The question is inevitably asked whenever a discussion about pre-Prohibition American whiskeys comes up: “We we romanticize pre-Prohibition whiskey?” Industry folks tend to be very skeptical about “the old methods.” Their doubts are understandable, though. There aren’t many references that easily explain how whiskey used to be made in the mid-to-late 19th century. There are few options for whiskey writers to immerse themselves in a traditional distilling experience and even fewer opportunities for them to sample their way through a line-up of antique whiskeys- certainly not one that would represent the diverse flavor profiles present in 19th century whiskeys. The modern craft distilling industry may be busy experimenting with “old techniques” and laying claim to traditional methods of distillation, but they aren’t being instructed by pre-Pro master distillers! There are loads of articles constantly being published about how some new whiskey is “a game changer” that harkens back to its pre-Prohibition roots, so it’s easy to see how one might become skeptical. Too many of these “traditionally-made whiskeys” being made today are receiving mediocre reviews and too many whiskey enthusiasts have sampled badly preserved antique bottles of whiskey. Most writers I’ve had the privilege of speaking with have wrapped our discussions on pre-Prohibition American whiskeys with these questions:

“Is it possible that your opinions of pre-pro rye whiskey are a bit romanticized?”

“Isn’t it true that modern whiskeys are inherently superior? I mean, wouldn’t you agree that technology is vastly improved and product consistency is just…better?”

“If rye whiskey was so great, why isn’t it around anymore?”

All great questions, of course. (As far as that last one goes, that’s a long discussion and you can read about that HERE.) Our modern, pre-conceived notions of what whiskey should be are not in line with what whiskey USED to be. It’s not an easy notion to dispel. Let’s address some of this skepticism.

The history of pre-Prohibition American whiskey is largely misunderstood. Or, at least, not understood in context. Unfortunately, the American whiskey drinking public has been learning about American whiskey history through a lens focused singularly on Kentucky bourbon. Bourbon history is NOT the genesis of American whiskey history, so we’re left without context. Think of it as trying to encapsulate an appreciation for American history by taking a single semester history course on World War II. There is NO DOUBT that you’d have gained incredible insight into what made America what it is today, but, without a broader understanding of American history before the war, you’d be missing some context. One can’t understand the modern whiskey industry without learning about how bourbon came to be popular in the first place. You can’t understand bourbon without understanding how the whiskey industry existed outside of Kentucky- for the rest of the country. And let’s be clear- the rest of the country’s whiskey makers were very busy manufacturing their own unique spirits using their own state’s traditions and methods. Just because we aren’t as familiar with Pennsylvania’s pure ryes, Indiana’s apple brandies, Missouri’s imported and blended whiskeys, California’s fortified wines/brandies, or Peoria, Illinois’ late-19th century distilling empire, does not mean that those traditions were any less important pieces of America’s distilling history. Now, I could go on all day about the differences between modern and pre-pro production processes (the inferior grain varietals in use today, sweet mash vs. sour mash, still technology and how different still designs were employed to make very different products, the devastating loss of accumulated knowledge that came from 250 years of distilling traditions that were annihilated by Prohibition…), but all those distinctions are rooted in preference and could spark debate. One can always argue over flavor preferences and what caused them- a technically superior, mature product with more flavor compounds may not be favored by a modern palate, for instance- and that’s a fair argument. However, there is no debating real changes that have taken place over the last hundred years. The cost-to-profit ratio of making whiskey in America has grown over the last century- a shift toward favoring profit over production techniques. There is no denying that it was more expensive to make rye whiskey and brandy than it was to make corn whiskey, bourbon, or neutral grain spirits. If you factor in the cost of using more expensive equipment and grain, tack on the additional fuel costs of heating warehouses, and consider the added expense of funding your own product distribution, it is very hard to compare the cost of doing business before and after Prohibition. The corporate distilling interests that survived Prohibition picked the bones of what remained after Repeal and built a new normal. They cut almost every corner that pre-Prohibition distillers deemed necessary. So, even if you’ve had the opportunity to taste a pre-pro whiskey or two, or whether you’ve seen merit in old production techniques, that small window into historic whiskeys is insufficient. Whiskey history has been spun into fairy tales by so many advertising campaigns that it’s hard to know what to believe. Marketing departments certainly romanticize whiskey! But they have little incentive to back up their elaborate stories with facts or site historic references. It’s their job to sell whiskey, not educate the consumer.

It should be obvious that bourbon whiskey history is NOT rye whiskey history, but that reality has been muddled. For many decades, bourbon distilleries have been making rye whiskey on their column stills for a few short weeks every production year. Their marketing teams have been spinning tales about the history of old rye whiskey brands. They were never going to be ideal ambassadors for the history of rye whiskey, especially when there was little incentive to remind people how little the ryes they were manufacturing had in common with pre-Prohibition ryes (or with any traditionally made rye whiskeys, for that matter). Bourbon history has its own incredible (and largely forgotten) history that was co-opted by corporations (foreign and domestic). Bourbon has also become quite different than it used to be, but at least it’s being manufactured by people that genuinely love and respect the product! Rye deserves the same level of respect and commitment to its excellence. It shouldn’t be painted as bourbon’s doddering old ancestor just because its young, hip parent companies bought the old brand names and control the conversation.

Bourbon and rye followed a similar timeline after the Civil War, but the foundations of American whiskey making were laid in the Northeast. This, at least, is non-debatable. Rye and bourbon both morphed into brown spirits in the early 1800s, but the earliest of America’s aged whiskeys were rye whiskeys, not bourbons. Early texts specifically name Philadelphia and Baltimore as the origins for aged whiskeys becoming popular in America (and in Europe and Asia). New York City quickly took over as the hub of the eastern rye whiskey market by the 1880s, and this can be seen by the migration of large firms into New York (if not their home offices, then major satellite locations were established for whiskey firms based in Philadelphia, Cincinnati, St. Louis, Chicago, Baltimore, etc.). One can also see the Whiskey Trust’s influence in the consolidation of these liquor businesses. The 1880s and 1890s were marked by overproduction and market fluctuation for American whiskey producers. This era created a definitive line between “straight bourbons,” “pure ryes,” and rectified spirits within the trade* even if these distinctions wouldn’t be addressed by the government for another decade. A power struggle between the big and bigger producers was underway. Lobbying and advertising for one style or another were being used by companies as a means to win market share…Now, during an interview, this is usually where someone invariably brings up the rectifying industry and the “industrialization of American whiskey.” They’ll ask, “Well, wasn’t Pennsylvania and Maryland more industrial and more focused on rectifying?” This little chestnut is the biggest hurdle when attempting to convince someone that old whiskey was better once upon a time. RECTIFYING is NOT a four letter word, folks. Though you’d never know it if you read modern whiskey histories…

No, Pennsylvania and Maryland were not more focused on rectification than any other state. They were not any more industrial than any large distillery operation in Kentucky. PA and MD made “pure ryes” and Kentucky made “straight bourbons.” Both were “unadulterated” barrel aged products.** Every “wet” state had liquor firms and blending houses that manufactured rectified spirits. The only reason people don’t know that is because, again, bourbon histories are the only ones we hear. It is in the interest of modern marketing firms to promote bourbon because those are the companies with the most money to spend on marketing. Rye whiskey, brandy, cordials, and rectified liquors have no choice- they have to take the back seat to bourbon.

I don’t know how to say this more clearly…Rectification was a legitimate and a much more historically relevant business than any other segment of the liquor industry. Before mature, barrel-aged whiskeys became profitable investments for liquor firms and bottlers, white spirits were rectified/blended with other ingredients to improve their taste and increase their value to the consumer. Rectified spirits may have had additives or been filtered through charcoal to remove unwanted off-flavors. Once brown spirits gained market share, the rectifying industry wholly embraced them while continuing to manufacture gins and other flavored or botanically-infused spirits. They might redistill an unsatisfactory whiskey or filter it or blend together favorable barrels. They also possessed the ability (and the money) to bottle their own products which the distillery owners usually did not. Once rectified whiskey was embraced by the Whiskey Trust in the 1880s and used as a means to produce huge amounts of lower quality whiskey, the rectifying trade would never be the same.

The Whiskey Trust flooded the market and stirred the pot. What had been a 200 year old trade involving thousands of licensed producers (many with excellent reputations) across the country, was now branded a villainous collective by the straight whiskey lobby. Their constant, slanderous propaganda worked so well that we still go on today about how rectifiers were putting spit and battery acid into whiskey before the straight whiskey firms were able to save us all! Now, don’t get me wrong, there have always been bad players within the American industry. Usually, those bad players are either trying to trick you with false information into making a sale, or they are a soulless corporate entity that doesn’t see anything wrong with injuring their customers. But we’re talking about generations-old businesses here! Rectifiers, to put it simply, were liquor men that purchased their liquor stocks from someone else. They either blended or modified those spirits to create something they knew their customers would want to buy. You do not keep a business with a downtown address in a major U.S. city by poisoning your customers. These rectifiers owned large warehouses that held large quantities of accumulated liquor stocks- both domestic and imported. They also had the ability to bottle their products, ship their products, and create highly valued brands within the industry. They were seen as a threat to the Whiskey Trust’s dominance over market share. The propaganda launched during the early 1900s against rectifiers was almost entirely funded by the reformed Whiskey Trust, managed by its public relations and advertising firm in New York. The adulteration of liquor was absolutely a real issue during Prohibition when distilling went underground, but when distilling was a legitimate and very lucrative business BEFORE Prohibition, the rectifying world was not as much a threat to public health as it was to the profitability of straight whiskey firms owned by the reformed Whiskey Trust.

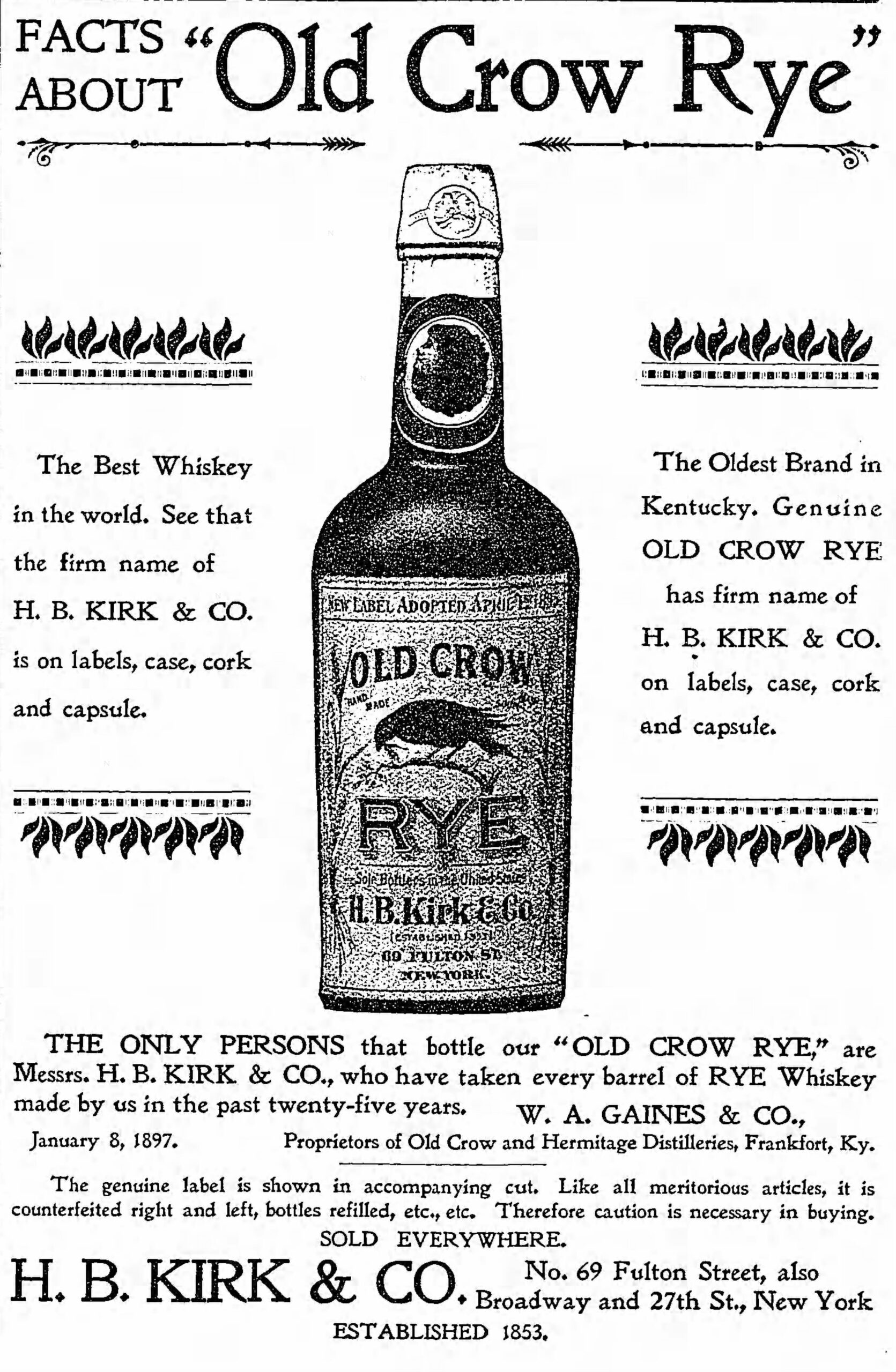

Once we understand the truth about rectifiers and realize that the trade was highjacked by the Whiskey Trust, we can begin to appreciate that rectifiers were an important part of the whiskey trade. Many of those pre-pro whiskey bottles with recognizable brands like “Old Crow” and “Mount Vernon” are bottled under names like “Hellman & Co.” or “Cook & Bernheimer” instead of . It seems complicated, but it’s all just two sides of the same coin. The whiskey trade has always been a competitive industry, but products that stand out as being superior have always been sought out. Companies knew then (just as they know now) that mimicking a well-known product could be profitable, but consumers ultimately determined which would succeed. Winning the trust of the public was just as difficult then as it is now. The interesting thing is that there were so many more private bottlers back then. There were more competitive production facilities making unique products that not only had contracts with these private bottlers but also sold barrels to hotels, saloons, and restaurants. Small producers didn’t have to bottle their own products as they do today, but they often helped build the clientele of a hotel or drinking establishment. And to top it all off, far more Americans drank whiskey in the late 19th and early 20th century, so they would have been far more attuned to what they would consider “a good whiskey.”

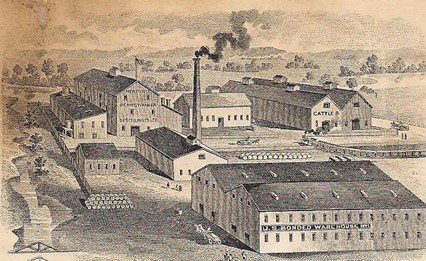

The variations in whiskey before Prohibition must have been all over the flavor chart. A single distillery’s product could have been different depending on who was buying it and who was selling it. Think of the variations that were possible! Think of how different the same mashbill from a bulk manufacturer like Ross & Squibb Distillery (MGP) can present depending upon which whiskey company buying the product repackages it! The skill of a blender, the manipulation of the spirit through finishes, or the addition of any flavors or additives would make all the difference in the world. Before Prohibition, certain products stood out as superior to others and earned such excellent reputations that they were plagiarized. Liquor companies were forced to file lawsuits against these copycats to protect the trademarks of their treasured brands. Hospitals sought out brands that had earned reputations for purity and excellence. Older whiskeys could be marked up in price because the demand created by consumers allowed it. With many hundreds of distilleries and thousands of retail liquor locations across the United States all vying for market share, there was an incredible variety of options and a very wide range of quality in these products. Not every whiskey was going to be great, but quality products were sought out in such a highly competitive atmosphere. Issues with adulterated liquors were, however, found in the world of “cheap whiskey”. This cheap whiskey segment of the industry, by the way, was the purview of the Whiskey Trust! Bottom shelf liquor was easy to make, could be made at much lower margins, and there was always profit to be made in the end. What the Whiskey Trust did not want was competition. By the time Prohibition came along, consumer choices became largely irrelevant, almost immediately.

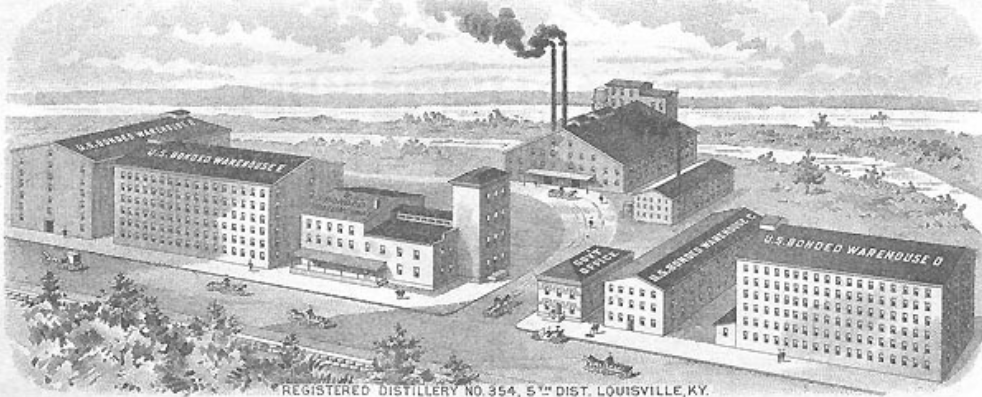

When Prohibition arrived, the number of licensed bottlers took a nosedive. The number of warehouses licensed to store the “government’s whiskey” (taxes were still due!) went from 800 in 1917 to about 30 in the mid 20s. The nation’s whiskey and its brands were consolidated. The hundreds of distilleries that held whiskey stocks in their warehouses were forced to move those barrels into concentration warehouses after 1922. The owners of these concentration warehouses, once they were able to take ownership of it all (using questionable methods), began bottling what was left of it all in 1927 under the few brand labels they owned. So whether you were a small distillery in central Pennsylvania or from a large distillery in Illinois, chances were good that your whiskey was going to be bottled as a Kentucky-based brand.

The reputations of old brands belonging to defunct distilling companies were co-opted by corporate interests through the purchase of these brands. The whiskey was good, but it no longer belonged to the distiller that made it to begin with. During Prohibition, between late 1929 and 1932, only a handful of distilleries were even allowed to distill the whiskey that would become bottled-in-bond medicinal whiskey after 1934. Most of those distilleries not only shared the same or similar production techniques, but they were also using the same sources for bulk grain! The dwindling stocks that remained from those defunct distilleries was bottled up and sold as quickly as possible. Not only would those distilleries never make whiskey again, whatever whiskey barrels remained with their names and reputation linked to it was bottled under a different label by an unrelated company. The whiskey that WE THINK we know as being pre-Prohibition ryes from Pennsylvania are often not even from Pennsylvania. And when they are from Pennsylvania, they may be labeled as being made by one distillery but actually be from a completely unrelated distillery. It gets confusing, yes…the point I’m trying to get at here is that many of the folks reviewing the quality of pre-Prohibition whiskeys don’t even know what they’re drinking! It’s hard to agree that “modern drinkers are romanticizing pre-pro whiskeys” when so many of the people that have tried it and have given their opinions of it are so often wrong about where the whiskey was even from. And yes, it is important to know that because different whiskey distilleries used different processes and made very different styles of whiskey. Forming an educated opinion on product quality kind of requires knowing who made it to begin with.

Occasionally, a whiskey reviewer will describe a pre-Prohibition bottle and declare it to be terrible. “This must have gone bad or something,” they say. There are MANY reasons why a bottle might have gone bad over the last hundred years. Even the Commissioner of Prohibition bragged that less than 10% of medicinal whiskey in warehouses was adulterated in any way- as if that were worthy of bragging rights. 10% is a big number, especially when you consider how little Prohibition-era whiskey remains to this day! That negative review may also have been due to the whiskey being a blend of some very old whiskey (that was well past its years) being blended with younger spirit. By the time whiskey barrels were being bottled in earnest in 1927, some of the whiskey in those concentration warehouses was too far gone. It may have lost potency through evaporation. It may have been bootlegged liquor with an exceptionally well-make fake label! Any number of things could have happened to that bottle of whiskey while the barrels were being transported from one place to another, or while a government gauger was being paid to look the other way. Even if a bottle was full of delicious whiskey in 1930 doesn’t mean that 100 years of storage didn’t harm or alter it. But even after 100 years or more…the good bottles? They can be unbelievably delicious. These survivor bottles are why people that seek vintage whiskeys swear by them. Reviewers of those bottles ask, “What were they doing different back then to make this so good?” or “Why is that bottle so bad and this one so good?” I would argue that is definitely worth knowing the history of the bottle/distillery/brand before forming any finite conclusions.

I’m happy to TRY to explain why a bottle of pre-pro whiskey might be so superior to anything made today or what may have caused that depth of flavor, but my answer would fall short. We just don’t know everything they knew. So much knowledge about the process of making pre-Pro whiskey has been lost to time. (I’m crossing my fingers that someone finds more distiller’s notebooks one day that will reveal helpful minutia and insight into their production methods.) I know that many will argue that modern processes are superior, but I can’t trust that opinion when it comes from industry insiders that didn’t even know what a 3 chamber still was until a few years ago. I think when we come to a collective realization that there was more competition in the market, there was a great deal more varied expertise within the industry (both on the part of the producer and the consumer), and there were literally businesses with experience going back over 6 or 7 generations that they built their reputation upon…well, you don’t have to take my word for it. It’s not bias or romance. It’s just common sense.

*This is an important distinction because the acceptance of “straight” as a designation for bourbon was only ever accepted as a definition “within the trade” before Prohibition. It is often said that the Taft decision made straight whiskey a legal definition, but this is NOT ACCURATE. Taft explained the distinction between whiskey and rectified whiskey- allowing them both to continue to exist as unique styles of “whiskeys” -even as the straight whiskey interests made moves to eliminate their competition. Taft explained that the trade understood the difference and that the law was only necessary to stop false advertising and bickering.

**It should be pointed out that there were no real legal limitations on putting additives in straight whiskey before Prohibition. Bottled-in-bond whiskeys were free of adulterations, but if bottled during Prohibition, you were forced to take their word for it. The strict adherence to bottled-in-bond regulations loosened after 1920. The Medicinal Spirits Act of 1927 specifically included language saying that the “Secretary of the Treasury may by regulation permit the addition of spirits of the same kind (whether or not such spirits are the same season’s production and produced by the same producer) to other spirits, in order to raise the proof to standard.” While the Medicinal Spirits Act was not approved by the Senate to become law, there was a good deal of side-stepping of the 1897 Bottled in Bond law made possible by the Secretary of the Treasury after 1927 when bottling of many different barrels that qualified as “medicinal spirits” became necessary. This is why you see Prohibition-era bottles that read “a blend of straight whiskeys” from one distillery but bottled in another location with green BIB tax strips. It is unclear when the rules regarding “bottled-in-bond” in the TTB’s Title 27 were updated. (perhaps in 1937?)