As I continue to dig into the origins of aged American whiskeys and into how far back their production goes, I continue to discover very interesting practices and find hints into the history of barrel aging.

The first item to be considered when talking about “old whiskey” in a historic context should probably be barrel entry proof. We put so much stock into it now, but was barrel entry proof always a consideration? What exactly was barrel entry proof if we’re talking about whiskey made before Prohibition? And what does “before Prohibition” mean, anyway? Are we talking about 1910? Or 1870? How about 200 years ago? Well, guess what? It differed over time- as you might expect.

In the early 1800s, whiskey went into barrels for two main reasons- storage and transportation. The finest liquors available to consumers were imported European products. These imported barrels with their battered and patinaed surfaces contained madeira wines, brandies and cognacs, Irish whiskeys and scotch, etc. – all of which were in high demand 200 years ago…and bringing good revenues for tradesmen.

High price points encouraged entrepreneurial men in the rectifying business to not only repackage and sell the contents of these imported barrels, but also to mimic these foreign spirits by adding flavors and other additives to locally-made distilled products (the base spirit varied). The value of imports also encouraged early attempts to truly mimic the mellowing of spirits made in the US using American-made cooperage. Liquor men invested in the future of their businesses by establishing their own maturation warehouses. There, they could not only store the older barrels they’d purchased, but could also store new barrels filled with locally produced new-make “high wines”. Newly filled barrels could be mellowed before being used in blends or for use in some future endeavor. While it is likely that most of these early efforts were not “barrel-aged” spirits as we think of them today, there is no doubt that some of it must have been matured on purpose- at least in part. Large hogsheads meant for shipping were usually packaged as high wines (higher proof) because most buyers wished to purchase in bulk and rectify their contents anyway- either by diluting it with water or by altering the spirit with additives.

Large barrels were repackaged into smaller containers for retail purposes, always packaged with the intent to dispense. In other words, a retailer would not have been filling smaller casks with anything other than proof spirits barreled at “drinking strength”. So…in most cases, the bigger the barrel, the higher the proof, and the smaller the barrel, the lower the proof (approx. 50% alcohol). The rectifying trade drove the liquor market. Rectifiers represented the big, wholesale buyers of bulk product coming from the distilleries (production facilities) AND represented the retail end of the market, which sold directly to the consumer. It was the rectifier, not the distiller, that determined barrel entry proof for the barrels that went into warehouses for aging/maturation. As soon as steam heat was introduced in the early 1800s, it would have been the rectifiers and liquor tradesmen that embraced the use of steam heat in warehouses to the greatest effect.

How do we know that larger sized barrels used for shipping via boat in the early 1800s were full of “high” proof spirits? Well, it just didn’t make financial sense to do it any other way! Unless the barrel was going directly to a buyer at proof strength (100 proof or thereabout), tradesmen would want to get as much quality product to market in as few containers as possible. This kept down shipping costs for the producer (more weight shipped on a boat/ship, the higher the export costs) and put more valuable product in the hands of the purchaser. Once government gaugers had alcohol hydrometers at their disposal, there was no fooling anyone anyway, so there was no reason to lie about the barrel’s contents.

After 1807, in cities like Philadelphia, Baltimore, and New York, acts of legislature required that all spiritous liquors being offered for sale must undergo inspection by a gauger before being sold. Those packages, by law, must have been marked as one of following: underproof, 1st proof, 2nd proof, 3rd proof, or 4th proof.” (More info on grades of proof HERE.)

In Harrison Hall’s “The Distiller,” he explains how a distiller is better off barreling his whiskey at as high a proof as possible because “as the proof is raised, the proportion (of profit) increases in his favor.” There was no question that a distiller/rectifier would make more money by putting higher proof spirits into their barrels. These barrels were sold, traded, and shipped by river to any number of nearby or distant markets, or stored in warehouses during the interim. The longer a barrel sat, the older and more valuable it became. An old 3rd or 4th proof whiskey barrel carried a higher price tag. Remember, there was no bonding period before the Civil War era, so a barrel could sit in an individual’s private liquor warehouse for any undisclosed length of time. These “old barrels” sold at market might contain any level of alcohol content, but the most valuable seem to have been the old 3rd, 4th, and 5th proof spirits with the highest percentage of alcohol in them. (As a side note, most of the whiskeys I’ve seen advertised as old 5th proof barrels have been imported Irish whiskeys.)

Most of these early barrels were being sold to rectifiers. We tend to think of distillery-owned bonded warehouses as being the place where whiskey has always been stored and aged until those barrels were fully matured and ready for bottling (and for sale to the public), but that was not always the case. It was the rectifying businesses that used to own the large maturation warehouses. The rectifiers, especially those with retail licenses and storefronts, were the ones storing, distributing, repackaging, and selling whiskey to the public. Each liquor business catered to a different clientele, and their products reflected that. The beauty of all these business variations within the industry was that they all created more opportunity for experimentation and discovery within the industry! Over the years, rectifiers were able to determine which types of barrels containing various types of spirits aged better under different circumstances. We begin to see the 30-40 gallon barrel become the common barrel size utilized in warehouses. 40+ gallon barrels (tierces), though not legally standardized, had become the norm by the mid-19th century.

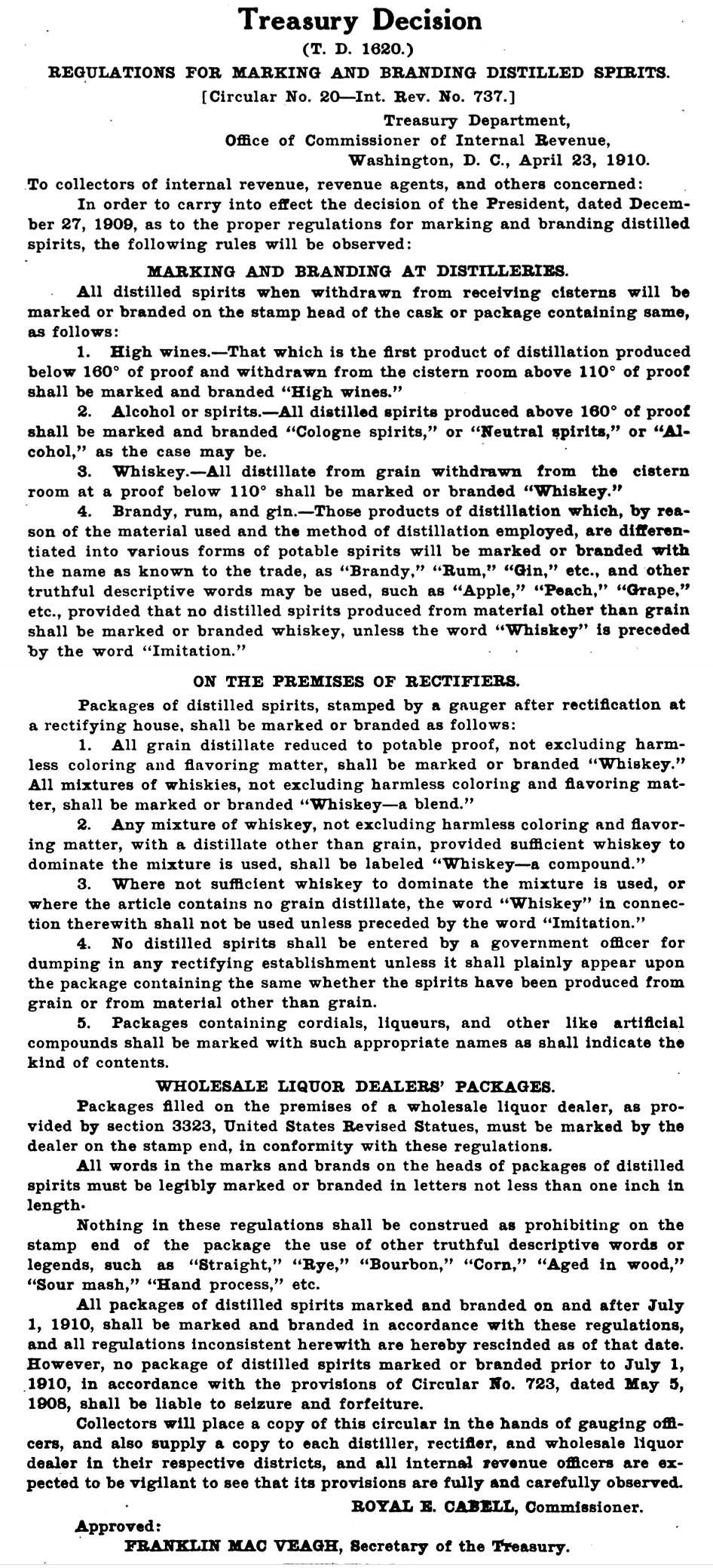

America’s first excise taxes, which were imposed in the late 1700s, necessitated the creation of government approved gaugers manuals. Those manuals, however, were only geared toward measuring the volume of a barrel’s contents. By the mid-1800s, when the excise tax returned, we start to see much more attention focused on the percentage of taxable alcohol in each barrel. By the 1870s, the US government began assigning gaugers and storekeepers to every active distillery in the country, and those men oversaw the transfer of finished distillate into every barrel. What came off the still was emptied into the distilleries’ closely-monitored cisterns. The contents of the cisterns went right into barrels, and those barrels went right into government bonded warehouses. Each distillery was different and had a different configuration of equipment in its still house, so each distillate would have had a different final proof off the still, as well. This meant that the “proof off the still” became the barrel entry proof that went into the distillery’s 40-gallon barrels.

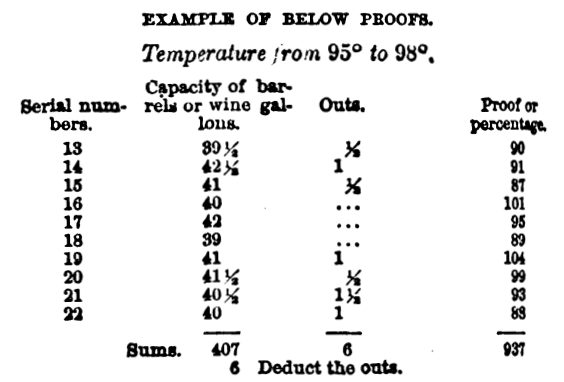

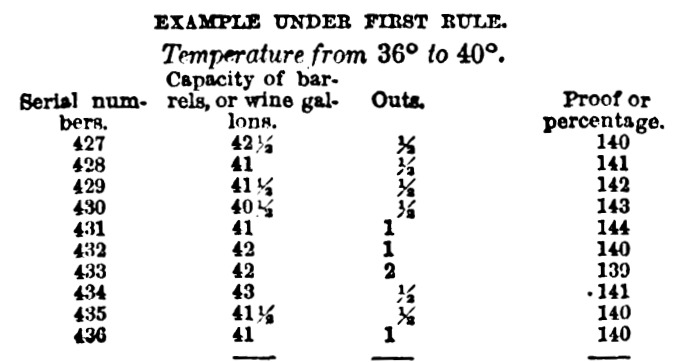

These charts are from an 1867 copy of the “Internal Revenue Record and Customs Journal: A Weekly Register of Official Information on Internal and Customs Revenue.” It contained up-to-date information for government gaugers. You can see that barrels containing 90-103 proof spirits were considered “under proof” and that 40-gallon barrels were filled with much higher proof spirits during the mid-19th century.

These charts are from an 1867 copy of the “Internal Revenue Record and Customs Journal: A Weekly Register of Official Information on Internal and Customs Revenue.” It contained up-to-date information for government gaugers. You can see that barrels containing 90-103 proof spirits were considered “under proof” and that 40-gallon barrels were filled with much higher proof spirits during the mid-19th century.

Again, the barrel size may have differed in each distillery, but the barrels went directly into the government’s bonded warehouse. The barrel size was not a concern to the gauger, because he was obligated to measure the contents of each barrel, regardless of its size. The warehouse, which was necessary, was legally obligated to be built on the distiller’s dime, but its contents were under strict supervision by the government. The gaugers were the only men that could gain legal access to the buildings. The distillery owner could remove the barrels only after the taxes were paid, and the whiskey was allotted a 1-year bonding period before those taxes must be paid to the government. Once paid, the barrels could be removed and sold, or moved to a “free warehouse” on (or off) the premises for additional aging. Most additional aging would take place in a rectifier’s warehouse (off premises) once the barrels were purchased. Rectifiers could, under the supervision of their own gaugers, bring the whiskey to a different proof or adjust the proof by adding or blending-in other whiskeys or neural grain spirits. A rectifying license allowed them to redistill the contents of the barrels they purchased and/or adjust them as they saw fit. To be clear, the distilleries were production facilities, and the rectifiers were the folks more in control of what we would call “barrel entry proof” for the whiskeys matured over time. In many cases, distillery owners were approved for both licenses by local courts (a distilling license and a rectifying license), so many were managing the contents of their own barrels. After 1867, however, distillers were no longer allowed to sell their products at retail- only wholesale- out of their distilleries. Many distillery owners, who had been selling directly to the public before the law change, began to seek out retail locations near their distilleries or in nearby cities where they could sell directly to the public. Many chose to own and manage both!

An interesting thing to note here- It was in the early 1870s that gaugers began to recognize that evaporation and changes in proof were taking place in the barrel. (The government was always behind the curve on these things! Distiller’s didn’t mind their ignorance because it seemed to benefit them😊) A famous Pennsylvania distillery owner named John Gibson was brought up on charges in 1873 for selling whiskey that was higher in proof AFTER the taxes had been paid! There had been no conclusive evidence until this point that whiskey even evaporated from barrels, and the government was skeptical that evaporation took place at all! The tax law was adjusted accordingly, and taxes were raised in 1875.

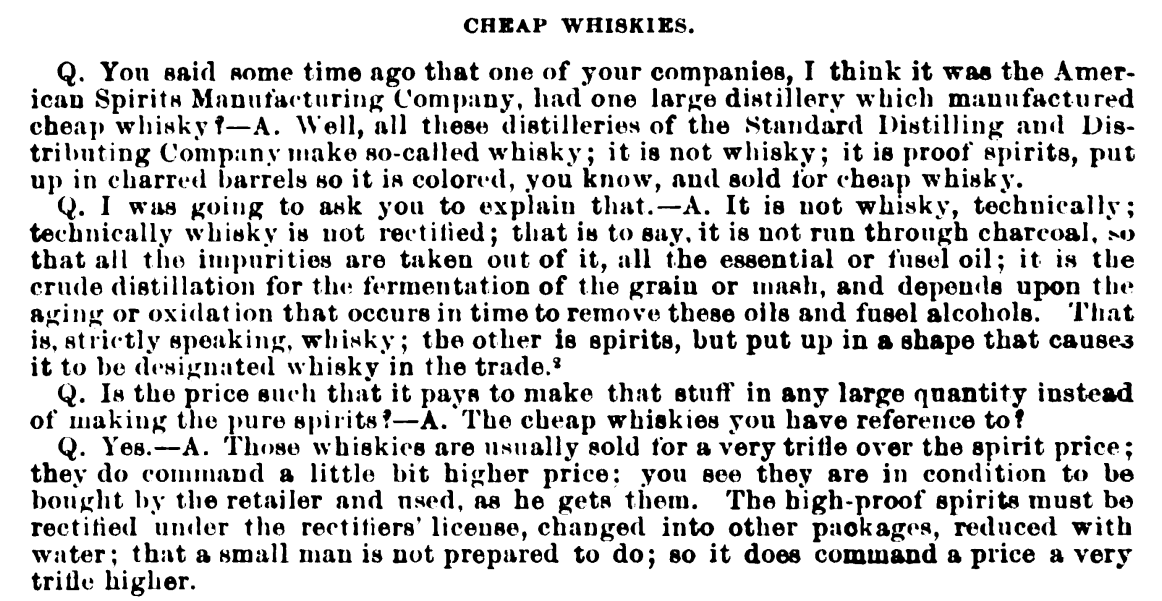

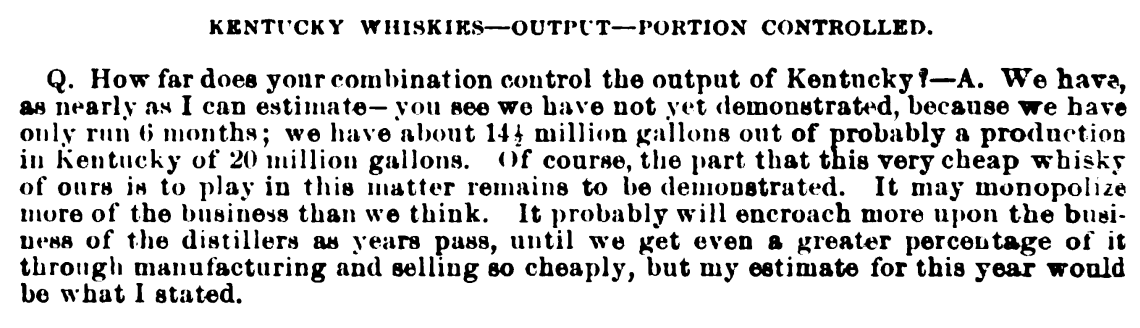

We don’t really start seeing legal discussions around the topic of barrel entry proof until the “Whiskey Trust era” -during the 1880s and 90s. (If you’re unfamiliar with this timeline, please read more- The Whiskey Trust and how it began as the Distillers’ and Cattle Feeders’ Trust) The Whiskey Trust was in the business of controlling distillery outputs and whiskey prices, so their concern with manufacturing in bulk sparked this new interest in entry proof. Historians often note that the Whiskey Trust was broken up after the Sherman Anti-Trust Act was made law, but the group known as the “Whiskey Trust” simply reformed itself into a new corporation- now known as the American Spirits Manufacturing Company (and its 3 main subsidiaries). This transition is where we begin to see pure rye and straight whiskey makers complaining about “the manufacture of cheap whiskey.” This “cheap whiskey” was not so different from their own products in its manufacture. Where it differed was in the use of column stills and the level of barrel entry proof. Column stills manufactured a higher proof spirit than the pot stills and chambered stills that had been more commonly employed throughout the whiskey industry. In a general sense, the distillers of Kentucky had not yet embraced the column still in the 1880s. That was…until the Whiskey Trust began to exert its influence there- either directly or indirectly.

One of the first distillers to install the column still for making straight whiskeys in Kentucky was J.G. Mattingly in 1888. It is unclear exactly when the distillers of Kentucky began to replace their three chamber stills, copper pot stills and other steam heated patent stills with the column. The column still was not a new invention, but it had not been embraced by distillers of barrel aged spirits, otherwise known as “pure” or “straight whiskeys.” Distillers of pure ryes and straight whiskeys stubbornly maintained their “old school methods” which sought to keep an advantageous amount of fusel oils in the distillate. The only segment of the industry that utilized the column still (until the 1880s) were the rectifiers who sought to remove all traces of fusel oils and create a distillate free of “impurities.” So why then would Kentucky’s distillers wholly embrace the use of a distilling apparatus that was used almost exclusively by rectifiers? My theory is that the transition took place as the distilleries in Kentucky were bought up and began being managed by the ex-Whiskey Trust, a company very concerned with keeping costs down and bringing production levels up.

A column still distillate was, no doubt, very different from what the Kentucky distillers had been producing before. The distillate coming off of the column stills and going into the gauger-overseen cisterns would have been a cleaner, higher-proof product. This modified spirit and its higher proof going into the cisterns seems to be the impetus toward distillery owners wishing to drop the proof of the final distillate before entry into the barrel. Before the advent of the column still in straight whiskey distilleries, the distillate off the still had been low enough to go right into the barrel- without dilution! Each distillery likely had its own target proof off the still. They had refined their distinct newmake spirit over the course of many years, and it seems likely that their aim would have always been to recreate that distillate each time they upgraded the machinery in their distillery. It is equally likely that there were certain exceptions that had to be made with each move toward modernization. But the transition to column stills must have been a leap of faith for many Kentucky distillers.

To provide some context into this transition to column stills and how Kentucky almost universally transitioned, let’s quickly look at how this transition happened in the first place.

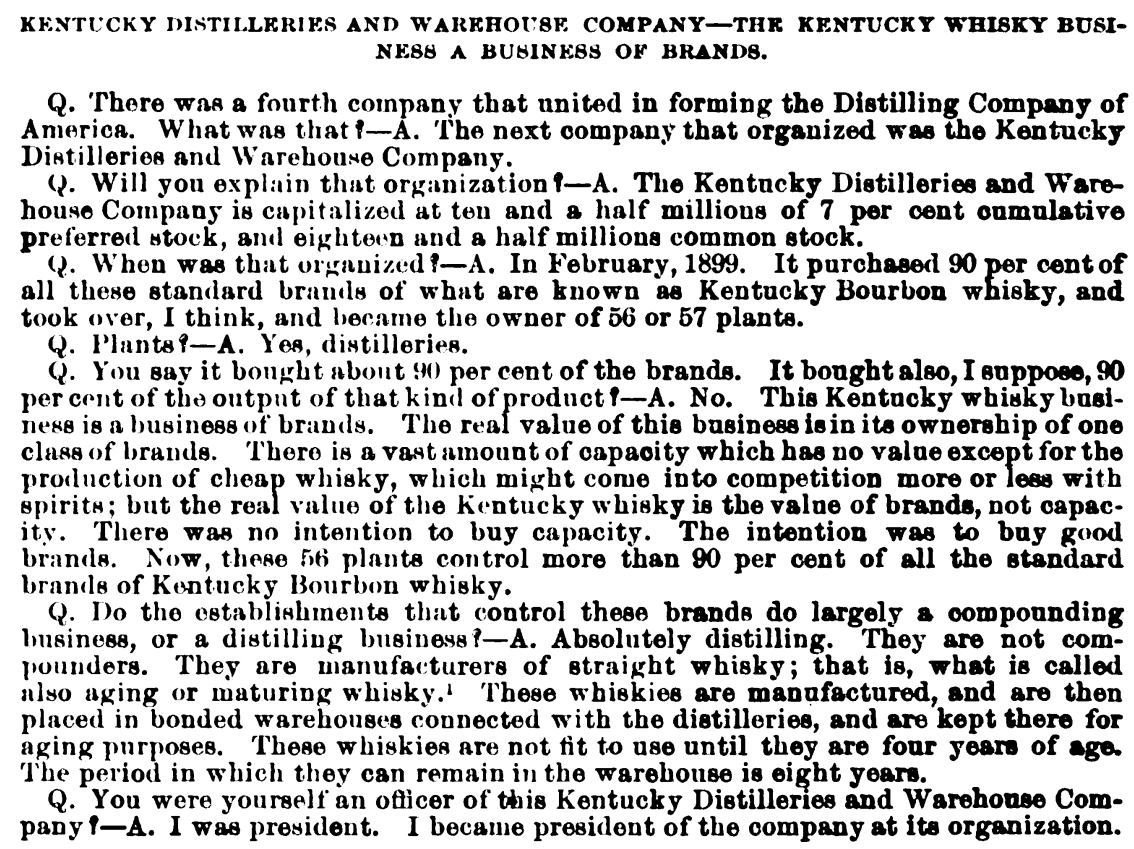

In 1899, the American Spirits Manufacturing Company had acquired (through its subsidiaries) about 90% of Kentucky’s valuable brands and 57 of the state’s distilleries (about 70% of KY’s whiskey production) and, from them. created the Kentucky Distilleries and Warehouse Co. As the ASMC grew, it became even more actively involved in creating a legally sanctioned monopoly of the liquor industry. The plan was to create a nation-wide liquor interest known as the Distilling Company of America. They had purchased most of the Kentucky distilleries which would represent the straight whiskey portion of their portfolio. In 1900, an inquiry was performed before the U.S. Industrial Commission into the whiskey combinations that had been formed from the old Whiskey Trust. (The Industrial Commission was a United States government body in existence from 1898 to 1902. It was appointed by President William McKinley to investigate railroad pricing policy, industrial concentration, and the impact of immigration on labor markets, and make recommendations to the President and Congress.) The commission’s main concern was the monopolistic trends that were taking place with companies that were still behaving like trusts. The liquor industry, one of the most valuable for the government’s income through tax revenue, while very competitive on paper, was clearly being consolidated into a handful of parent companies. One in particular was actively attempting to control the country’s liquor production and manipulate prices. The main target of the investigation was the newest iteration of the old Whiskey Trust from the 1880s- the American Spirits Manufacturing Company and its growing number of subsidiaries.

The American Spirits Manufacturing Company already controlled the interests of the old Whiskey Trust which represented the largest plants based in New York and throughout the “Western” states. These interests covered their blended and rectified spirit portfolio, as well as other younger, barrel-aged whiskeys. The ASMC was unable to acquire the third and most valuable piece of their business plan- the pure rye whiskey distilleries in Pennsylvania and Maryland. Without this acquisition, their original plan to form the Distilling Company of America collapsed, but the temporary failure did not end their efforts to fulfill their original goal. During the inquiry before the Industrial Commission, Mr. Edson Bradley, the President of American Spirits Manufacturing Company (ASMC), answered questions while explaining how his company was not a trust at all, how controlling the industry would be good for the country’s economy, and how he could solve all the government’s problems with the liquor industry. He was quite convincing, too!

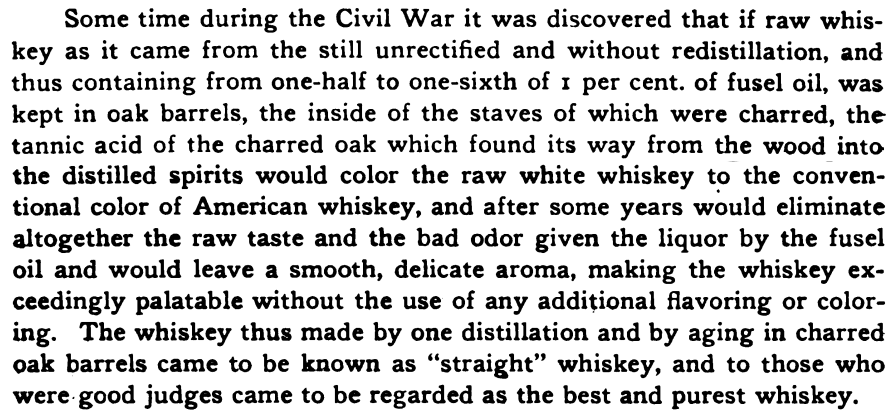

Journalists were not convinced by the ASMC’s efforts to portray itself to Congress as a benign and helpful organization, so they attacked the company’s monopolistic ambitions in print. Newspapers continued to call out the newly formed Whiskey Trust and all its lobbyist’s machinations. The 1900 inquiry by the Industrial Commission was just the beginning. The Food and Drug Act, followed by the Roosevelt-Bonaparte-Wiley Decision and the Taft Decision, attempted to legislate the legitimacy of whiskey and calm the onslaught of liquor lobbyists swarming Washington DC. After President Taft put his very informed foot down (Taft had been a gauger and understood the industry better than most), the laws FINALLY began to legislate barrel entry proof for the industry- though not entirely and not the way it is today. Taft clearly describes the practice of making straight whiskey in his decision, but he is only truly addressing the segments of the liquor industry that are pressing the issue of “what is whisky” to begin with- the straight whiskey interests based in Kentucky that are owned by the KY Distilleries and Warehouse Co. and its parent company, the ASMC.

Here are those regulations that were the result of Taft’s Decision They were drafted in April 1910:

You can see in the wording of the Treasury Decision that the gauger’s marks/brands/stamps on barrels (as they related to whiskey after 1910) were either going to be labeled “whiskey,” “high wines,” “cologne spirits,” “alcohol,” or “neutral grain spirits.” Clearly all of these grain-based distillates with all of their corresponding proofs were still going into barrels. You can also see from the Treasury Decision that rectifiers were the licensed parties that reduced higher proof spirits to a potable level (90- just above 100 proof). It is this “potable level” that has dictated how barrel entry had been conducted for so many years. If distillers meant for the whiskey in their barrels to be dispensed “as was,” it would make sense that that is how they chose to prepare their products for barreling.

By the nineteen teens, the Anti-Saloon League was a force to be reckoned with and their influence on the Webb Canyon Act (an act to prohibit interstate commerce into dry states) was a blow to the liquor industry. In March 1912, representatives from liquor interests all over the country pushed for legislation to support their enduring, reputable businesses. They needed the government to take into consideration all the new discoveries that had come to light such as evaporation and changes in proof and update the tax laws accordingly. A real concern for “the method and character of storage of whiskey” was stressed. A hearing with the Ways and Means Committee revealed that the standard size barrel that was being used after the turn of the century had grown and the quality of the timber had decreased. In most cases, barrels had grown to 48 gallons, and kiln drying was beginning to cheapen the quality of white oak staves being used for cooperage. This, of course affected how barrel entry proof would affect the spirit.

The most important law to affect barrel entry was the Federal Alcohol Administration Act of 1935. The Federal Alcohol Administration, which was formed in 1933 after Repeal, devised the first “Standards of Identity” for American whiskeys. These regulations, for the first time, included industry-wide standards for barrel entry proof. As much as it may have been necessary to lay out those standards of identity after Repeal, the unmistakable influence of powerful liquor interests were written all over those new standards.

Class 2: Whiskey

(a) Whiskey is an alcoholic distillate from a fermented mash of grain distilled at less than 190 proof in such manner that the distillate possesses the taste, aroma, and characteristics generally attributed to whiskey, and withdrawn from the cistern room at not more than 110 and not less than 80 proof, whether or not such proof is further reduced prior to bottling to not less than 80 proof and also includes mixtures of the foregoing distillates for which no specific standards of identity are described herein. Rye whiskey, bourbon whiskey, wheat whiskey, corn whiskey, malt whiskey, or rye malt whiskey is whiskey which has been distilled to not exceeding 160 proof from a fermented mash of not less than 51% rye grain, corn grain, wheat grain, malted barley grain or malted rye grain, respectively, and also includes mixtures of such whiskeys where the mixture consists exclusively of whiskeys of the same type.

(b) Straight whiskey is an alcoholic distillate from a fermented mash of grain distilled from a fermented mash of grain distilled at not exceeding 160 proof and withdrawn from the cistern room at not more than 110 and not less than 80 proof, whether or not such proof is further reduced prior to bottling to not less than 80 proof, and is-

(1) Aged for not less than 12 calendar months if bottled on or after July 1, 1936, and before July 1, 1937; or

(2) Aged for not less than 18 calendar months if bottled on or after July 1, 1937, and before July 1, 1938; or

(3) Aged for not less than 24 calendar months if bottled on or after July 1, 1938.The term “straight whiskey” also includes mixtures of straight whiskey, which, by reason of being homogeneous, are not subject to the rectification tax under the Internal Revenue Laws

Those 13 years of Prohibition had given the Whiskey Trust all the time and opportunity it needed to gain the most powerful position in the whiskey industry. The American Spirits Manufacturing Company may have failed to morph into the Distilling Company of America, but Prohibition gave its board of directors the opportunity to manipulate almost every aspect of the industry. The powerful men associated with the old Whiskey Trust were finally able to assemble the largest liquor company the country had ever known- National Distillers. The influence of the Big Four (National Distillers, Schenley, Seagram’s and Hiram Walker) was present in the legislation crafted after Repeal. Unsurprisingly, post-Repeal laws favored the largest manufacturers and placed any smaller companies looking to start anew at a disadvantage. What was once considered “under-proof” whiskey or “potable strength” whiskey was now legally the barrel entry proof for the larger barrels being used in Kentucky. “Distillation proof” for straight whiskey was as high as 160 proof (as it still is today), but the expectation was that the distillate would be cut with water in the cistern before being barreled. even if that high a proof “off the still” would have been considered “high wines” before Prohibition, and would have been barreled at that strength by distilleries. New legislation eliminated bulk sales which eliminated any need to sell “high wines” at wholesale to rectifying houses. After Repeal, barrels would only used to age whiskey in government bonded warehouses for bottling purposes.

A quote from the Chairman and director of the Federal Alcohol Control Administration, Joseph H. Choate, during a 1935 hearing in Washington DC is revealing. He explains that the issues which arose after the Taft Decision were applicable in the post-Repeal era, as well. Choate felt that National Distillers, the largest of the Big Four and owner of half of America’s aged whiskey stocks, was rewriting what whiskey was allowed to be without a man like Taft to stop them or tell them otherwise.

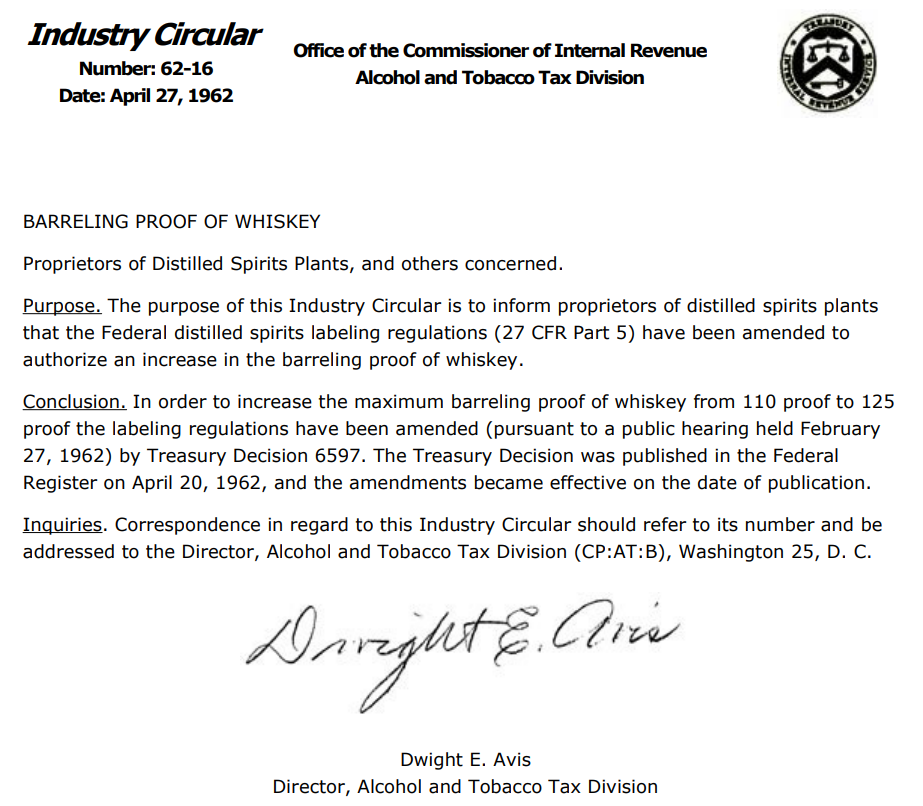

Today, we know that barrel entry proof has evolved from the 1935 description of “not more than 110 and not less than 80 proof.” In 1962, (through the influence of Seagram’s) the rules were changed again to legally allow distillers a new limit of 125 proof. There doesn’t appear to be limit for how low an entry proof can be…which is odd. I suppose as long as your whiskey ends up above 80 proof after aging, you should be good! This change in the 60s meant that distillers could use fewer barrels to craft the products they desired in a reasonably short time. Of course, by the 1960s, almost all of the heated warehouses had been eliminated and almost all the three chamber stills and pot stills that had once been so commonly used to make pure ryes and straight whiskey were long gone.

Today, barrels are very heavily relied on for their flavor contributions to the American whiskeys we drink. Did the column still strip away a lot of the heavier chemical constituents of whiskey and affect the way whiskey aged in barrels? Did we lose something by allowing a lighter distillate to be made into straight whiskey? Did we forget the heated warehouse and the chemistry of what happens in those barrels that were once stored there? “A Study of the Changes Taking Place in Whiskey Stored in Wood,” research conducted by C.A.Crampton and L.M.Tolman between 1898 and 1907, clearly show that almost every sample used in the comparative study was drawn directly from the cistern, yet each sample was almost identical in proof (around 100 proof). Nowhere in the study does it mention that the samples were altered before filling the barrels. Did the distillate get diluted before entry, and if so, why was it diluted? Was that the norm at the time? Why isn’t it mentioned in a scientific study? Was it simply to maintain a constant for comparison or was it the industry standard to barrel in this way? It certainly does not seem likely that all distilleries barreled at 100 proof. The study was funded by the Bureau of Internal Revenue to better understand how to best tax the distilling companies, so it seems likely that adding water had become the job of the government gauger in the cistern room. But then, why wouldn’t the distilling industry have been more insistent upon diversity of product? What is there to be gained by having such similar products to your competition?

Much more research should be done to determine how distillers and rectifiers were managing their barrels before Prohibition. I don’t know if I’ve answered my questions about barrel entry proof or just created more questions in the process. I hope these facts are at least helpful in inspiring others to look into the matter. Barrel entry proof has never been clearly spelled out by the industry before the 1930s, so there’s much more to investigate. Perhaps a more detailed investigation into the origins of barrel proof are in order, if only to help modern distillers work out how to proceed in their own distillation practices. It might also be helpful in pointing out that distilling practices have never been set in stone and the more we place legal restrictions on practices that provide advantages to some and not to others, we limit the variety of American whiskey that can be made available to consumers. Perhaps low barrel entry proof helps a lighter distillate but hinders a heavier, denser distillate. Here’s hoping we keep digging into America’s forgotten distilling practices!