The last few weeks have been spent trying to find my way back onto social media platforms. I was kicked out on October 1st when I crossed our northern international border into Canada and haven’t been able to get online since. It’s been three weeks now and I am itching to write about all the things I’ve been reading and learning about. Canada may be considered the quietly dignified and unassuming northern neighbor to the United States, but its whiskeys also share that same reputation. It’s amazing how little we talk about them and how much they’ve altered our American palates! Canadian whiskies have been incredibly influential to our domestic whiskey industry since the 1920s, but no one seems to recognize the sea change that occurred. I was captivated by Canada’s whiskey industry during my week visit (Oct 1-6th) and every bit of information I absorbed left me wanting to know more.

I’ve followed Davin de Kergommeaux’s writing about his beloved Canadian whisky over the years and listened to his interviews, but the information, it seems, never really sunk in. For me, it was always “off-brand” from the history of the American whiskeys I love so much. That and the possibility that “Canadian rye” might be confused with Pennsylvania’s rye whiskey making traditions- that has always been a bit blasphemous to me…But that’ll teach me to be dismissive! There’s always more to learn! And in the world of whiskey history, we’re all guilty of not seeing the big picture beyond the kinds of whiskeys we love to research. My love for Pennsylvania rye has certainly made me a bit too tunneled visioned, but I shall try to be less so. As I’ve been revisiting articles written about Canadian whisky and relistening to the interviews with Mr. de Kergommeaux, I have been forcing myself to be more open-minded. (The many comments about Americans being too close minded about whiskey-making certainly hit home!)

What never occurred to me was just how much Canadian whisky has influenced the American whiskey industry. The fate of Canadian whisky was dictated by the temperance movement and Prohibition (their own and ours). I read an article recently where the author echoed de Kergommeaux’s belief that Canadian whiskies were superior to other whiskey styles because of the freedom Canadian blenders have in crafting their spirits. The article explained, “Instead of mashing all the grains together, Canadian distillers mash, ferment, distill, and age each type of grain separately. Then those finished whiskies are combined. That gives the blender an incredible amount of freedom—each individual grain can get individual attention.” While I agree that there is a great deal of freedom in both being able to add as much as 9.09% of other spirits into the blend and being able to pick and choose which flavor components will go into your whiskey, I have to push back a bit on the idea that this method might be “better.” Different and interesting, yes. But this blending of spirits is an entirely different art. This is the art of rectification. Americans have been cut off from their long history with its own rectification traditions connected to whiskey-making, but it seems Canada never lost theirs. And that deserves some more admiration.

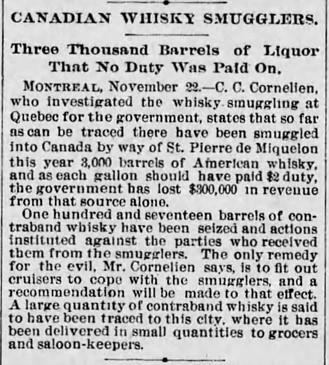

America, before Prohibition, boasted thousands of liquor firms across the country, each with their own rectifying license. They were the nation’s bottlers of whiskey. Today, we take our three-tier distribution system for granted- the producer makes and bottles the alcohol, sells it to distributors, and the distributors deliver and sell the alcohol to retailers (i.e. bars, restaurants, liquor stores), and the consumer buys it from the retailer. But before Prohibition, distillery companies spent many decades (some spent generations) building their own distribution networks. Smaller, more boutique distilleries maintained their own businesses by selling locally and by doing business with trusted liquor firms that bought their products in bulk. Distilleries shipped their products wholesale around the country either to their own warehouses or to liquor firms that bottled for them or blended under their own labels. Many of the liquor firms were generations-old family businesses that had formed trusted relationships with their clients (local hotels, restaurants and other businesses). Larger, vertically integrated distilling companies didn’t just distill and age their products on site- they rectified, bottled, and distributed their own whiskeys from their many satellite locations. So how did all of these thousands of unique, American businesses stay viable among so much competition within the industry? While the large distillery businesses managed to sell their products both nationally and internationally, smaller distillers and liquor firms focused on local markets and never needed to compete in the larger markets to remain viable. What was popular in one city was not necessarily what was popular in another. This relative balance within the industry remained intact until the late 1880s when the Whiskey Trust began to seek a monopoly in liquor sales. The trust was eventually forced to dissolve in the early 1890s, but almost immediately reorganized into a corporation called the American Spirits Manufacturing Company (and its subsidiaries). During the late 1880s and early 1890s, Canadian and American border states were involved in a great deal of whiskey smuggling. Oddly enough, we tend to only associate smuggling with the Prohibition era, but smuggling of products will take place any time there’s a opportunity for big profits. It just so happened that the tariffs on American goods were very high in the late 1800s and Canadians were glad to avoid paying them. Border state newspapers complained about all the illegal whiskey smuggling going on and defended farmers along the border that were having a difficult time dealing with the political climate’s effect on their ability to turn a profit. The costs to bring American goods into Canada were prohibitive for legal trade but created a steady market for an illicit one.

Here lies the beginning of the end for America’s rectifiers. Even if the business of rectifying had been a part of the American whiskey-making industry since its inception, rectifiers were difficult for the Whiskey Trust to control because they acted independently. They were undesirable competition, and that competition was widespread. Rectifiers they were also vulnerable small businesses because they were dependent upon their suppliers. The power dynamic within the industry in the 1890s was shifting toward the newly formed corporations and away from the wholesale liquor associations that had been in control of the industry since the Civil War. The lobbying arm of the newly formed American Spirits Manufacturing Company (Whiskey Trust) was adapting to achieve its new goals. The Trust’s goal of creating a monopoly remained, but this time, its new corporate model would concentrate on controlling/buying the distilling companies with the best distribution networks. By 1899, the American Spirits Manufacturing Company (ASMC) owned most of the straight whiskey distilleries in Kentucky and consolidated them into a subsidiary- the Kentucky Distilleries and Warehouse Company. They sought to control Pennsylvania and Maryland ryes, too, but were unsuccessful. The early 1900s saw the ASMC investing heavily in advertising firms. They advertised against rectifiers and promoted their newly acquired straight bourbon interests. Rectifiers represented the largest competition for the Whiskey Trust- This may seem counterintuitive because we often associate the Whiskey Trust with neutral grain spirits and with rectification, but that was the old Whiskey Trust. This new iteration would have its cake and eat it too! Now in control of most of Kentucky’s straight whiskey stocks, they could promote their bottled in bond whiskeys (That law was conveniently passed in 1897 just after the Whiskey Trust was reformed in 1895) and raise the prices of aged whiskeys while profiting from their own Peoria-produced rectified spirits, as well. Quite clever, actually. By literally owning massive stakes on both sides of the argument, they couldn’t lose. And by taking steps to gain control of the bottling industry while taking the bottling power away from the country’s rectifiers, they could cement their hold on distribution.

By the time Prohibition arrived, the American Spirits Manufacturing Company was already setting the stage to dominate the medicinal whiskey market. They negotiated the consolidation of most of America’s whiskey to be placed in their own warehouses so they might act as “steward for America’s whiskey.” They eliminated any competition from other bottlers (rectifiers) and placed the owners of America’s largest bottle manufacturing companies on their board of directors. They negotiated the use of their own distilleries in the production of most of America’s new-make medicinal whiskey during Prohibition. They even helped to eliminate wholesale sales of whiskey “by the barrel” after Prohibition by weakening the coopers’ unions and promoting the use of ONLY bottles to “keep whiskey safe from adulteration.” Conveniently for them, they had access to most of the nation’s bottle manufacturing. The monopoly had been slowly achieved – completely legally with the aid and approval of the US government! The irony in all this manipulation by the Whiskey Trust to achieve its ends in the US whiskey market was that the real winners ended up being…the Canadians!

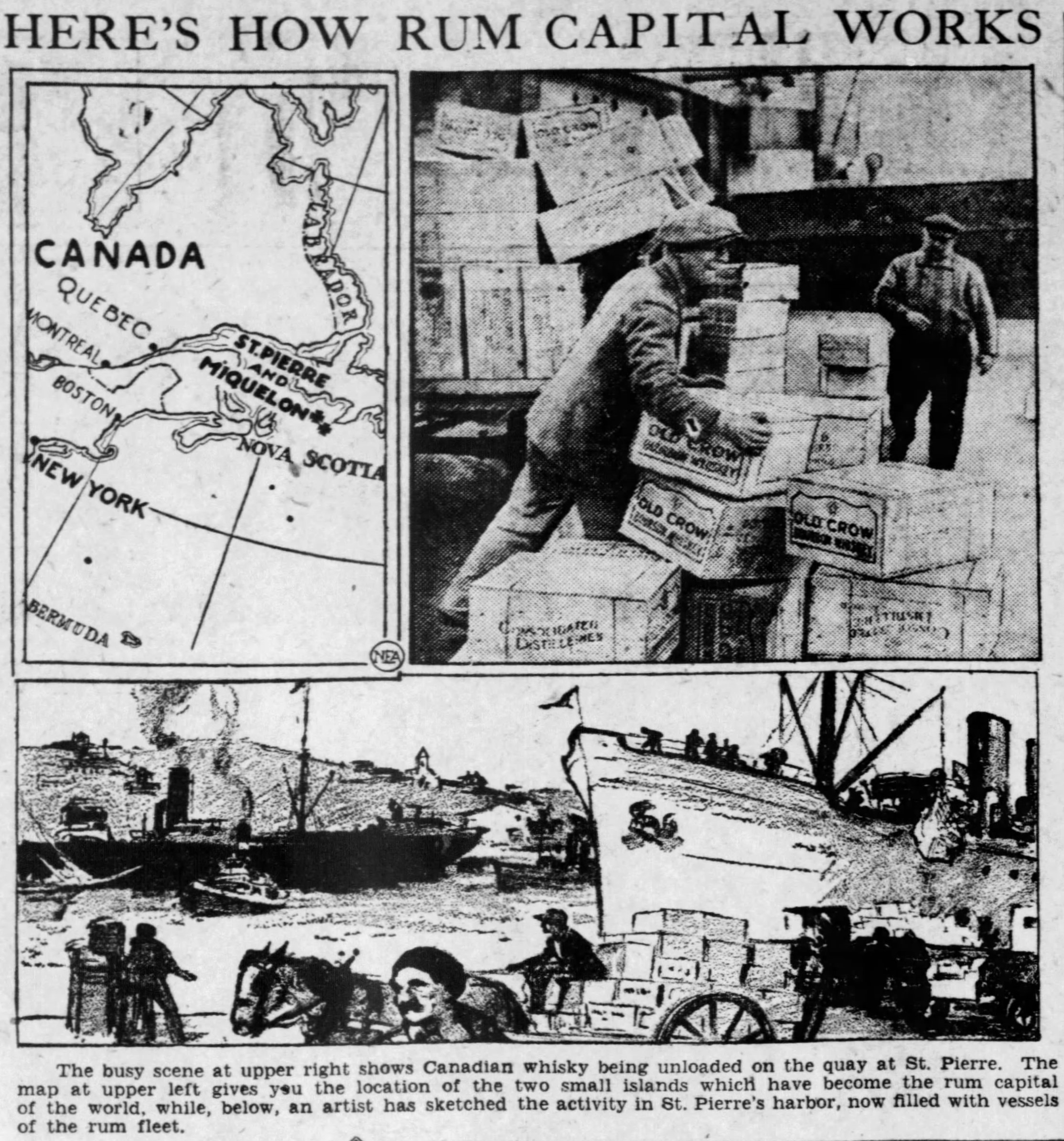

Canada faced down its own temperance movement and a short-lived national Prohibition, but the 1st World War quickly brought any bans on liquor sales to an end. Like Canada, The United States imposed its own restrictions on distilling in 1917 for the war effort, but our government went much further, passing the 18th amendment and instituting a federal prohibition on liquor. Legal sales of Canadian whiskey to the United States as medicinal whiskey continued to take place, but most of the Canadian whiskey being consumed by Americans in the 1920s was bootlegged liquor. The size of Canada’s distilleries grew exponentially between 1920 and 1933 as they attempted to meet demand, but America’s insatiable desire for whiskey could not be met. American gangsters like Al Capone made fortunes by smuggling Canadian whiskey across international borders. The floodgates had opened, and there was little that America’s liquor interests could do to stop from drowning. In May 1923, the Philadelphia Inquirer published an article headline that read, “Enforcement Agents Frankly Assert Inability to Curb Traffic Which is Making Millionaires Daily and Floats Entire Middle West With Wet Goods to be Resold at Fabulous Prices.” The article explains how thousands of smugglers were moving more than 100,000 gallons of illicit whiskey into Michigan daily. In 1929, US border agents claimed to have seized 16,594 cases of smuggled Canadian whiskey, but admitted that “that did not constitute one-tenth of the total amount smuggled in.” The boat traffic leaving Canada loaded with liquor was known to be headed to the United States, but they were not stopped because their manifests listed that the goods were headed for Europe and there was no reason to stop trade with Europe. Eastern cities were awash in Canadian whiskey throughout the 1920s!

Before Prohibition, there was little doubt that American rye whiskey and bourbon were superior products in the eyes of American consumers, but beggars can’t be choosers when liquor is illegal. Canadian brands became so popular that an illicit trade in forged labels sprung up and most of the Canadian whiskey that was being sold illegally in America’s large cities was counterfeit. Big surprise, right? Well, all this illicit liquor traffic was affecting the expectations of American’s palates and lowering the bar for what Americans were drinking. No offense to Canadian whisky, but it has always been a much lighter spirit from what Americans were drinking. Illegal whiskey or not, the American whiskey industry was upended by our unlikely northern neighbors.

By the time Repeal came around, the largest supplies of America’s whiskey stocks were in the hands of National Distillers (aka American Medicinal Spirits Company) and Schenley. Hiram Walker Gooderham & Worts Co. and Seagrams were supplying a much more inexpensive, bottled-in-bond, aged product while National Distillers and Schenley were blending their aged stocks with neutral grain spirits. They were cutting aged bourbon stocks as much as 1 to 5 and old rye whiskey as much as 1 to 7! The uncut aged whiskeys were being sold were going for 7 or 8 dollars a pint while blended whiskeys were closer to 2 or 3 dollars. The idea that average American whiskey drinkers would be willing to pay 4 and 5 times the prices they paid for the same whiskey before Prohibition is just not realistic. In Pennsylvania, the newly formed state liquor stores tried to calm the public’s frustration by assuring them that they would undercut the prices being charged for Canadian whiskey and that they would refuse to sell it at all in their stores. Is it any wonder that whiskey drinkers chose to still drink Canadian? These companies were not at the top of the food chain for American drinkers before Prohibition and would not have been large stake holders after Repeal if it hadn’t been for all that illegal trade during the 1920s.

American whiskey history often describes the American palate as moving away from heavier spirits and toward a lighter profile after Prohibition. Is it any wonder? Anyone can see the trend as it took place. But I would argue that American whiskey makers shot themselves in the foot by rushing blended whiskeys to market in the 1930s after Repeal. The Canadian distillers which had grown to massive sizes during Prohibition were happy to continue their trend of supplying Americans with more. I’m not sure our palates changed as much as the depths of our pockets. Americans wanted to drink legally and they wanted the best that they could afford to drink. And that…was no longer 8- and 10-year-old ryes and bourbons. They were a relic of the past. Canadian whiskey was here to stay and the American market bent toward supplying our own version of our northern neighbors’ goods. C’est la vie.