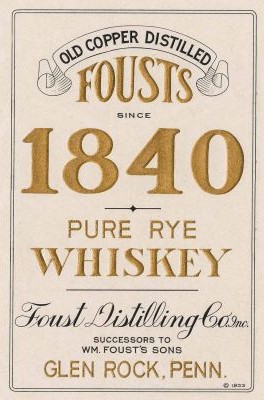

The Fousts, a distilling family that had been making whiskey in York County, Pennsylvania since 1840, marketed their products in incredibly unique containers. William Foust had always used creative glass flasks designed in interesting shapes; horns of plenty, shells, guns, billy clubs, vegetables, etc. They even applied for patents on designs in full color ceramic. It is difficult to date the containers, but we can guess approximate dates based upon the circumstances surrounding the whiskey industry at the time.

The Fousts, a distilling family that had been making whiskey in York County, Pennsylvania since 1840, marketed their products in incredibly unique containers. William Foust had always used creative glass flasks designed in interesting shapes; horns of plenty, shells, guns, billy clubs, vegetables, etc. They even applied for patents on designs in full color ceramic. It is difficult to date the containers, but we can guess approximate dates based upon the circumstances surrounding the whiskey industry at the time.

Glass containers were too expensive to be used by the whiskey industry to market their products until advancements were made in bottling. The 1890s saw a remarkable increase in glass manufacturing. It is likely that W. Foust’s flasks were a creative marketing development born from the drop in manufacturing costs. Foust would have been very familiar with Pennsylvania’s booming glass industry. 50 glasshouses sprang up in Pennsylvania between 1763 and 1850, with at least 40 of these situated in Pittsburgh. 14 of these Pittsburgh glass houses produced flint glass, a type of clear crystal, the other 26 making strictly utilitarian items such as windowpanes and cider, beer, and whiskey bottles.

Pennsylvania, especially Pittsburgh, had the advantage of proximity to cheap fuel (coal) and access to a good waterways system, which afforded an inexpensive means of distribution. By 1875 the Rochester Tumbler Company of Rochester, Pa. boasted it could make 500,000 pieces of glass a week. Pennsylvania’s oil industry, which was growing exponentially in the 1880s, increased the amount of natural gas available. Natural gas, a biproduct of the oil industry, allowed furnaces to more easily reach high temperatures, and literally fueled the expansion of glass manufacturing in the Allegheny region. Probably the most notable advance in glass production took place between 1895–1917 with the invention and patent of an automatic bottle blowing machine by Ohio engineer, Michael Owens. By 1902, there were over 150 glass factories in western Pennsylvania, eastern Ohio, and the northern panhandle of West Virginia. By 1920, this area produced 80% of the nation’s glass.

As all these advancements were taking place in glass production, the whiskey industry was undergoing change as well. Industrial manufacturing plants were making more whiskey than could be consumed in the mid-1890s, resulting in overproduction and causing a loss in its market value. Distillers even had to go as far as collectively agreeing to stop making whiskey altogether from 1896-1897 to help reduce the “whiskey glut.” This familiar trend in industrial overproduction has happened in more recent times, and one of the responses from the whiskey industry was to produce specialty containers to draw customers toward a particular product. The collector’s edition decanter may have, in fact, been a much earlier invention of Pennsylvania distillers. William Foust was arguably the most creative in this group.

When one considers why Foust created these specialty flasks in the first place, the answer may be that he was using his marketing savvy to create a niche market for his whiskeys during this era of overproduction. If that is the case, it makes sense that he would have taken advantage of the glass manufacturing boom while marketing his products to the public at the same time. When the ownership transition began to take place at the Foust Distillery between father and sons, the decanters began to transition from glass to full color ceramic decanters. Some designs were inspired by earlier glass flasks, while others were new and original. The salted pretzel ceramic flask, for example, had its patent applied for in 1908. Just as the collectible decanters that were made in the mid to late 20th century have become collectors’ items, the flasks that resulted from Foust’s creative marketing strategy have become even more desirable (and quite expensive) today.

When one considers why Foust created these specialty flasks in the first place, the answer may be that he was using his marketing savvy to create a niche market for his whiskeys during this era of overproduction. If that is the case, it makes sense that he would have taken advantage of the glass manufacturing boom while marketing his products to the public at the same time. When the ownership transition began to take place at the Foust Distillery between father and sons, the decanters began to transition from glass to full color ceramic decanters. Some designs were inspired by earlier glass flasks, while others were new and original. The salted pretzel ceramic flask, for example, had its patent applied for in 1908. Just as the collectible decanters that were made in the mid to late 20th century have become collectors’ items, the flasks that resulted from Foust’s creative marketing strategy have become even more desirable (and quite expensive) today.