J. Mathias Distillery

Manor, Pa.

Westmoreland County

RD# 22

23rd District

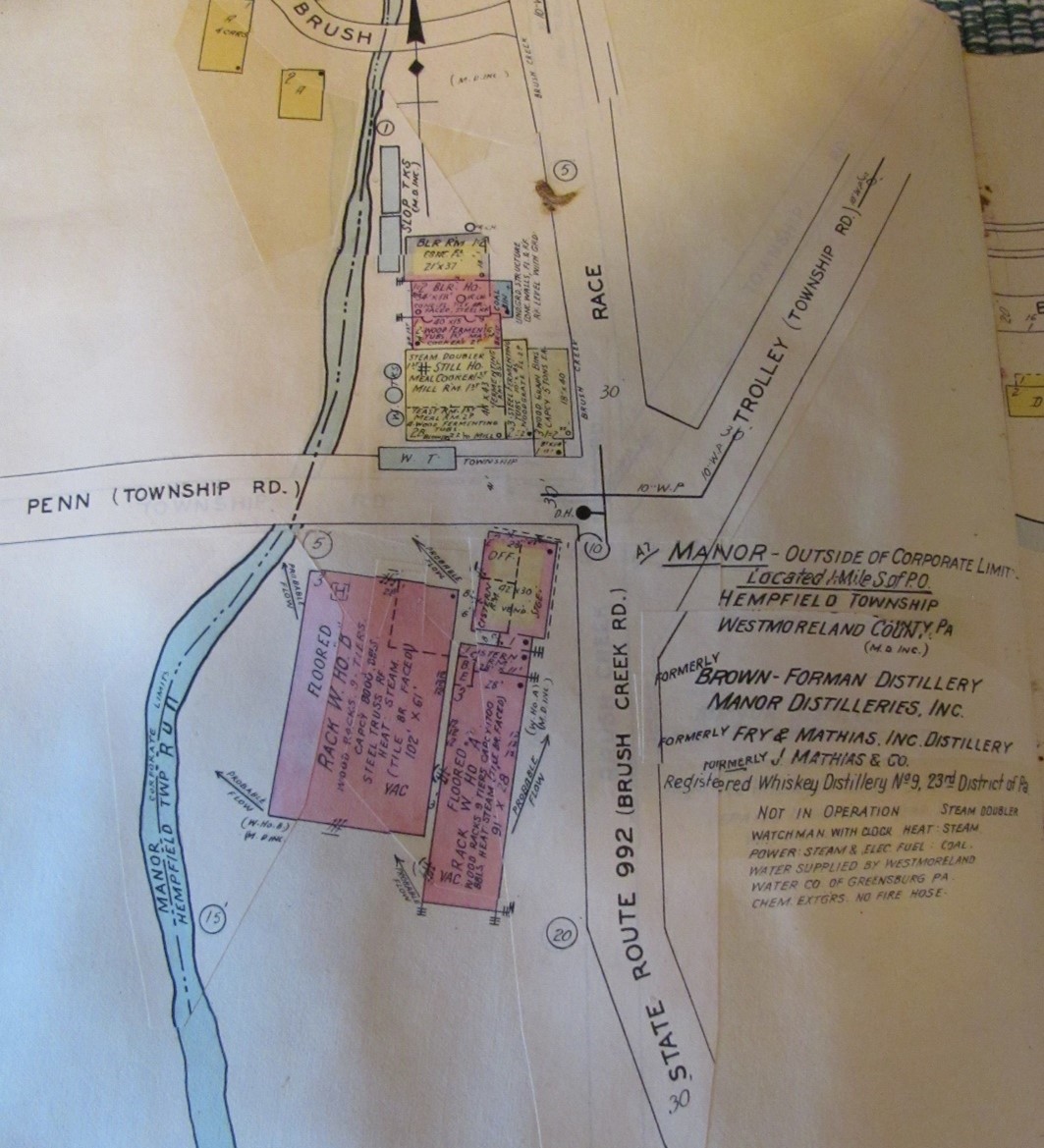

The small borough of Manor, Pennsylvania in Westmoreland County was once home to the incomparable Fry & Mathias Distillery. It is tragic that this distillery and its legacy have been largely forgotten. Those citizens of Manor that do realize that a distillery was once central to their town’s economy have only vague recollections of what it once was. With origins stretching back to before the Civil War, Fry & Mathias was still active as a distillery into the late 1940s (possibly early 1950s). In fact, its final owner was the famous Brown Forman Company, owners of Jack Daniels and Old Forester whiskey brands (most likely for bottling and warehousing purposes). Even after its founders were long gone, new owners kept the distillery’s original name knowing they could build upon the reputation for excellence Fry & Mathias had earned. Unfortunately, these new owners often chipped away at that reputation. The distillery’s legacy and influence, however, with all its ups and downs over the course of a century, left an indelible mark on Pennsylvania’s rye whiskey trade. The history of Pennsylvania rye whiskey is incomplete without the story of Fry & Mathias Distillery…tucked away in its little town just east of Pittsburgh.

Manor, Pennsylvania became an ideal place for a distillery in the 1850s when the Pennsylvania Railroad opened a station there. The town was originally a part of Denmark-Manor, one of the manors (estates) procured by the heirs of William Penn. The settlers of the town were known as the “Manor Dutch” as most of them were of Pennsylvania Dutch origin. While Manor remained mostly unsettled, forested acreage during the early 1800s, the railroad brought access to markets in Pittsburgh and Philadelphia which encouraged growth. The Manor Stock Yards, during the mid-19th century brought drovers and their cattle from the surrounding counties to sell their herds. Manor Station gave cattlemen access to the railroad which allowed them to tap into distant markets that had previously been out of reach. Commerce meant thirsty travelers and created an ideal place for Dominic Fry to set up his small distillery.

Dominic Fry, born on August 6, 1825, came to America from Germany. He had been a tin smith in his native country and followed his trade in America while also taking on work in carpentry and cabinet making. He purchased a small distillery in Manor as a young man and ran that business for a short while before moving 15 miles west to McKeesport, Pennsylvania, a bustling town beside the Monongahela River.* In 1877, Fry returned to Manor and bought back his distillery, though this time, he was not on his own. He formed a partnership with Jacob Mathias, a successful farmer who had been running a mercantile business in Madison, Pa. The two men rebuilt the distillery in 1882, and Dominic brought his eldest son, Warren Gress Fry, in (if he hadn’t been there already) to help with the distillery. Their new building, unfortunately, was all but destroyed in a fire the following May. Thankfully, their bonded warehouse was unharmed in the blaze. Of the 250 hogs that were being raised on the property, all but 40 were saved. The loss was estimated to be anywhere from 15 to 25 thousand dollars. Fry & Mathias held insurance for $14,750, but most of that was for the warehouse with only about $2500 covering the contents of the still house. The local paper, the Argus, described the whiskey supply of the “Manor Dutch” being “somewhat abbreviated.” Undeterred, Fry & Mathias rebuilt their stillhouse, and conducted a successful business for several years with Dominic Fry as the senior member of the firm.

When Dominic Fry died in 1885, Jacob Mathias became sole owner. The year after Dominic’s passing, Jacob partnered with his son, Joseph Mathias, and his son-in-law, Andrew Jackson Good, of Penn Township. A.J. Good was married to Dominic Fry’s daughter, Sophia. While the distillery’s capacity was 33 bushels per day, it exported its “Old Westmoreland Rye” and “Old Manor” whiskeys as far west as Missouri. The brothers-in-law diversified their income by conducting a large dairy and creamery in Manor as well.

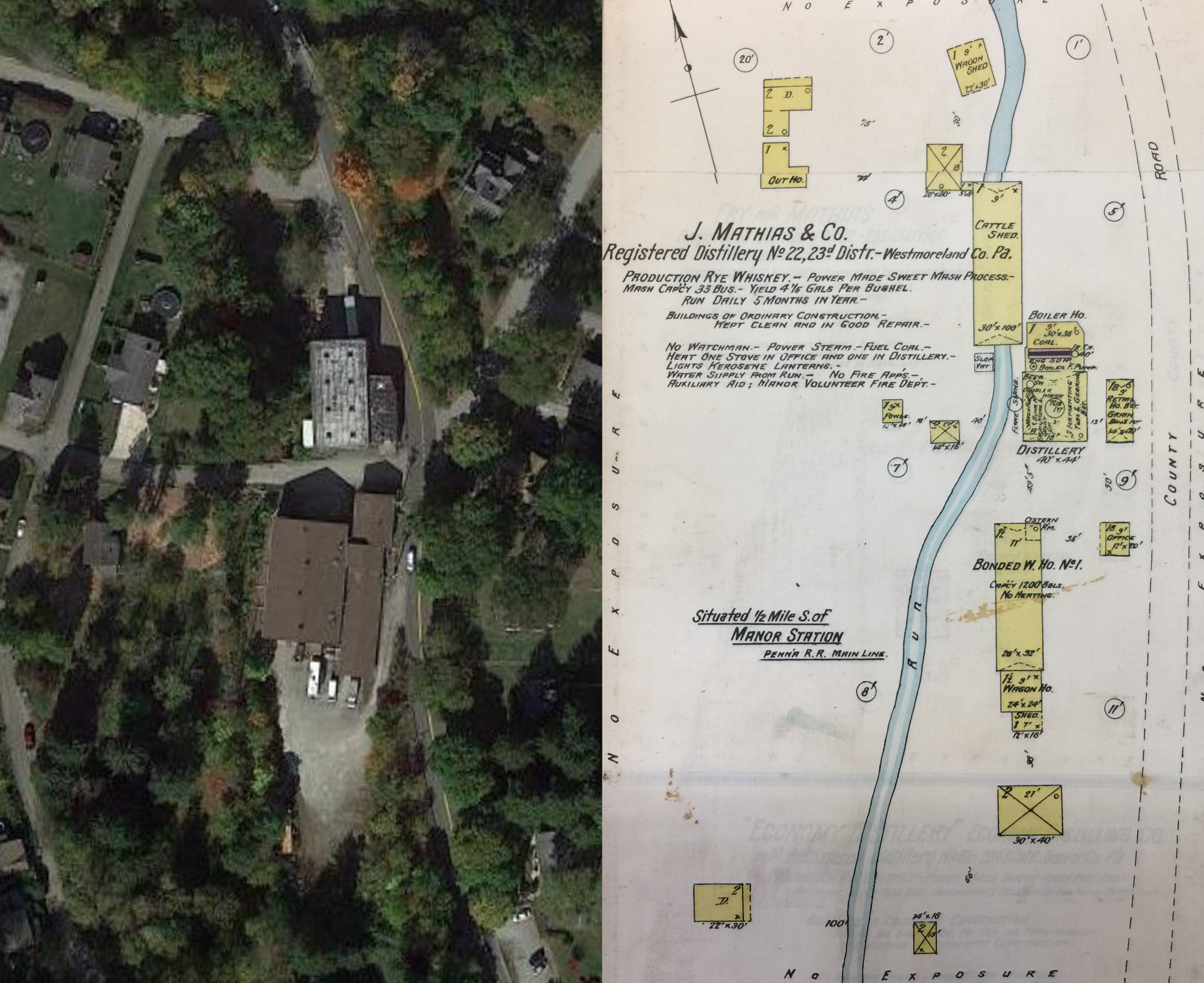

In 1903, Jacob, who had been recognized as being the oldest citizen of Manor, died at the age of 85. Joseph and Andrew Good resumed the business. The year after Jacob’s passing, J.Mathias & Co. contracted the construction of a 3-story 40’ x 100’ warehouse to be built of concrete blocks. At a cost of $12,000, the new warehouse would hold up to 3,000 barrels. (This warehouse is still standing.) Joseph Mathias maintained his role as president of the Mathias Distilling Company for the next 12 years while also serving as president for the First National Bank and the Spangler Brewing Company.

The Fry & Mathias Distillery continued its production of rye whiskeys under the growing pressures of the temperance movement until Joseph Mathias’ health began to fail. Joseph died of complications from lung cancer on April 3, 1916 at the age of 65. The Food and Fuel Act of 1917 shut down all distilling and whiskey production the following year, and Prohibition ended any possibility of A.J. Good continuing the business. Andrew Good lived until 1925, but his death marked the end of any connection the company had to its original owners.

After Repeal, in January 1934, 3 men from Pittsburgh chartered Fry & Mathias, Inc. with a capital stock of $10,000, though they had already been busily refurbishing the old Manor distillery property for eight months. The incorporators of this new company were John T. Butler, C.B.Butler, and E.K.Brogan. John Butler, the company’s president, had been manager of the E.V. Babcock football team in Pittsburgh around 1920 and was well remembered for it. He brought in C.F. “Bud” Wymard, a former Fordham football star to act as salesman. Butler knew that “Bud’s” charisma would make him an ideal candidate for the job because he would be a great draw for new customers. Wymard had connections to old teammates like Frank Frisch (“The Fordham Flash”) and used that relationship to tease the press about bringing him to a game next time the Cardinals were in Pittsburgh. Butler also brought in Warren Fry, Dominic Fry’s son, who was now nearly 70 years old. W.G. Fry’s 40 years of experience running the stills at Fry & Mathias were invaluable in retaining product continuity and in maintaining the marketability of the distillery’s famous name.

In 1936, John T. Butler sold Fry & Mathias to David H. Stern for $200,000. David Stern had been a near-beer distributor during Prohibition and managed an apartment hotel in Squirrel Hill, Pittsburgh. He entered the liquor business immediately after Repeal as president of the West Penn Distilling Company, based in New Kensington. During the first year or two after liquor legally returned to Pennsylvania, Stern “made friends” within Pennsylvania’s newly formed Liquor Control Board. Quiet deals with Governor Pinchot’s secretary helped introduce him to the right people and organize the placement of large orders with the new state stores for West Penn’s “Winner” brand blended whiskey.** Even after it was revealed in 1935 that government officials actively helped place Stern’s products in stores, Stern continued to do about $800,000 a year in business with the state for the next 5 years. While only a brief time (1934-35) was spent selling whiskey and gin through the West Penn Distilling Co., David Stern could use his new address in Manor as a new warehouse location for his new products. 18 of his new brands were listed as being produced by one of 2 companies: Fry & Mathias, Inc. or the Monongahela Rye Liquors, Inc.

On July 11, 1940, for the first time, the Pennsylvania Liquor Control Board placed a permanent ban on products manufactured by a Pennsylvania firm. Anything produced by of either of D. Stern’s companies was pulled from the state stores. The liquor board declared that their routine laboratory tests revealed the companies had been “grossly negligent” and “careless in manufacture.” The 18 brands produced by either company that were being served in taprooms across the state were ordered to be disposed of. The state, however, had yet to decide what to do with the 11,000 cases of product they had sitting in their own warehouses or the $30,000 of income that had yet to be credited to Stern’s companies. Some of those brands included Fry’s 4X, General Forbes, Old Bridgeport, Old Manor, Old Westmoreland, White Eagle Rye, Mon Valley Gin, Mon Valley Sloe Gin and Mon Valley Rock & Rye. The problem, it was found, was that fill levels on all the bottles were an ounce shy. When the products were pulled from the market, Stern’s creditors got worried and petitioned Federal Courts to make an inquiry into his company’s finances. Upon hearing this, Stern and all officers of his companies immediately resigned. There were several job dismissals within the state store system, but excuses for the firings were not made public. Governor James admitted to the firings being linked to the Stern case. Ironically, the issue of bottles being an ounce short, or what newspapers described as Stern “getting caught with his pints down” was able to be explained by an expert*** and could have been handled in-state, but the investigation that followed by the federal government put Stern’s business affairs under real scrutiny…and into real trouble.

The federal investigation revealed that David H. Stern had been falsifying warehouse receipts. A conservative estimate of over $500,000 was believed to have been involved in the “deliberate fraud.” Witnesses were subpoenaed to testify in court and explain details about Stern’s business practices. David Stern, however, went missing, and Federal agents were sent to locate him. Stern had a subpoena issued for his presence at his companies’ bankruptcy hearing, but there was no warrant out for him. Testimonies from his ex-secretary and ex-business manager, both of whom had notably been on the payroll of the West Penn Distilling Co., revealed that liquor orders had been manipulated and multiple warehouse receipts were issued for the same barrels to withdraw money from several different banks. Warehouse receipts were viewed by banks as reliable collateral and basically equivalent to cash, so Stern was practically printing money by falsifying and replicating documents. Stern’s business manager, Harry A. Stein, explained how he altered the invoices for the PA liquor board; Stern would meet Stein alone in New Kensington and “dictate a list of additional purchases.” Stein would then “take the original order, sit down at his typewriter and simply add the list which Stern had furnished him, and add it all up to a new and enlarged grand total.” Stein went on to explain that his title was “president” at West Penn Distilling Co., but he “didn’t have any duties” and that the title was “just as much a dummy designation as the title he held of manager at Monongahela Rye and Fry & Mathias.” One of the examples of the falsified orders described by Stein was a liquor order for $445. D. Stern instructed H. Stein to raise the order to $7,925 after explaining that the liquor board had telephoned to increase their order. In a separate testimony, Samuel Leff, a $10,000 investor in Stern’s company (and owner of the Meadville Distilling Co.), gave Stern 1,100 barrels of whiskey to be stored without storage fees in exchange for Stern’s purchase of the certificates once the liquor matured. Some of the whiskey had been used for bottling without Leff’s permission, but Stern paid Leff at least $20,000 to make good on the mistake. All the irregular accounting in Stern’s ledgers put his business accounts in disarray and a federally employed trustee was put in place to organize the chaos.

By the second week of October 1940, David Stern reappeared in Pittsburgh after being found in Arizona. He explained he was traveling to receive medical treatment and had made no effort to disguise his whereabouts. Stern was arrested on October 15th by postal inspectors (due his fraudulent warehouse receipts being sent by mail) and quickly released on $7500 bail. In his November 7th hearing, Stern was accused of issuing warehouse receipts as security for loans and as collateral for bank withdrawals on whiskey that was not on hand or in his warehouse. The banks that credited the loans demanded the right to repossess the whiskey that they held notes for, but many of the creditors held receipts for the same barrels. The judge determined that the bank holding the original copy of all warehouse receipts was the actual owner. David Stern, Harry Stein, and several others, were indicted for mail fraud. Stern pled guilty and was sentenced to serve two years in Federal prison. Fry & Mathias, Inc. and Monongahela Rye Liquors, Inc. were bankrupt. Frye & Mathias distillery property was authorized by the court to be returned to John T. Butler by the trustee. The 11,000 cases of whisky being held by PA liquor board were, presumably, resold and rebottled to recoup some of the losses sustained.

By 1943, Stern had not seen a day of jailtime. Every one of the creditors, Stern’s lawyer explained to the U.S. attorney office, thought it “to their best interests” to suspend his sentence. They understood that Stern “was broke” and they were satisfied with Stern’s last few years of effort to salvage scrap for the war effort. No explanation was given as to how he got the money to enter the scrap business to begin with. The Fry & Mathias Distillery’s interior was completely scrapped and only the shells of a few of the brick buildings remain. The “Fry & Mathias Distillery Sales Company” which was incorporated in February 1939 is still registered in Pennsylvania as an active company. (Fry & Mathias, Inc.’s company type/status is County Orphan.) A century of distilling tradition and history are now a memory with only a few brick buildings left behind to serve as clues of its existence.

*It is likely that the distillery purchased by D.Fry was previously owned by a member of the Painter family who owned grist mills in Manor. George Painter owned a grist mill on Race Street in the center of town. Race Street, which later became Main Street, was named after the race that fed water to one of his two mills.

**There was an inquiry into the Internal Affairs and treasury departments in Pennsylvania’s State Government over the preferential awarding of licenses and liquor contracts with the state stores. Robert S. Gawthrop, who had been a Superior Court Judge, was chairman of the board in 1935, and was interviewed by a House Committee in February 1935. He emphasized his belief that the board should have interventions and be regularly purged of “political inclinations.” He rattled off so many names of politicians, public officials and well-known people that the audience for the hearing “laughed uproariously.” Gawthrop revealed during his testimony that the secretary-elect of Internal Affairs, Thomas A. Logue, and state treasurer, Charles A. Waters, came into his office to ask that the board give another order for Winner Whiskey to the West Penn Distilling Co. so that the company might have more distribution in central Pennsylvania and not just in Philadelphia and Pittsburgh. Gawthrop suggested that Logue was acting “on behalf of a client.” While West Penn Distilling Co. advertised quite a lot in 1934 and 1935, “Winner Whiskey” does not appear in print advertising after that.

***The loss of whiskey in the bottles was explained by Louis Weis, a former rectifier, in his testimony during the hearing. He stated, “It could occur when we bottled the liquor. We used distilled water in blending the brands. We had storage capacity for only 700 gallons.” When asked how much they used at one time he answered, “On some occasions it was necessary to use between 1800 and 2000 gallons. That meant we had to wait until it accumulated in the stills. When we mixed it with the whisky, it was hot.” He was asked what that would cause. “Well, is whisky is bottled at 90 degrees it will contract when chilled to 60 degrees and lose about a half an ounce.”