“There were 6 distilleries licensed to manufacture medicinal whiskey during Prohibition.” If we’ve read it once, we’ve read it a thousand times.

However, this statement is not true for a number of reasons. Let’s address what makes this statement false.

Speaking of false, here are the distilleries Artificial Intelligence credits with manufacturing medicinal spirits during Prohibition:

- American Medicinal Spirits (AMS): The only company that was formed after Prohibition. AMS later became National Distillers, which is now part of Beam.

- Schenley Distilleries: Headquartered in Cincinnati.

- James Thompson and Brother: Later became Glenmore Distillery, which is now part of Diageo.

- Frankfort Distillery: Included the George T. Stagg distillery, which is now known as Buffalo Trace Distillery. Buffalo Trace is the longest continually-operating distillery in the United States.

- Brown-Forman: The only company that is still in business today. The founding Brown family still runs the company.

- Ph. Stitzel Distillery: The predecessor to Stitzel-Weller, which is now part of Diageo.

I believe this information to be oversimplified and misleading, at best, but as a statement, it is easily proven to be false. Firstly, some of the names above describe distilleries, while others describe companies that owned and operated several distilleries. American Medicinal Spirits, for instance, was not a distillery. It was a large corporation with subsidiaries. The American Medicinal Spirits Company (AMSC) operated several distilleries under their license during Prohibition. The AMSC was NOT formed after Prohibition, by the way, (thank you AI for that odd and random piece of nonsense) and it did not become National Distillers. National Distillers was incorporated in 1924 as the reorganization of the U.S. Food Products Corporation. The American Medicinal Spirits Company was formed in 1927 from the reorganization of the American Spirits Manufacturing Company, which was a subsidiary of the U.S. Food Products Corp. National Distillers had been a major shareholder in the AMSC for years, and AMSC was finally fully absorbed by National Distillers in 1929. It did not become National Distillers! It simply became a big cog in a much bigger machine. Yes, it’s confusing, but suffice it to say that National Distillers was the umbrella company. The AMSC, The Kentucky Distilleries and Warehouse Company, and all the distilleries that fell under their management were the property of National Distillers. Secondly, The Thompson Distillery, better known as the Glenmore Distillery, was also one of the companies that fell under the control of the Kentucky Distilleries and Warehouse Company, so it seems odd for them to be on the list and not to have simply fallen under National Distillers. The first barrels of whiskey to be filled in Louisville in 1929 were distilled at R.E.Wathen’s Bernheim Distillery (more specifically, the first barrels filled were labeled as Old McBrayer whiskey). Henry (Harry) E. Wilken was also operating the Elk Run Distillery. Both Bernheim and Elk Run were properties belonging to National Distillers, and neither of them are mentioned on the list. Yet somehow, Glenmore IS mentioned. If we are to assume that they counted as properties of National Distillers, why then is Glenmore singled out? Thirdly, there’s another odd listing for Frankfort Distillery which is meant to cover George T. Stagg, but Frankfort Distillery was owned by Paul Jones Company and Stagg was owned by Schenley toward the end of Prohibition when licenses were issued to those distilleries! You can start to see what I’m getting at about how odd and confusing this list is.

The “6 distilleries” statement is also heavily biased, largely because this commonly repeated statement ONLY focuses on whiskey made in Kentucky during Prohibition. During Prohibition, more specifically between January 1920 and December 1933, medicinal whiskey was also being manufactured in Pennsylvania and Maryland. Medicinal BRANDY, however, was being made in many other locations across the United States. Brandy and neutral grain spirits used for medicinal purposes and in the manufacture of medicines during Prohibition are often ignored, as well. But even when we set aside brandy and neutral spirits, and focus only on whiskey, we must confront the fact that Large Distillery in Large, PA and Gwynnbrook Distillery near Owings Mills, Maryland are excluded entirely. Both Large in and Gwynnbrook Distilleries were manufacturing rye whiskey between 1919 and 1921 before the Willis-Campbell Act shut down their still houses, but they most definitely distilled during Prohibition! Even Pennsylvania’s Broad Ford Distillery manufactured medicinal whiskey after 1930, and any insinuation that they would fall under the list of distilleries belonging to National Distillers is inaccurate. Broad Ford Distillery was not owned by National Distillers until 1933 but was manufacturing medicinal rye whiskey during Prohibition under the ownership of Park & Tilford. Neither Broad Ford nor Park & Tilford appear on that list of 6.

Perhaps one of the most telling lists of distilleries that functioned during Prohibition is the list that was provided by Howard T. Jones during his interview by the Committee on Finance in 1935 before the US Senate. (Read the actual document.) He explained that there were not 7 distilleries, but said, “it was something like 26 or 28.” He provided a list of the following distilleries for the Senators to review:

- The Frankfort Distillery, Inc., no. 17, Louisville, Ky.

- The Old Taylor Distillery Co., no. 19, Louisville , Ky.

- H. S. Barton, no. 24, Owensboro, Ky.

- The Old Quaker Co., no. 113, Frankfort, Ky.

- The Mount Vernon Distillery Co. , no. 27, Baltimore, Md.

- S. Finch & Co. , no. 4, Schenley, Pa.

- Penn-Maryland Corporation, no. 1 , Peoria, Ill

- Ph. Stitzel, Inc. , no. 17, Louisville, Ky.

- Overholt & Co. , no. 3, Broad Ford, Pa.

- The Old Crow Distillery Co. , no. 19, Louisville, Ky.

- The American Distilling Co., no. 2, Pekin, Ill.

- Continental Distilling Corporation, no. 1 , Philadelphia, Pa.

- The Hermitage Distilling Co., no . 19, Louisville, Ky.

- Bernheim Distilling Co., no. 1 , Louisville, Ky.

- Carthage Distilling Corporation, no. 1 , Carthage, Ohio.

- Hiram Walker & Sons, Inc. , no. 3, Peoria, Ill .

- Brown-Forman Distilling Co., no. 414, Louisville, Ky.

- The Green River Distilling Co., no. 27, Baltimore, Md.

- Large Distilling Co., no. 5, Large, Pa.

- Wright & Taylor, Inc., no. 17, Louisville, Ky.

- Black Gold Distillery Co., no. 19, Louisville, Ky.

- Bernheim Distilling Co. , Inc. , no. 2, Louisville, Ky.

- Pennsylvania Distilling Co., no. 6, Logansport, Pa .

- Frankfort Distilleries, Inc. , no . 1 , Baltimore, Md.

- Old Quaker Co., no . 2, Lawrenceburg, Ind.

- Union Distilling Corporation (now Seagram) , no. 1 , Lawrenceburg, Ind.

Gwynnbrook and Glenmore Distilleries are missing from Jones’ list. Gwynnbrook Distillery is listed as being property of National Distillers later in the proceedings, so perhaps it was one of the “ors” Jones described in his list of “26 OR 28”. Glenmore IS on the list, it is just represented as H.S. Barton Distillery, which was the same plant. Jones went on to explain that the 7 distilleries that were understood to be the only companies to have been manufacturing during Prohibition were the original 7 members of the Distillers Institute, each of which contributed $5,000 to its formation. They were:

1. Brown-Forman Distillery Co., Louisville, Ky.

2. Commercial Solvents Corporation, New York, N. Y.

3. Frankfort Distillery, Inc. , Louisville, Ky.¹

4. National Distillers Products Corporation, New York, N. Y.

5. Schenley Products Co. , New York, N. Y.

6. Union Distillery Corporation (now Jas. E. Seagram & Co. ) , New York, N. Y.

7. Hiram Walker & Sons, Inc., Peoria, Ill.

When we eliminate Commercial Solvents Corporation, which was clearly not manufacturing medicinal whiskey, we come quite close to the “usual suspects list” for who was manufacturing during Prohibition! Is it possible that somewhere along the line, this list of the original members of the Distillers Institute were granted the distinction of being the only distillers making medicinal whiskey during Prohibition? To provide some context to why Howard T. Jones might be a trusted source of information- Howard Jones was an attorney for the Distilled Spirits Institute and had access to more information about America’s distillers than most. He had been assistant to Mabel Walker Willebrant while she had been assistant attorney general in charge of prohibition enforcement prosecutions. He had also been assistant to G.A. Youngquist, who succeeded Willibrant, and assistant to Amos W.W. Woodcock after that. He had been in active ccarge of most of the prohibition work done by the Dept. of Justice during Prohibition! As odd as it may be to say, this put him in the perfect position to be hired as a lobbyist for the Distilled Spirits Institute because he knew more about liquor control than anyone! He was not alone, of course. Most of the big shots that worked for the Prohibition enforcement departments went on to become highly paid employees of the liquor industry after Repeal.

To be fair, I have seen many old articles from Kentucky newspapers that state that there were 6 active distilleries manufacturing whiskey during Prohibition…IN KENTUCKY. If your only focus is Kentucky bourbon, it’s understandable that the only distilleries that concern you are bourbon distilleries. But bourbon is NOT the only American whiskey, folks.

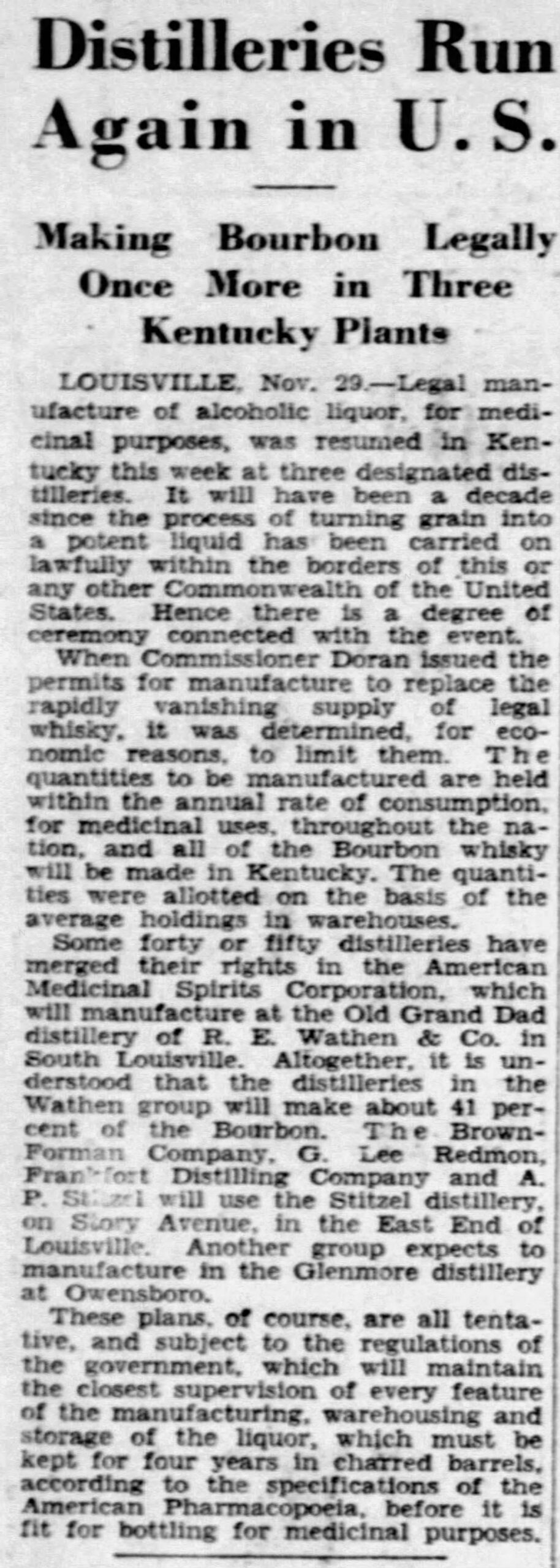

Between 1927 and 1929, the US Treasury Department decided who would be responsible for shoring up America’s dwindling medicinal whiskey stocks. That decision was made with the advice and encouragement of the men that- *surprise, surprise*- ended up with the licenses to carry out the task. But it wasn’t just the 6 distilleries we usually hear about. Dr. Doran, who had been acting Commissioner of Prohibition since 1927, announced in June 1929 that 1,300,000 gallons of bourbon and 700,000 gallons of rye would be produced by 6 companies. That’s right! About 1/3 of the medicinal whiskey allotment was rye whiskey! Obviously, this would not have been carried out by any of the 6 distilleries usually listed. Those 6 distilleries, as described by Doran, were not the final count of active distilleries, by the way! The number would grow when the permits were actually distributed later that year. Of course, not everyone would distill right away, and not every distillery would operate every year before Repeal (1929, 1930, 1931, 1932, and 1933). Schedules and operations shifted every year. The lion’s share of the burden of manufacturing bourbon was assigned to the American Medicinal Spirits Company- again, this was a subsidiary of National Distillers, and again, not a surprise. Lewis Rosenstiel had secured his license to manufacture medicinal rye whiskey at his plant in Schenley, Pennsylvania, and, because he was able to purchase the George T. Stagg Distillery in Frankfort, Kentucky, in 1927, that facility would provide him with bourbon.

The allotments for 1,397,800 gallons of medicinal bourbon were assigned as follows:

- American Medicinal Spirits Company, 859,600 gallons

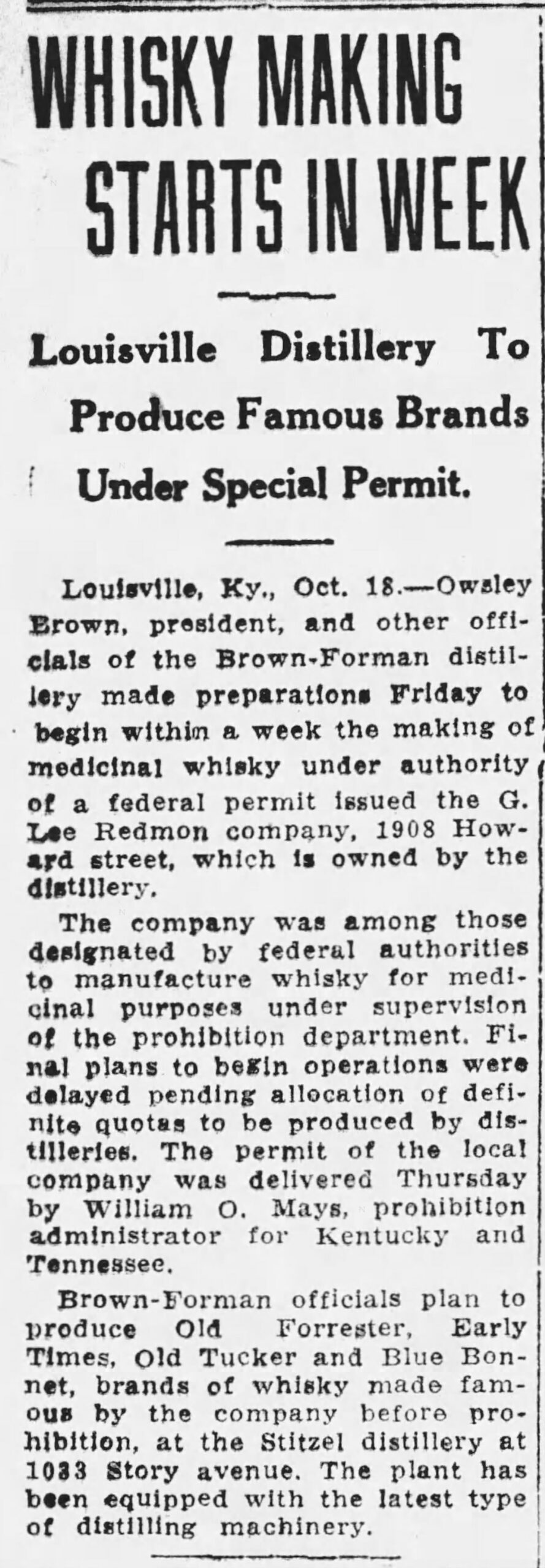

- Brown-Forman Distilling Company, 105,000

- Pepper Distilling Company, 37,000

- Frankfort Distilling Company, 203,200

- Stitzel Distilling Company, 65,000

- Glenmore Distilling Company, 128,000

What does it mean, then, that Brown Forman used Stitzel Distillery’s stillhouse to manufacture their whiskey in 1929? Perhaps the lines dividing the companies were somewhat blurred if they were working so closely together. Joseph Wolf, owner of the Pepper Distilling Company lived in Chicago, but spent a great deal of time in Kentucky. He was “lucky” to have a direct connection the Commissioner of the City of Lexington through his plant manager, Wood G. Dunlap (elected to serve in 1918), so he was able to procure a license to establish a concentration warehouse several years later. Dunlap remained in Wolf’s employ, and in 1927, he was instructed to ready the Pepper Distillery for its inevitable future use producing medicinal whiskey. Needless to say, the men that were assigned licenses to manufacture America’s whiskeys in 1929 were allowed many unfair advantages. Whether these distillery owners knew one another or not is immaterial (They did). The fact is that these men were thrust into one another’s business environment. They met behind closed doors with powerful men in government and authored their own destinies. But they don’t get to keep writing their own history 100 years later. There were other distilleries and other owners that ALSO had unfair advantages and moved the needle for American whiskey history.

Even if this information has not moved you to consider the possibility that the statement “There were 6 distilleries manufacturing medicinal whiskey during Prohibition” is false, perhaps you could consider the idea that the statement is not entirely accurate? Perhaps we could stop trying to turn American history after Prohibition into easy sound bites and admit that more research is required. I’ve spoken to many well-respected whiskey historians that have freely admitted that their research was strictly focused on bourbon, so these incongruent pieces of information were not part of their research. But they exist and they should be considered. If only to spark debate. What do you think?