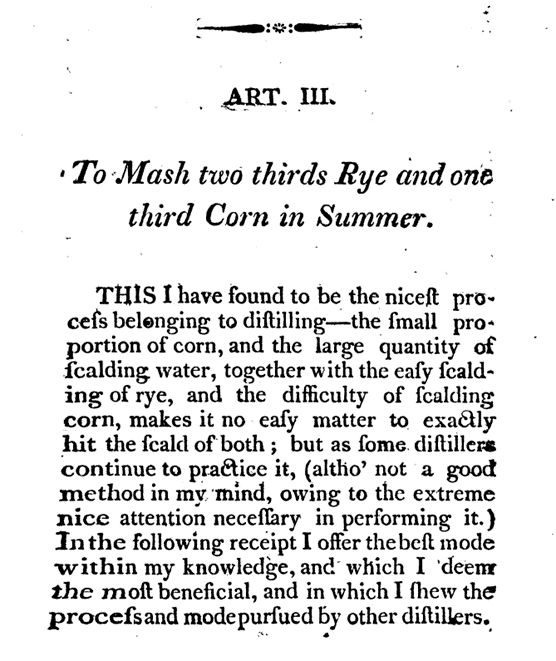

We must also consider that before Prohibition, America’s distilling industry had been molding and transforming apprentices into master distillers for over 6 generations by the time Prohibition shut it all down. They had been adjusting their methods, learning how to adapt their craft and upgrade their equipment. The equipment and the knowledge that came from understanding how to use it properly was an art in itself. They had worked with many different types of stills and were alive to see the industry develop. Many of the old distillers in the early 1900s had seen it all! Fire heat on a still meant knowing how to keep a consistent flame with wood or charcoal. Understanding how a fire’s heat affects the distillate and the run is not a modern concern but understanding heat, how and when and in what amounts it should be applied to a mash, is a hands-on learning experience. These men understood steam-heat and plumbing. They witnessed upgrades in mash tubs and fermentation tanks and how the agitators could stir and mix different grain bills differently. I was actually just speaking with a modern distiller that recently bought a new mash cooker and the agitator had to be redesigned- it was designed to cook mashes with more corn and not for rye. The stirring blades meant to agitate the mash and mix it well during the cooking process were not offset enough. They needed to create the shearing force necessary to move that viscous rye mash properly but the machine was designed for a bourbon mash with more corn. Even in 1809, Samuel M’Harry of Pennsylvania wrote in his Practical Distiller about how adding corn to a mash makes the cooking process easier.

Easier, however, did not mean better. Rye whiskey was the first style of whiskey to gain a national reputation for excellence. It wasn’t the only style of whiskey being made, but it remained the most valuable in the trade. That means that no amount of added cost or hassle could stop its manufacture, and it remained the preferred style of whiskey made by hundreds of independent distillers across Pennsylvania and Maryland. Even with easier methods and techniques out there, men chose to make rye.

There were also peculiarities about rye in early mashbills that made American whiskey special in the world. I’m not sure if you could say it made things more difficult, but it did require unique know-how on the part of early distillers. The first distillers to arrive from Europe attempted to sparge or lauter their mashes (separate the grain from the distillers’ “beer”) in the manner they had done back home. Once settled in and all set up to distill whiskey, European immigrants quickly learned that mashes containing rye would not separate well. Whiskey making in America would require a distiller to operate his still “on the grain” instead of from a “wash.” Immigrants called it the “American style” of whiskey making. Even if an immigrant distiller was well-versed in his trade when he arrived on American shores, he had to apprentice with an American distiller before getting his start and finding success in the trade here. This understanding that there were peculiarities that needed to be learned gave rye distillers secure positions in their jobs once hired. Many new distillery owners in the late 1800s would brag about their distiller AND where he was trained in their newspaper advertisements.

Perhaps the greatest loss to the modern distiller when it comes to the manufacturing of rye whiskey is the loss of the traditional still set up that once produced it in such large quantities. Most distilleries in Pennsylvania required a chambered still to make their whiskey. The fermented mash would be pumped from a beer vat or holding tank in the still house basement up into the chambered still on the first floor for its first distillation run. That still was monitored at all times. In some cases, the vapor would move from a three chambered still directly into a long, copper worm. In other distilleries, the alcohol vapor from the chambered still would be condensed and loaded into a large, copper doubler to be refined and then make its way into the coiling, copper worm. In the end, a separator would allow an operator to assess the high wines and determine whether to send it back into the doubler or into the cistern for collection. The maintenance and technical skill related to the operation of these stills is long gone. There are no three chamber still experts remaining today. Mr. Todd Leopold of Leopold Brothers Distillery in Colorado commissioned a three chamber still designed to mimic the one that once sat in Hiram Walker’s plant in Peoria. He represents the only knowledgeable three chamber still operator in the United States but has only been operating the equipment since 2015-2016. Vendome copper works had never engineered one before. The three chamber was a flavor extraction machine. Without it, a modern distiller could not hope to recreate a pre-Prohibition rye whiskey.

An interesting thing to note is that the famous Michters/Bombergers Distillery in Schaefferstown, Pa had a three chamber still until it was dismantled in the late 60s- early 70s to make room for a new column still. The last master distiller at Michters, Dick Stoll, knew that it was there during the time that the distillery was known as Kirk’s Pure Rye Distilling Co. Mr. Stoll never operated the three chamber but noted that C.Everett Beam may have at some point. He was, however, the only distiller in the country in the 70s and 80s to operate both a column and a pot still. Michters owned a “barrel a day” copper pot still that was run to demonstrate traditional distilling methods for whiskey tourists. Even in the 70s and 80s, the country looked to Pennsylvania to make rye whiskey because that’s where the experts were. In keeping with the addition of the column still (which would have been blasphemy to a pre-pro PA distiller, by the way), the mashbill on the rye whiskey produced at Michters was just over 60% rye, about 30% corn and malted barley. Making rye whiskey was no longer allowed to be as expensive to produce as it used to be. By then, rye whiskey had become a forgotten art.

There is too much missing from the “how to distill rye whiskey” manual, though many modern distillers are making the best with what they’ve got and with what they know. I’ve heard of distillers adding butter or lard to rye mashes to keep down foaming. I remember listening to Dave Pickerell (Rest in Peace, Dave) say that he brushed lard around the top of a hogshead to keep his mash from foaming over! I’ve even read that those early distillers would add a shovel full of hot ash from the still’s firebox directly into the mash. Some old-time distillers malted all their rye while others toasted the rye grain before mashing it in. Some swore that certain yeasts strains were preferable for rye. I’ve also heard from modern distillers that the best way to handle rye mashes is to use enzymes to convert as many sugars as possible. Now don’t get me wrong. Rye is a tough grain. But it rewards the distiller by providing the most flavor that any grain could hope to contribute to a whiskey. There’s a reason the bourbon makers call rye “The Flavoring Grain.” Everyone knows that rye is the tasty part of any good American whiskey. Is it more difficult to work with? Perhaps. Is there probably tons of missing information once available to rye whiskey distillers that we don’t have access to anymore? Absolutely. We are about 75-100 years removed from the the old ways of making whiskey. Hopefully, with enough research and engineering, we can find a way to re-learn enough of what was lost and marry that to what we know now to make the finest rye whiskey the world has ever seen.