S.S. Brumbaugh

Near New Enterprise, South Woodbury Township

Bedford County

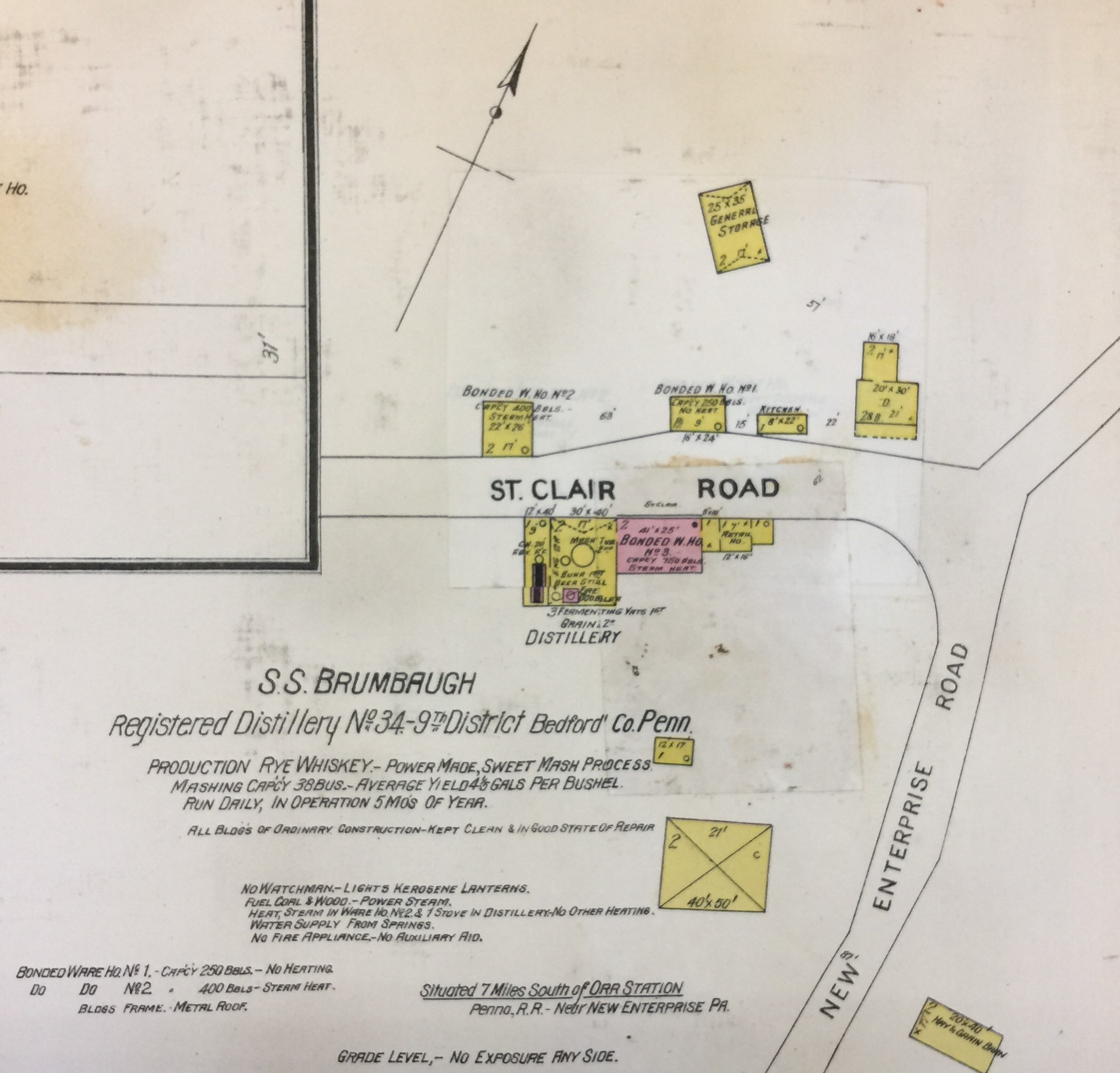

RD# 34

9th District

“Brumbaugh whiskey, bottled expressly for medicinal use,” was so well known that people began to identify Dunning Mountain as “Brumbaugh Mountain”—a name attached to the site a generation after the distillery closed.”

(Bible, Axe and Plow. Ben F. Van Horn, Sr. 1986)

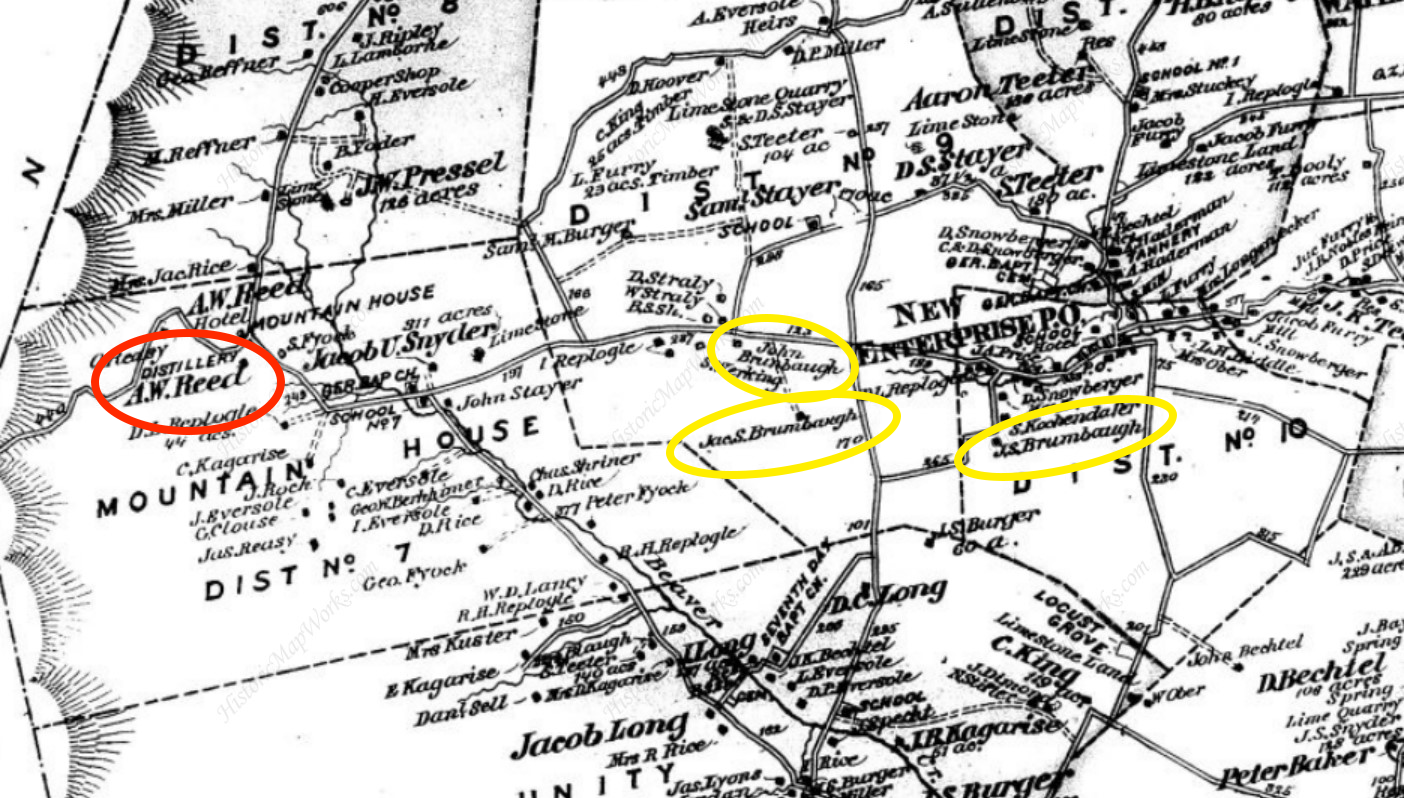

The Brumbaugh family was one of the oldest in Bedford County. The family’s patriarch, Johann Brumbaugh, immigrated to America from Germany in 1750, settling first in Maryland. Johann’s grandson, John, moved to Pennsylvania from Hagerstown, Maryland and was an early pioneer of South Woodbury in Bedford County. He finally settled on 800 acres of wild, unimproved land near Morrison’s Cove, east of Dunning Mountain. The family may have had distilling knowledge from their native Germany, but they did not produce whiskey commercially until 1880.

Simon Snyder Brumbaugh, the third generation of Brumbaughs to live in Morrison’s Cove, would make the Brumbaugh name synonymous with excellent whiskey. He purchased his distillery at the foot of Dunning Mountain from a well-known hotel owner named Aaron W. Reed. Reed originally built the distillery in 1860 and had already been producing rye whiskey there for 20 years, but Simon would upgrade and modernize the facility, changing the rye whiskey produced there.

Simon became postmaster of his own hamlet in 1894, naming the post office “Brumbaugh.” The endless supply of cold mountain spring water and plentiful supply of local grain made his location ideal.* He ran his distillery for 5 months of the year.

Simon’s son, Oscar, was born around the time that he bought his distillery, so it would be years before Simon could teach his son the trade. In the meantime, Simon employed a distiller named John Shaffer. By the early 1900’s, however, father and son were working together at the distillery. (Most of the information about the Brumbaugh Distillery’s production techniques were sourced from this segment of the distillery’s historic timeline.)

Brumbaugh’s Distillery accepted grain deliveries from local farmers. Their mash consisted of 5 parts unmalted rye grain to one-part roasted barley malt. Simon and Oscar Brumbaugh cultured their own yeast, often selling it to other local distillers in need, and used it to ferment their rye mash for 3 days. (This likely varied depending upon the weather and ambient seasonal temperatures.) The fermented mash then passed through one of two double-chambered wooden beer stills (possibly both) before being refined in a fire-heated doubler to achieve a 180-proof finished distillate. (While 90% alcohol would not meet the legal requirement for whiskey today, this would not have been unusual before Prohibition if they were producing rectified spirits.) It appears from recorded descriptions of the distillery that the whiskey was aged in very large, used cooperage- 90-104 gallon butts. It is likely that there were a combination of containers used at the distillery that varied in size. Legally, the containers had to be at least 40 gallons to be sold by a distillery holding a wholesale liquor license after 1893.* Before going into the barrels, it was also noted; “…the Brumbaugh brew was colored artificially with a low-grade “A” sugar which was burnt to a caramel. An enticing color was the result. The longer the whiskey was aged, the deeper the color became.” This description reinforces the idea that the Brumbaughs were either rectifying their own spirits or selling their distillate to retailers who would rectify and label their containers as “Brumbaugh whiskey.” The Brumbaugh’s “pure rye whiskey” was sold at the distillery by the gallon; their 2-year-old sold for $2.25, a 6-year-old for $2.50, and a “very old” (over 6 years) aged rye for $3.00. The 3 bonded warehouses on site held a total of 1400 barrels- 2 were heated with steam, but the smallest was not. The smaller warehouse may have been a “free warehouse” used to store tax-paid whiskey that had been taken “out of bond.” Steers were also raised on the property. Their feed of spent mash from the distillery made them very valuable for sale as meat.

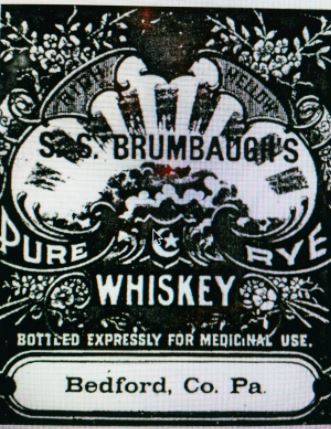

Most of the whiskey sold by Brumbaugh was sold “by the barrel” or “by the jug.” Bottle sales, which were not only uncommon with liquor firms until the late 1800s, they were not an option for distilleries. Since 1867, distilleries had been banned from retail sales and were limited to wholesale sales of “no less than than one gallon.” The distillery shipped its barrels to wholesale buyers via railroad. Simon and Oscar employed “abstaining men” to make the deliveries because they found some of their teamster delivery drivers “had found a method for getting a quart or two from the barrels while on their way to the railroad station.” From October to June, the distillery employees began work at 5am and kept busy all day churning out 2 to 3 barrels before their shifts ended. Some workers were paid with room-and-board and free liquor. Oscar, who was known to abstain from whiskey, served as salesman for the company and traveled to taverns and hotels with samples in bottles with white lettering that read “Brumbaugh’s Pure Rye Whiskey.” Any promotional decanters that were sold were meant to be displayed prominently with “S.S.Brumbaugh- Pure Rye Whiskey- Bedford Co., Pa” etched in gold on the glass.

Simon S. Brumbaugh died at the age of 64, leaving Oscar to manage the business. Oscar Brumbaugh operated the distillery right up until 1917 when the Lever Act ended whiskey production in the U.S. before Prohibition. In fact, the night before Prohibition went into effect, local residents pooled their money and purchased a common barrel, which they poured at a community gathering that night, toasting the last remnants of “Brumbaugh’s best.” After Prohibition went into effect, the remaining contents of Brumbaugh’s warehouses were shipped to Philadelphia’s concentration warehouse. The last remnants of the Bedford County distillery were destroyed in 1961.

Anecdotal evidence from locals interviewed in the late 1980’s suggests that bottles of Brumbaugh whiskey still survived in the homes of local townspeople three quarters of a century later. Brumbaugh’s bottles and jugs are highly sought after collectibles today.

*Bedford is known, even today, for its limestone springs and for the resort that was established there to take advantage of the site’s “healing waters.” For centuries, Pennsylvania’s native population used the mineral springs for their curative powers, a custom that they shared with local doctor John Anderson in the 1790s. Anderson prescribed specialized treatments for afflicted guests, who journeyed from around the world to experience the healing waters. To accommodate the growing number of patients, Anderson built an inn in 1806 using stone quarried from the mountain adjacent to the springs. Over the next century, the resort added amenities, including one of the first golf courses and indoor pools in America.

**The act of June 20, 1893 act gives distillers the right to sell liquors of their own manufacture in original packages of not less than forty gallons without requiring them to take out a license under the act of 1891.