I have been thinking a lot lately about labeling terms for whiskey that we take for granted in the United States. Bottled-in bond, straight whiskey, bourbon, pure rye, fine old rye, etc.- they are usually seen as distinct to the American whiskey industry. I covered the term “bottled-in-bond” and how it was used in the United Kingdom long before it was used in the United States in my last two blog entries, but I want to explore how these other terms came be used within the liquor industry. My interest in the origins of these terms is not meant to undermine the unique nature of American whiskey in any way! This blog post is only meant to explore how they evolved and why they were used in the first place. As it happens, the whiskey industry adopted much of its terminology from words that had already been in use. When the industry adopted them, it kept them and made them their own.

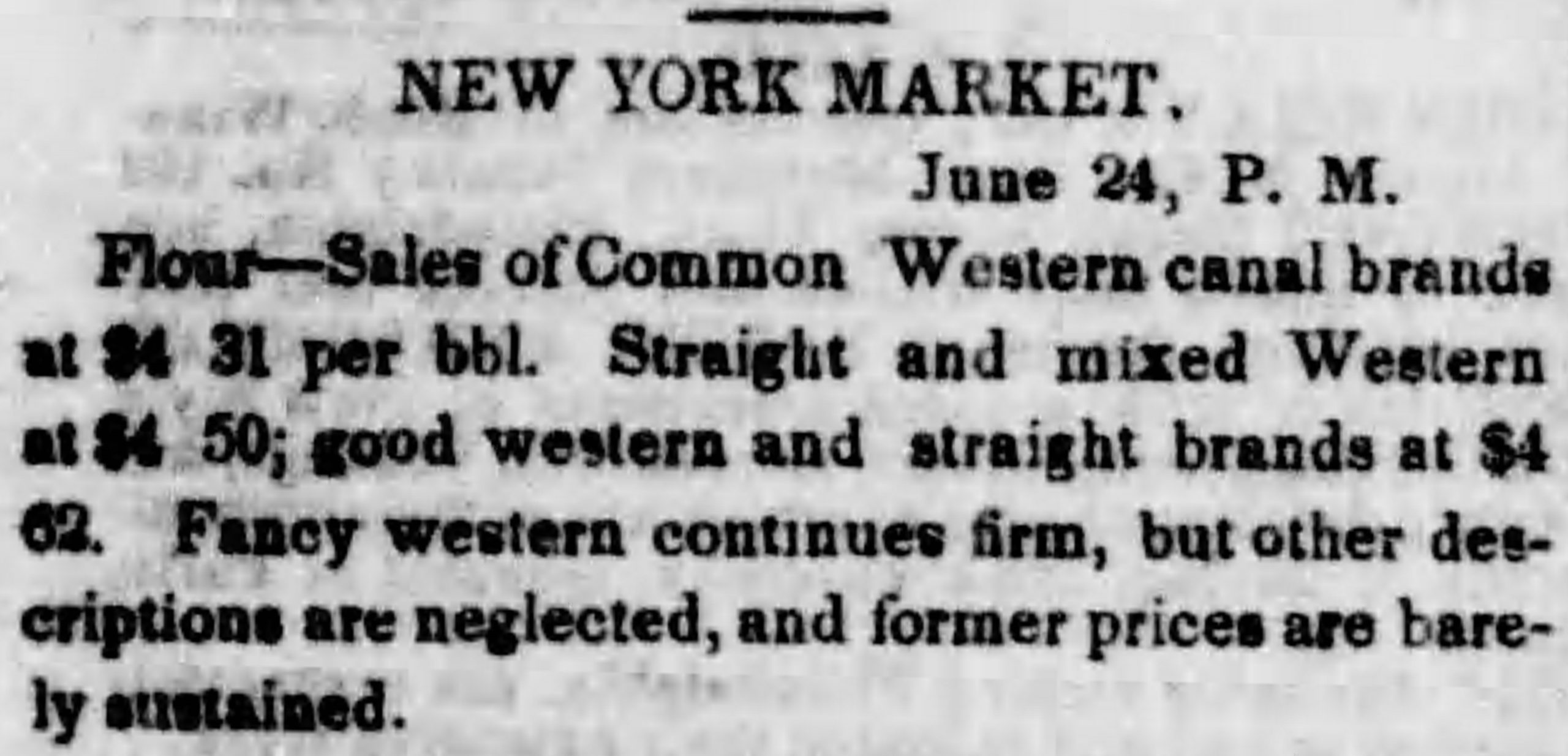

Last March, when I was digging into a theory on the origins of the term “straight,” I sought out the expertise of Justin Cherry, an incredible baker and grain historian from Mount Vernon’s Mill and Distillery in Virginia. I was finding through my research that the earliest use of the term “straight” wasn’t used for whiskey at all. In fact, the earliest use of the term was in the early 1800s when it was used by the flour/milling industry. “Straight flour” was consistently showing up as a commonly used term in commodity market listings and in ship manifests. So- I asked Justin Cherry about the use of “straight” in flour production in the 18th and 19th centuries. He explained that the flour/milling industry was inventing words to describe the quality of bulk commodity flours being produced by all the new roller mills being built in the 1830s and 40s. Roller mills were a new technology that distillers and millers were quickly embracing in the mid-19th century. Steam replaced water power in the milling process, and the entire process became more consistent, less wasteful, and increased output significantly. “Straight flour,” he told me, described the “grinding of flour dust and middlings.” Don’t worry about understanding those milling terms- You don’t need to understand the intricacies of a grist mill or the differences between grinds to see that this term “straight flour” was common within the trade. (The term “straight” is still used to describe flour today, though only within the industry. See more info HERE)

Around 1850, early use of the term “straight” was being applied in the western territories by liquor salesmen and liquor shop owners to describe unrectified, barrel aged whiskeys. Ads were listing straight whiskeys as being whiskeys that were at least a year or older right during the 1840s-1850s. This timeline coincides with the completion of the railroads heading west. The western territories were gaining more immediate access to products produced in the eastern markets. Could it be that salesmen were applying language normally reserved for describing grain quality to whiskey? It seems likely- the term “straight flour” implied quality. Either way, it cannot be denied that the term “straight” is connected to the histories of both flour and whiskey and that its connection to flour is older. Of course, straight whiskey, as we think of it, wasn’t applied with any regularity to bourbon until around the 1870s. Before that, bourbon was simply referred to as “pure bourbon.” Bourbon makers would later embrace the word “straight” while rye makers preferred to use the term “pure rye.” But before we get to “Pure rye” what about bourbon? Where did that term come from?

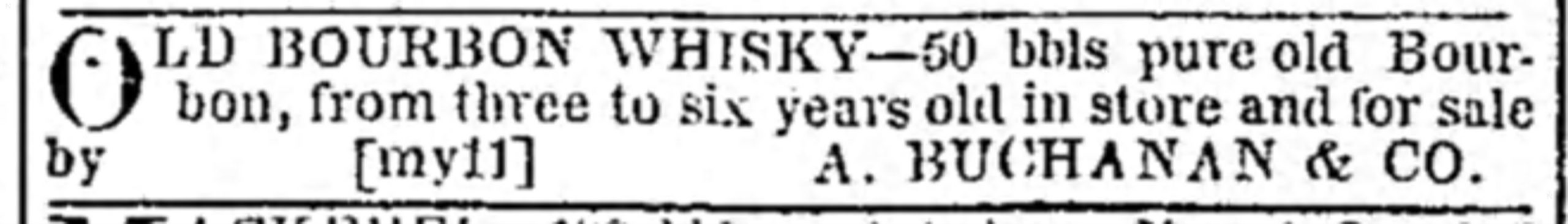

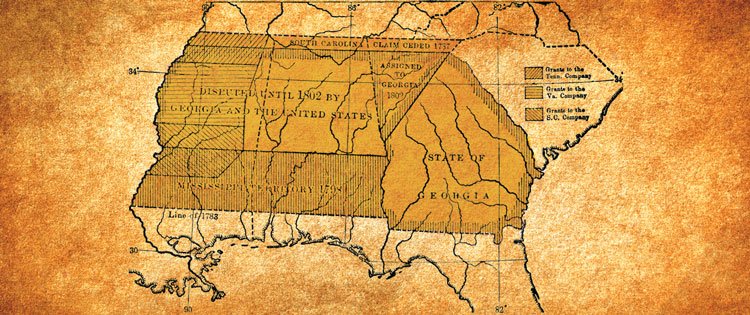

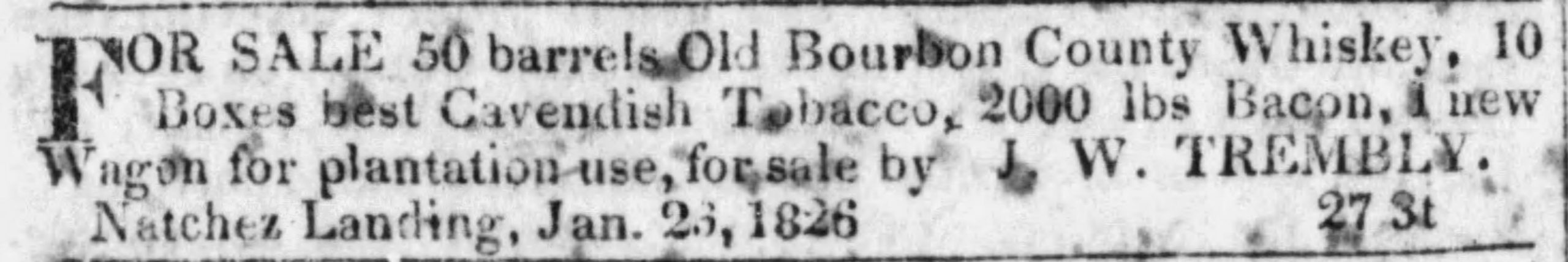

I have seen every explanation for the term “bourbon”, but my reasoning is only based only on the proof that I have seen. Bourbon is not used to describe whiskey until the 1820s. Kentucky sources show the first mention of bourbon whiskey appears in print in 1821. I’ve found articles like the one below showing an affinity and appreciation for locally produced items in Kentucky by its citizens. Bourbon County had been formed in 1786 from Fayette County and was whittled down in size after Kentucky became a state in 1792. The early 1800s brought a lot of attention to the Bourbons due to the Bourbon Restoration taking place in France. Newspaper articles splashed the news of the political changes taking place abroad. “Bourbon” was becoming a recognizable word across the young American nation. There was a famous racing horse named Bourbon and even a popular type of snuff tobacco called Bourbon. Pro-French Jeffersonians would certainly have welcomed a whiskey called “bourbon.” The first governor of Kentucky, who was pro-French, was largely responsible for making a deal with the Spanish to open up reliable trade traffic on the Mississippi River all the way down to New Orleans. To add to all this “bourbon” discussion, the Georgia territory, which extended all the way to the Mississippi River until 1802, had been in dispute as part of the Yazoo-Georgia Land Controversy.

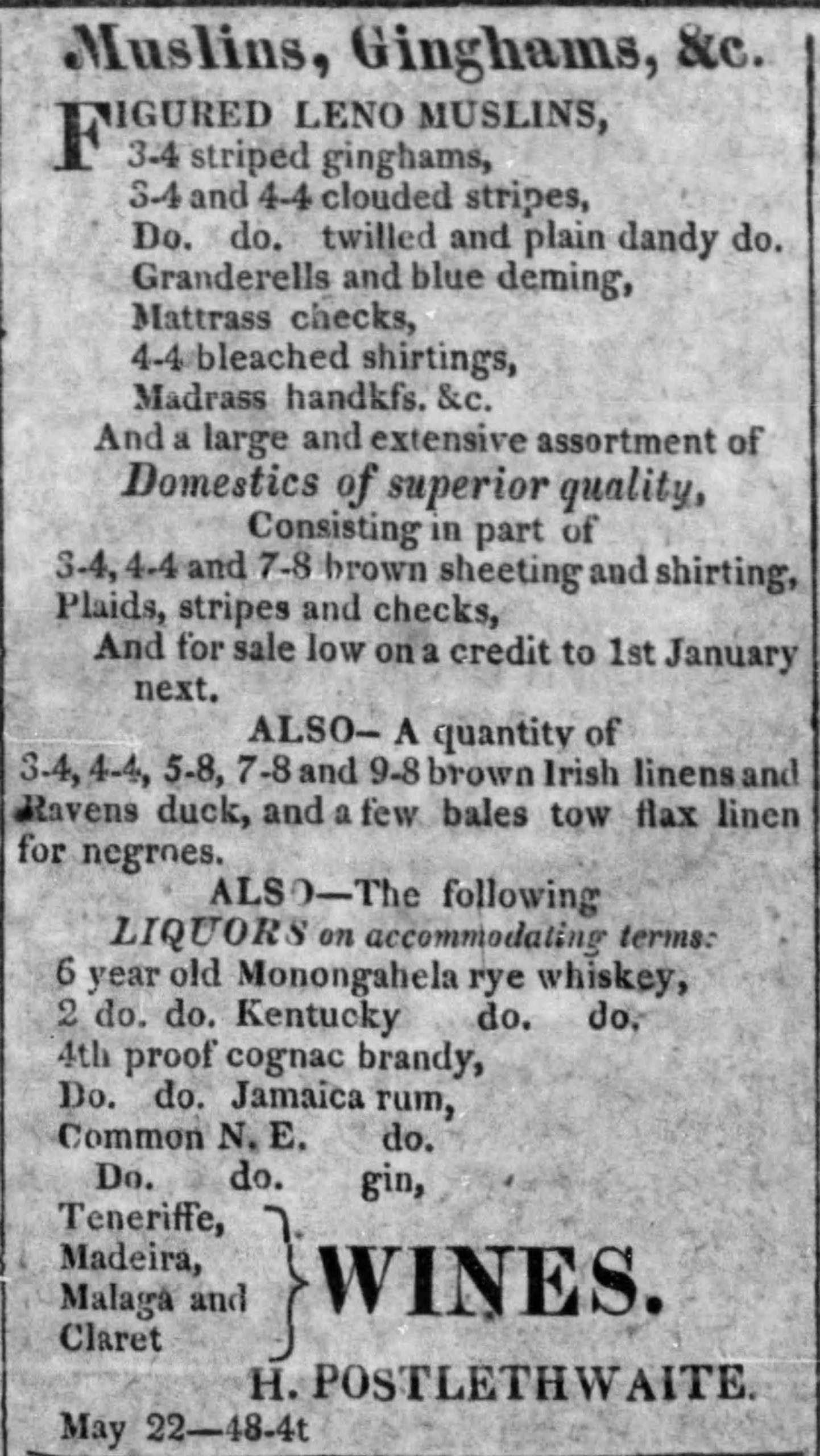

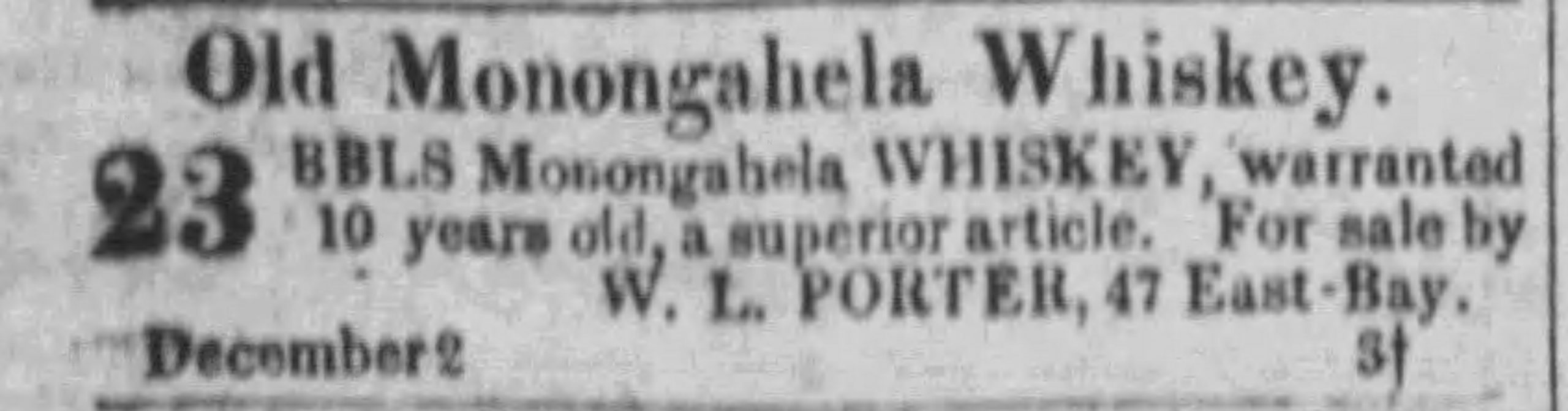

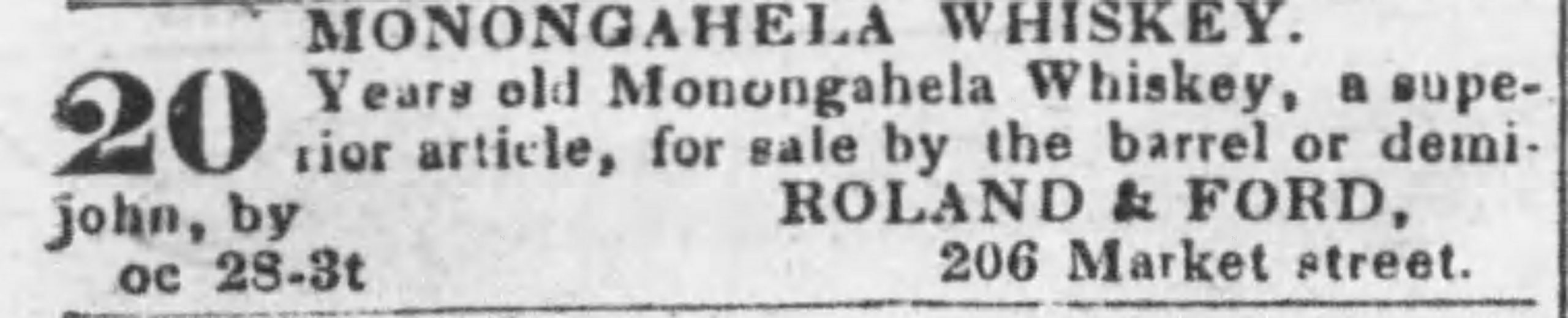

And guess what the name of the Georgia “county” bordering the Mississippi was in 1785? That’s right- Bourbon County! Of course, THIS Bourbon County, though short lived, would have been part of Tennessee and Alabama today. It didn’t stick and the borders of Georgia were pushed east behind the Chattahoochee River, but there’s no doubt that the name stuck in people’s minds. It is believed that Bourbon County, Georgia was named after the Bourbons of France. Go figure. From what I have seen, there is no reason to believe that bourbon didn’t evolve the same way any other name has- from a consumer connection to quality and regional recognition. Bourbon may not have been specifically from Bourbon County, Kentucky but all that mattered was what consumers associated it with. The name “bourbon” would conjure images of old corn whiskey from the south just as Old Monongahela rye would conjure images of old rye from western Pennsylvania. It is likely that Kentucky distillers, just as Pennsylvania distillers had before them, adopted a name for their whiskeys based on the success that the name was having with consumers. It may have started with a handful of men calling their whiskeys “bourbon,” but the trend grew. Bourbon became a universally recognized whiskey style over a half century of building a name for itself. This reality of brand and name recognition remains unchanged today.

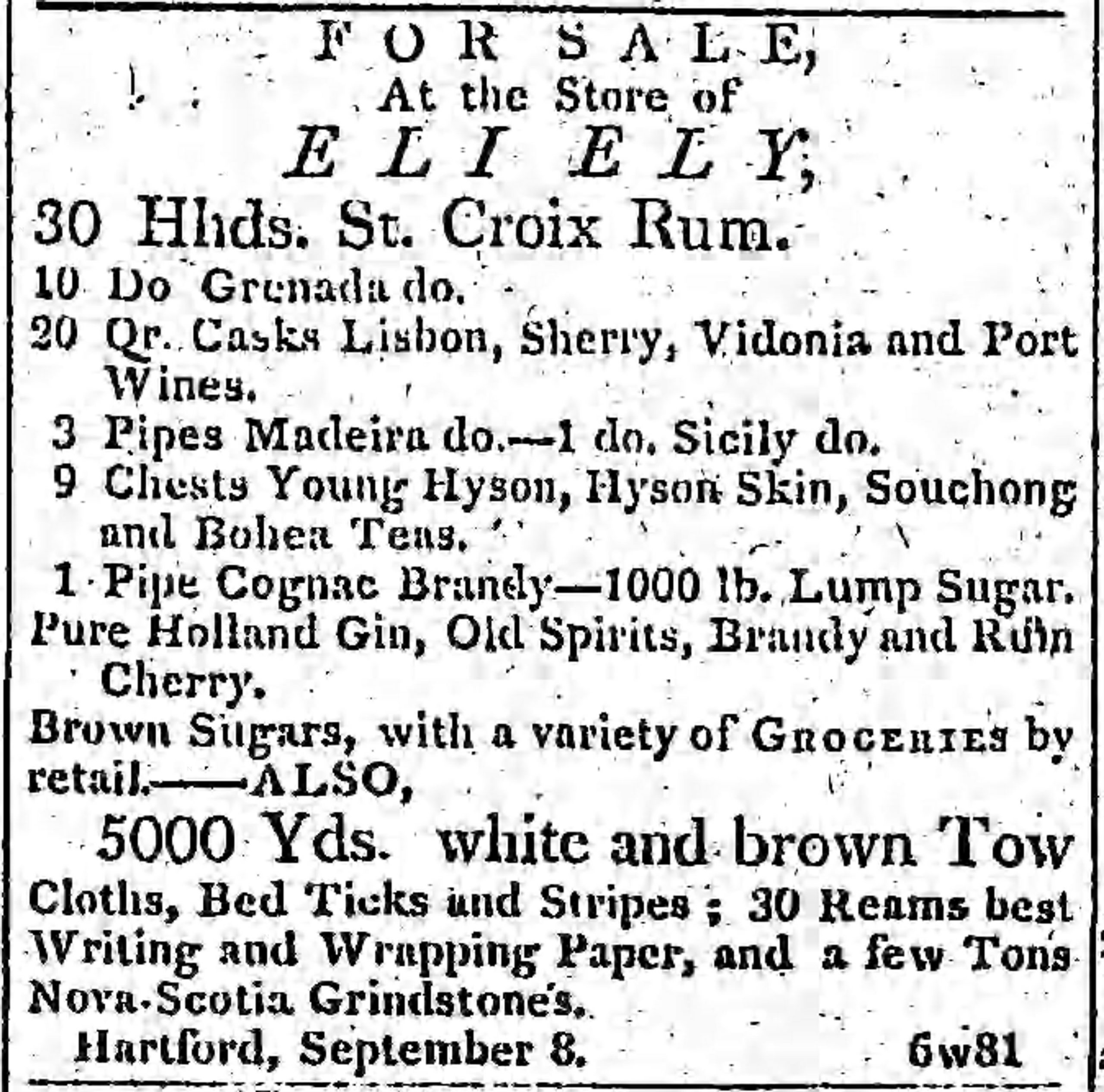

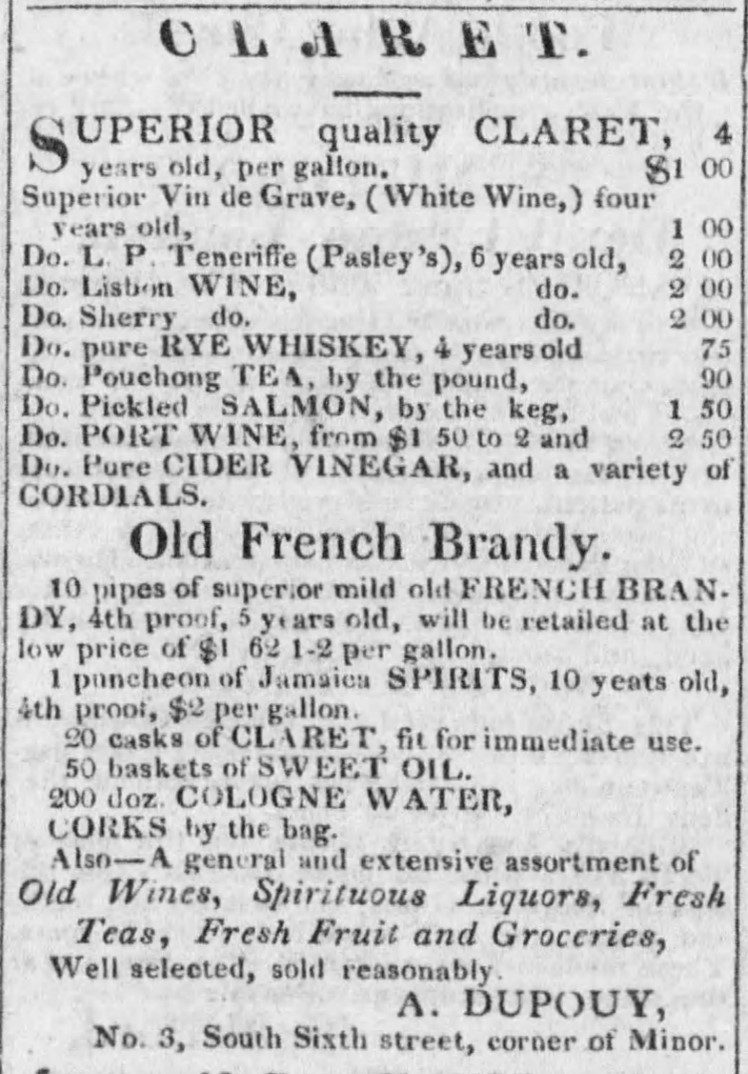

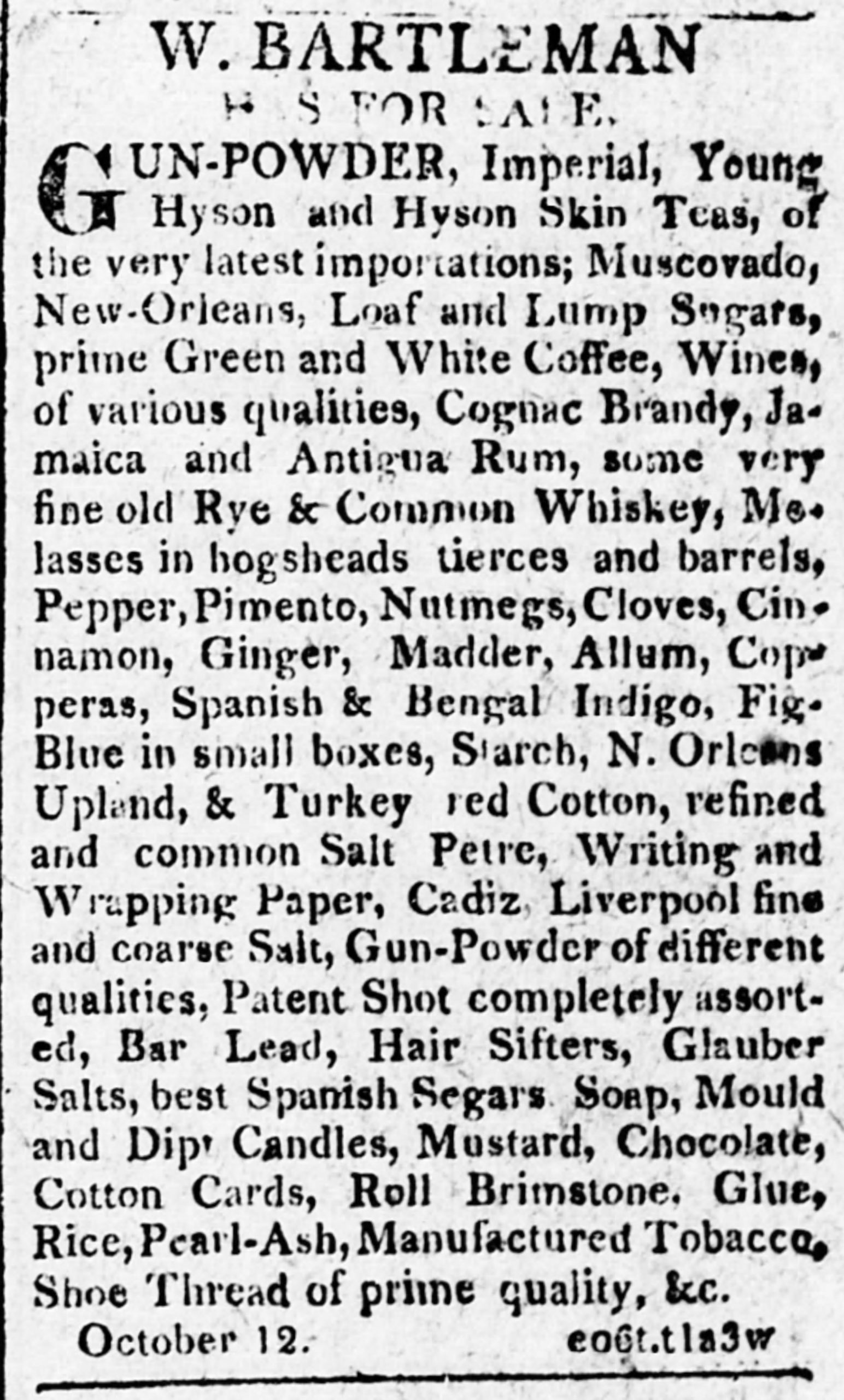

“Pure rye” was not without precursors either. “Pure” was used to describe many other liquors and fortified wines before rye whiskey became a commonly available product in the late 1700s and early 1800s. Rectification was commonplace, so it was necessary to be able to stress to buyers that a product was the pure article and had not been rectified. Spirits like “pure rum” were used medicinally. “Pure Holland gin” was quite popular and were understood to be the best on the market, so it was often reproduced.

It follows that when rye whiskey became available to a larger market that distillers and salespeople would want to stress when their product was unadulterated. “Pure” had been used in the past and would serve to bolster the value of rye whiskeys from Pennsylvania and Maryland. By the early 1800s, “pure rye whiskey” was a common description for barrels of rye whiskeys for sale.

How did “fine old rye” come to be a description for rye whiskey? “Fine” and “fine old” were not exclusive to whiskey advertising- they’ve been used to describe many spirits throughout history. “Fine old madeira,” “old port,” “old French brandy”, etc. were commonly seen among the imported items advertised for sale in newspapers. But I kept finding references to “old” and “fine old” to describe rye going back into the 1700s. Now how could that be when we all have come to believe that “old rye” or “old Monongahela” meant barrel aged rye? Brown spirits weren’t supposed to be around until the early 1800s, right? Either our understanding of when barrel aging became popular is off or the term “old rye” originated elsewhere.

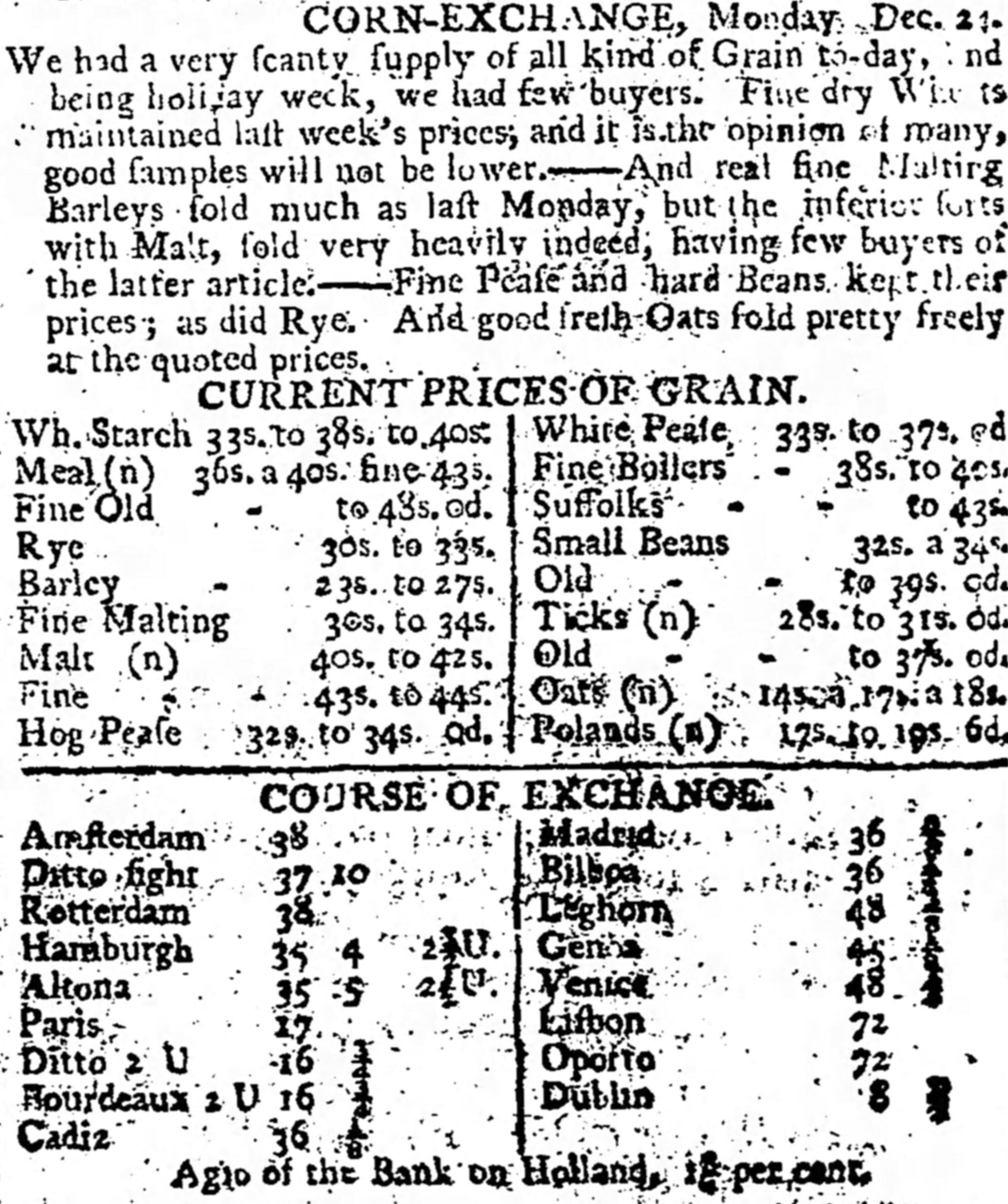

After doing some digging, I found that grain markets and grain merchants advertised the quality of their grain with those same descriptors. “Old barley, old rye, old corn…fine old rye”…they were listed in the newspapers in the late 1700s to describe grain for sale off the ships at ports like Alexandria, Va. or Newport, Conn. or in London or Philadelphia. It makes perfect sense for whiskey to have been distilled from different grades of grain. It also makes perfect sense that the grain quality would speak to the quality of whiskey as well.

When I began looking at “old rye” and “fine old rye” the same thing happened. “Old rye” was used to describe grain. But this time, instead of flour, it was describing seed. “Fine new, fine old, fine barley, old barley, old rye”…they were all descriptions and prices for grain! Newspapers from London describing shipments of grain from America in the early 1800s show the use of these terms constantly. So now…when does the term “old rye” even begin to mean aged rye whiskey? I’m working with Justin Cherry again to learn more about these connections.

It’s that “chicken or the egg” conundrum again. My theory is that “fine old rye whiskey” developed the same way that straight whiskey did. It all started with the grain. Over time, the commodity flour/grain market terms were adopted by the liquor industry as qualitative terms describing the quality of their products. It probably just started as a easy way for salesmen to communicate with buyers that were used to buying commodities and stock for their dry goods store. Eventually, the grain market terms were no longer relevant, but the liquor market continued to use and refine their meanings. That’s my theory anyway…I hope to see what others think.

So was “old” whiskey barrel aged in the early 1800s? All signs point to yes. Perhaps the reason we tend think that whiskey was not aged for years in warehouses is because the government did not establish a bonding period until 1868. It was only a year, but it was established because the distilleries had been taking advantage of a lax warehouse bonding system for decades. The government, which had been losing nearly 2/3 of the taxes they should have been collecting due to numbers manipulation and inadequate storekeepers began keeping more detailed records of the whiskey going into and out of distillery warehouses. Aged rye whiskey had been popular since the early 1800s, but there was a limited supply of it.

In the 1850s, the demand for aged whiskey outpaced its supply, and distillers like John Gibson in Philadelphia began building their own plants to supply themselves. The Civil War era marked an uptick in the production of whiskey specifically catering to a new and growing class of whiskey drinkers. Here’s where we see that need for the development of a “straight” and “pure rye” whiskey category- barrel aged whiskeys that communicated their quality to these consumers.

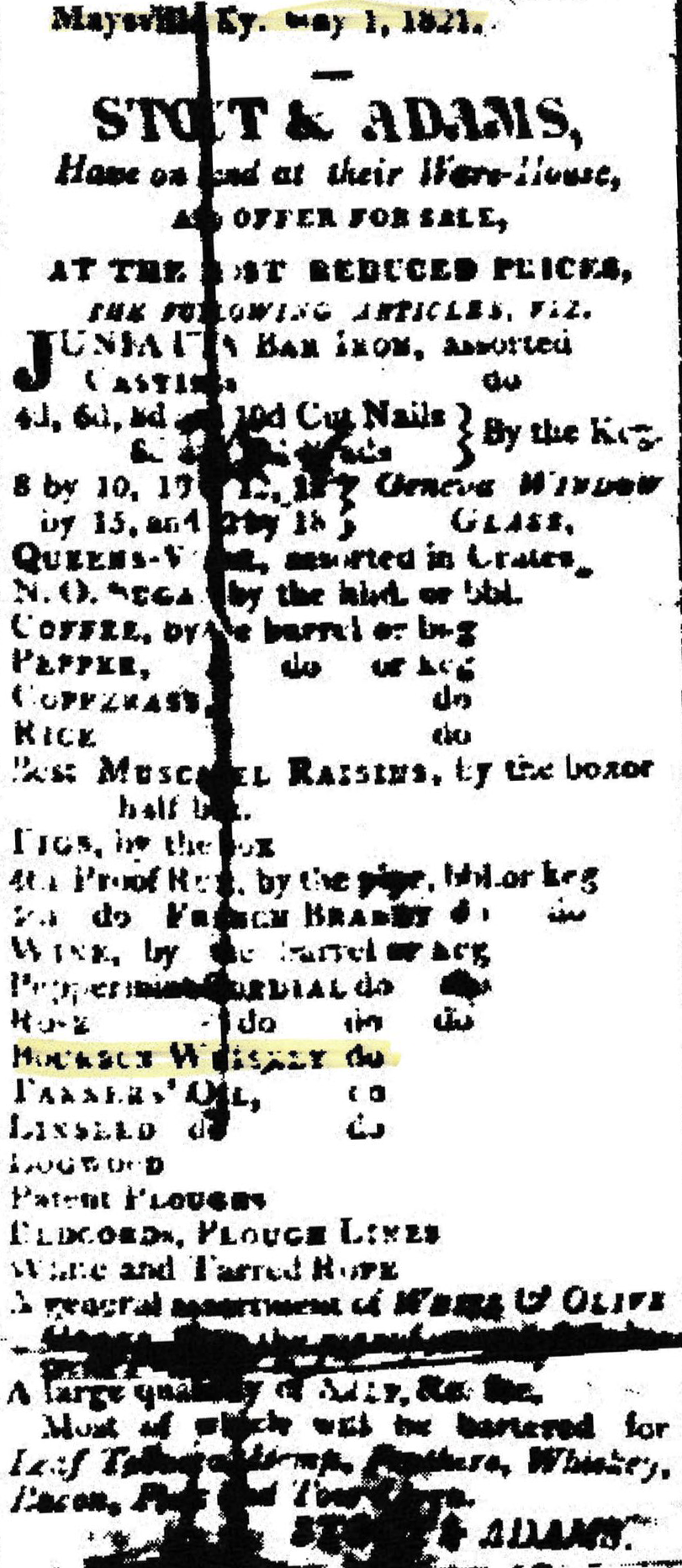

Last but not least- “common whiskey.” This term is no longer used, but it used to refer to a basic corn whiskey distilled to a lower proof. It was a cheaper version of whiskey- usually unaged or very young and was often purchased for use in rectification. This term for whiskey preceded the use of the term “high wines” as the type of white whiskey used by rectifiers. Once re-distilled, high wines would be called neutral or cologne spirits. “Common whiskey” was a term that had been carried over from Europe and had been used since the earliest advertisements of whiskey for sale. The common man drank his common whiskey. As rectification improved with the use of patent column stills in the early 1800s, the use of the term “common whiskey” faded away. Europe was using its Coffey still after 1830 and America was using its own version of a continuous still – column stills. These rectified spirits were distilled to a higher ABV (160-180 proof) while the common whiskey was much lower- likely less than half that amount. It was also known for having a much higher proportion of fusel oils.